The real threat to manhood: remaining children

This is an interesting article that, to be honest, I expected a bit more from. It comments on some obvious things such as how problematic a rigid and joyless form of ultra-masculinity can be, as well as being careful not to say that discipline isn’t important.

While I appreciate that the author, Dave Holmes, doesn’t use the term ‘toxic masculinity’ (which I think doesn’t really mean anything any more) what I do think he could have developed further is the very last line. In it, he mentions that the real threat to manhood is us “staying children” which is a much more interesting area to explore.

The world is more individualised, gamified, and commercialised than ever before. Masculinity, as a concept, is therefore an idea to be bought and sold. The version we need to fix the world is not the version that gains the most likes on social media; it’s one that is confident, self-reflective, and biased towards helping others.

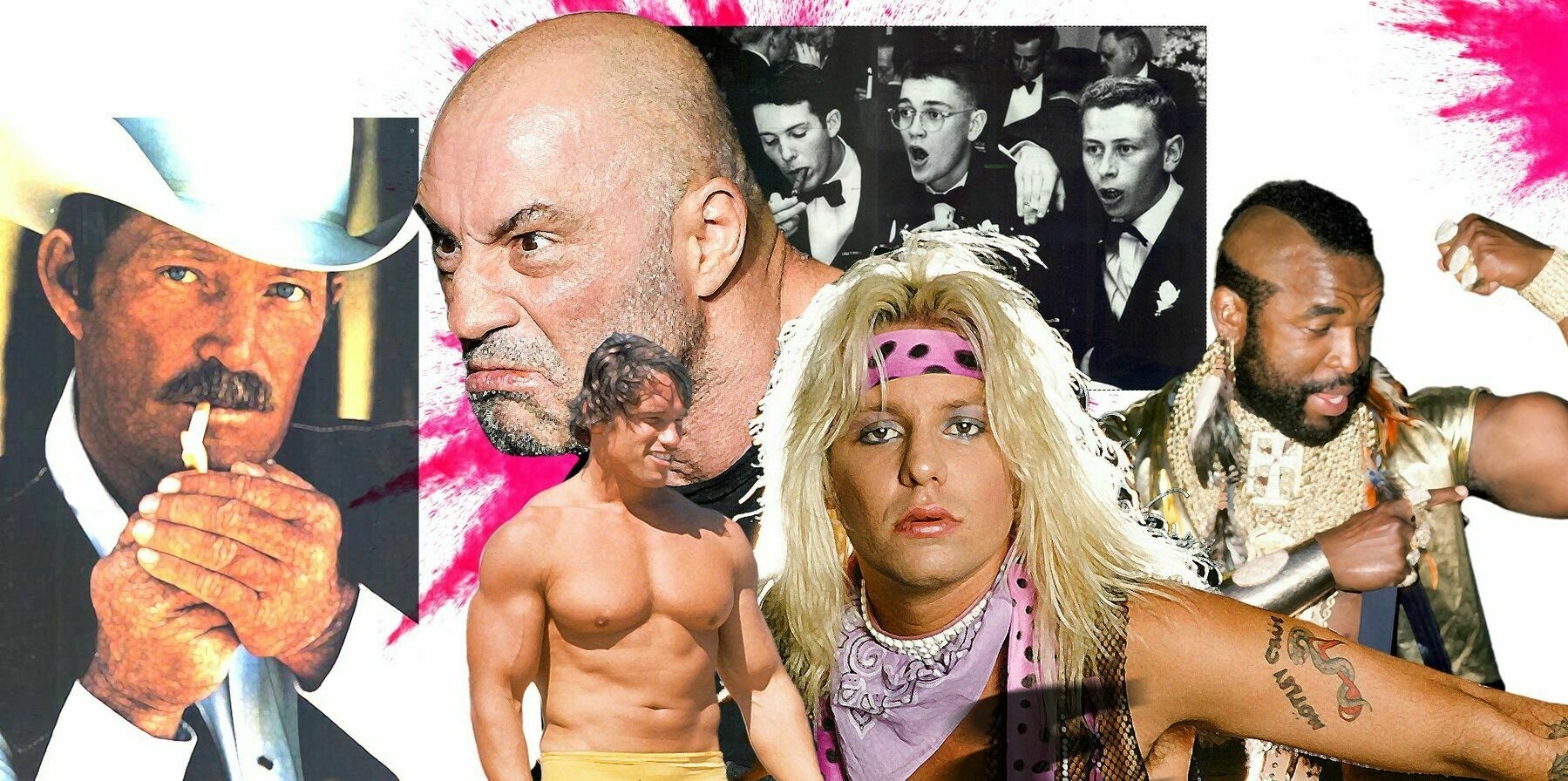

You can be forgiven for not noticing that men aren’t men anymore, because men are always not men anymore. “Men aren’t men anymore”—like “nobody younger than me wants to work” and “this isn’t real music”—has been said every day in every language since we’ve had days and languages. It’s a particular concern in America, where men haven’t been men anymore from the jump. Almost certainly one of our founding fathers told his son, “Don’t leave this house without your wig, stockings, and frock coat—I didn’t raise a sissy.”Source: Can You Still Say ‘Be A Man’? | Esquire[…]

“Men are not men anymore” is ancient; “men are not men anymore, buy this and fix that,” slightly newer. But this is a much bleaker time, a time of “men are not men anymore, smash that subscribe button.” A generation of boys looking for rules has met a generation of creeps looking for an audience: Jordan Peterson, Steven Crowder, Andrew Tate. Guys who offer a rigid and joyless version of masculinity. Guys whose brand says, “I have learned how to throttle everything that is exuberant and playful within myself to become someone else’s version of what a man is; what’s wrong with you?” Guys who have chosen a car for its color and will never forgive themselves for it.

[…]

This is not to say you should throw away rules, or that playing to a person’s insecurity isn’t sometimes the right move. I quit smoking at 30, cold turkey, unless I was in a bar, or walking home after a good meal, or near someone who asked, “Would you like a cigarette?” My friend Lee picked up on this. “For someone who has quit smoking,” he said, “you are doing a lot of smoking.” I protested, “It’s just hard in certain situations.” Lee looked me in the eye and said, “Have you tried being a man?” Haven’t had a cigarette since.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Lee aren’t saying independent thinking and discipline are virtues for men as opposed to women. They are just virtues. Rules for good living. Like we aim to provide in the Esquire of 2023. It’s time we stop being so worried about becoming women and start focusing on the real threat to manhood: staying children.

Actions speak louder than words

This article popped up on my feeds a couple of weeks ago and I recognised the organisation behind the website. Having listened to an excellent Art of Manliness podcast episode featuring Dr John Barry, I knew that ‘The Centre for Male Psychology’ is actually legit.

What this article discusses I’ve found true in my own life. I am by temperament introspective, which means for many years I thought the answer to any form of melancholy came in thinking. But, actually, I’ve found the answer to be in action in doing things such as climbing mountains, running, and doing things with my hands.

The two ways of regulating emotions have implications for the field of mental health, which relies predominately on talking therapy – in particular talking about feelings. Does this not suggest that there could be, and perhaps needs to be, more emphasis on discussing the therapeutic value of action? It may not be practical to conduct therapy while engaged in physical activity such as a gym workout or while out walking in the streets, but the therapeutic discussion can at least focus more on the “doing” aspects of a man’s life. For example a therapist might ask how did problem XYZ make a man act out, along with exploring which physical activities or responses might help him to modulate such emotions more optimally in future. Does riding a Jet Ski, or going for a jog, or building some wooden furniture make him feel better or worse? Does that difficult manoeuvre in the video game remind of difficulties in his relationship with his girlfriend? Does the same video game provide some optimism that if he can get past the difficult manoeuvre within the game then perhaps he can find a way around the impasse with his girlfriend? Activities like these provide a symbolic canvas on which men project, and then work through various scenarios of real life, with potential to shift affective resonances in the process.Source: Men tend to regulate their emotions through actions rather than words | The Centre for Male PsychologyWhen a man talks about how he operated a lathe, did some welding, restored a bit of discarded and broken furniture, might he be sharing a strategy of how he successfully redirected suicidal feelings? Perhaps we should not be so quick to shut down these conversations with accusations of being work obsessed, effectively stymieing natural male expressions with injunctions to talk less about activities and to communicate more effusively with feelings words. For many men, activities are the preferred canvases on which they can process feelings and carve out some genuine psychological equilibrium.

This is probably a reason why men talk so much about work, sports, building things, computer games, recreational activities – it may be their preferred way of communicating the ways they wrestle with psychological issues. Sadly, the therapeutic industry is quick to chastise men’s preference for intelligent actions, conflating them with pathological reflexes such as unconscious acts of aggression, dependence on drugs and booze, and other destructive versions of so-called “acting-out” as they are so often branded.

Everything intercepts us from ourselves

🤝 Medieval English people used to pay their rent in eels

🤺 The Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports Among Ivy League–Obsessed Parents

📜 Archaeologists unearth 'huge number' of sealed Egyptian sarcophagi

🌉 3D model of how the Charles bridge in Prague was constructed

💪 Every Man Should Be Able to Save His Own Life: 5 Fitness Benchmarks a Man Must Master

Quotation by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Image from top-linked post.

Seeing through is rarely seeing into

♂️ What does it mean to be a man in 2020? Introducing our news series on masculinity

✏️ Your writing style is costly (Or, a case for using punctuation in Slack)

Quotation-as-title by Elizabeth Bransco. Image from top-linked post.