-

Community forms based off of a common interest, personality, value set, etc. We’ll describe “people who strongly share the interest/personality/value” as Possums: people who like a specific culture. These people have nothing against anybody, they just only feel a strong sense of community from really particular sorts of people, and tend to actively seek out and form niche or cultivated communities. To them, “friendly and welcoming” community is insufficient to give them a sense of belonging, so they have to actively work to create it. Possums tend to (but not always) be the originators of communities.

-

This community becomes successful and fun

-

Community starts attracting Otters: People who like most cultures. They can find a way to get along with anybody, they don’t have specific standards, they are widely tolerant. They’re mostly ok with whatever sort of community comes their way, as long as it’s friendly and welcoming. These Otters see the Possum community and happily enter, delighted to find all these fine lovely folk and their interesting subculture.(e.g., in a christian chatroom, otters would be atheists who want to discuss religion; in a rationality chatroom, it would be members who don’t practice rationality but like talking with rationalists)

-

Community grows to have more and more Otters, as they invite their friends. Communities tend to acquire Otters faster than Possums, because the selectivity of Possums means that only a few of them will gravitate towards the culture, while nearly any Otter will like it. Gradually the community grows diluted until some Otters start entering who don’t share the Possum goals even a little bit – or even start inviting Possum friends with rival goals. (e.g., members who actively dislike rationality practices in the rationality server).

-

Possums realize the community culture is not what it used to be and not what they wanted, so they try to moderate. The mods might just kick and ban those farthest from community culture, but more frequently they’ll try to dampen the blow and subsequent outrage by using a constitution, laws, and removal process, usually involving voting and way too much discussion.

-

The Otters like each other, and kicking an Otter makes all of the other Otters members really unhappy. There are long debates about whether or not what the Possum moderator did was the Right Thing and whether the laws or constitution are working correctly or whether they should split off and form their own chat room

-

The new chat room is formed, usually by Otters. Some of the members join both chats, but the majority are split, as the aforementioned debates generated a lot of hostility

-

Rinse and repeat—

- Operational support: functions like finance, legal, and HR that help people do their jobs

- Demand: generating customers (through marketing/sales, branding, and relationships)

- Networks: access to communities that support the individual

- Users don't really understand interfaces

- Computers don't really understand users

- Big Data assumes that users are behaving in semi-rational manner

Securing your digital life

Usually, guides to securing your digital life are very introductory and basic. This one from Ars Technica, however, is a bit more advanced. I particularly appreciate the advice to use authenticator apps for 2FA.

Remember, if it’s inconvenient for you it’s probably orders of magnitude more inconvenient for would-be attackers. To get into one of my cryptocurrency accounts, for example, I’ve set it so I need a password and three other forms of authentication.

Overkill? Probably. But it dramatically reduces the likelihood that someone else will make off with my meme stocks…

Security measures vary. I discovered after my Twitter experience that setting up 2FA wasn’t enough to protect my account—there’s another setting called “password protection” that prevents password change requests without authentication through email. Sending a request to reset my password and change the email account associated with it disabled my 2FA and reset the password. Fortunately, the account was frozen after multiple reset requests, and the attacker couldn’t gain control.Source: Securing your digital life, part two: The bigger picture—and special circumstances | Ars TechnicaThis is an example of a situation where “normal” risk mitigation measures don’t stack up. In this case, I was targeted because I had a verified account. You don’t necessarily have to be a celebrity to be targeted by an attacker (I certainly don’t think of myself as one)—you just need to have some information leaked that makes you a tempting target.

For example, earlier I mentioned that 2FA based on text messages is easier to bypass than app-based 2FA. One targeted scam we see frequently in the security world is SIM cloning—where an attacker convinces a mobile provider to send a new SIM card for an existing phone number and uses the new SIM to hijack the number. If you’re using SMS-based 2FA, a quick clone of your mobile number means that an attacker now receives all your two-factor codes.

Additionally, weaknesses in the way SMS messages are routed have been used in the past to send them to places they shouldn’t go. Until earlier this year, some services could hijack text messages, and all that was required was the destination phone number and $16. And there are still flaws in Signaling System 7 (SS7), a key telephone network protocol, that can result in text message rerouting if abused.

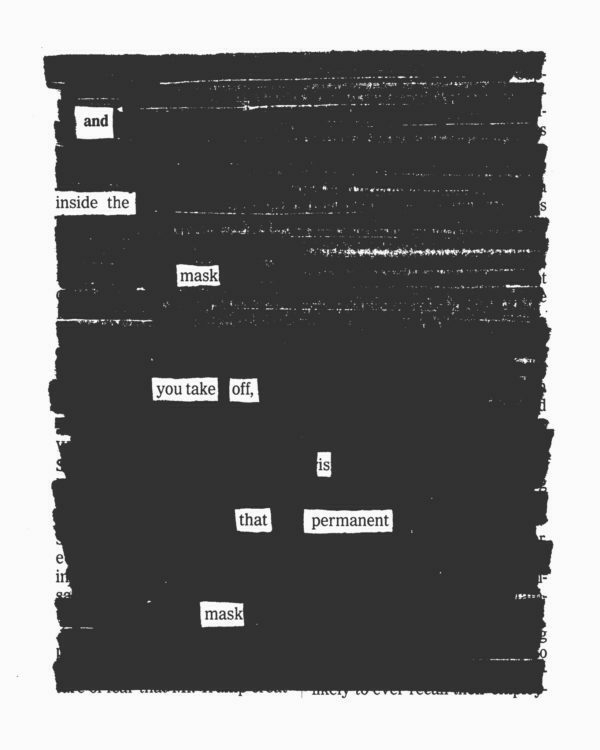

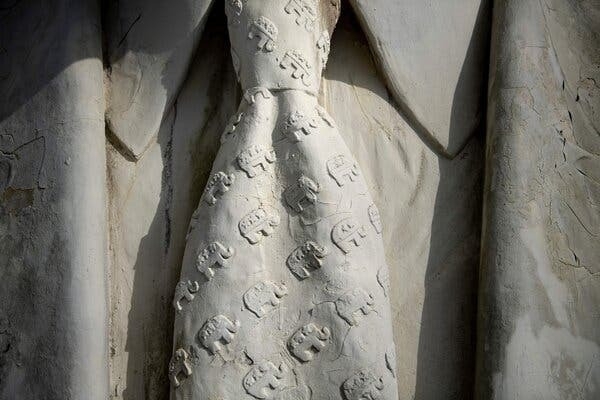

The permanent mask

I’m sharing this mainly for the blackout poetry, but I also appreciate the quotation from Nabakov that Austin Kleon shares in this post.

As I explained in my checking out of therapy post, you can “paint yourself into a rather unhelpful corner by being the person everyone else expects you to be”. Taking off that mask can be liberating.

I don’t think that an artist should bother about his audience. His best audience is the person he sees in his shaving mirror every morning. I think that the audience an artist imagines, when he imagines that kind of a thing, is a room filled with people wearing his own mask.Source: Inside the mask | Austin Kleon

Psychological hibernation

I can’t really remember what life was like before having children. Becoming a parent changes you in ways you can’t describe to non-parents.

Similarly, if we tried to go back in time and explain how the pandemic has changed us, how we’re more susceptible to burnout, less up for meeting with other people, it would be almost impossible to do.

One term that might be useful, however, is ‘psychological hibernation’ — as this article explains.

Was it always like this? Can anyone actually remember what it was like before? For some reason, coming up with an answer to that question is like recalling a boring dream: the more you attempt to remember the details of life before Covid, the quicker it fades, as if it never happened at all.Source: The great Covid social burnout: why are we so exhausted? | New StatesmanIn 2018, a group of psychologists in the Antarctic published a report that may help us understand our current collective exhaustion. The researchers found that the emotional capacity of people who had relocated to the end of the world had been significantly reduced in the time they had been there; participants living in the Antarctic reported feeling duller than usual and less lively. They called this condition “psychological hibernation”. And it’s something many of us will be able to relate to now.

“One of the things that we noticed throughout the pandemic is that people started to enter this phase of psychological hibernation,” said Emma Kavanagh, a psychologist specialising in how people deal with the aftermath of disasters. “Where there’s not many sounds or people or different experiences, it doesn’t require the brain to work at quite the same level. So what you find is that people felt emotionally like everything had just been dialled back. It looks a lot like burnout, symptom wise.” Kavanagh continued: “I think that happened to us all in lockdown, and we are now struggling to adapt to higher levels of stimulus.”

Otters vs. Possums

It’s an odd metaphor, but the behaviours described in terms of internet communities are definitely something I’ve witnessed in 25 years of being online.

(This post is from 2017 but popped up on Hacker News recently.)

There’s a pattern that inevitably emerges, something like this:Source: Internet communities: Otters vs. Possums | knowingless

What are microcredentials?

I suppose we should have listened when people told the team I was on at Mozilla time and time again that the name ‘Open Badges’ didn’t work for them. They didn’t seem to get the fact that they could call them anything they liked in their organisations; the important thing was that they aligned with the open standard.

A decade later, and ‘microcredentials’ seems to be one term that’s been adopted, especially towards the formal end of the credentialing spectrum. In this interview, Jackie Pichette, Director of Research and Policy for the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, takes a Higher Education-centric look at the landscape.

I may be cynical, but it comes across a lot like “that’s all very well in practice, but what about in theory?"

There’s a lot of confusion around the definition of the microcredential. When my colleagues and I started our research in February 2020, just before the world turned upside down, one of our aims was to help establish some common understanding. We engaged experts and consulted literature from around the world to help us answer questions like, What constitutes a microcredential? How is a microcredential different from a digital badge or a certificate?Source: How Do Microcredentials Stack Up? Part 1 | The EvoLLLutionWe landed on an umbrella definition of programs focused on a discrete set of competencies (i.e., skills, knowledge, attributes) that, by virtue of having a narrow focus, require less time to obtain than traditional credentials. We also came up with a typology to show the variation in this definition. For example, microcredentials can be self-paced to accommodate individual schedules, can follow a defined schedule or feature a mix of fixed- and self-paced elements.

Walking the Covid tightrope

I’m sharing this article mainly for the genius of the accompanying illustration, although it also does a good job of trying to explain an increasing feeling of English exceptionalism.

The results look increasingly alarming. In pubs, in shops, on public transport and in other enclosed spaces where the virus easily spreads, many people are acting as if the pandemic is over – or at least, over for them. Mask-wearing and social distancing have sometimes become so rare that to practise them feels embarrassing.Source: With Covid infections rising, the Tories are conducting a deadly social experiment | The GuardianMeanwhile, England has become one of the worst places for infections in the world, despite a high degree of vaccination by global standards. Case numbers, hospitalisations and deaths are all rising, and are already much higher than in other western European countries that have kept measures such as indoor mask-wearing compulsory, and where compliance with such rules has remained strong. What does England’s failure to control the virus through “personal responsibility” say about our society?

It’s tempting to start by generalising about national character, and how the supposed individualism of the English has become selfishness after half a century of frequent rightwing government and fragmentation in our lives and culture. There may be some truth in that. But national character is not a very solid concept, weakened by all the differences within countries and all the similarities that span continents. Thanks to globalisation, all European societies have been affected by the same atomising forces. England’s lack of altruism during the pandemic can’t just be blamed on neoliberalism.

Other elements of our recent history may also explain it. England likes to think of itself as a stable country, yet since the 2008 financial crisis it has endured a more protracted period of economic, social and political turmoil than most European countries. The desire to return to some kind of normality may be especially strong here; taking proper anti-Covid precautions would be an acknowledgement that we cannot do that.

Kith and kin

This is a great article about how the internet was going to save us from TV and now we’re looking for something to save us from the internet. What we actually need are stronger and deeper relationships with the people around us — our kith and kin.

We are conditioned to care about kin, to take life’s meaning from the relationships with those we know and love. But the psychological experience of fame, like a virus invading a cell, takes all of the mechanisms for human relations and puts them to work seeking more fame. In fact, this fundamental paradox—the pursuit through fame of a thing that fame cannot provide—is more or less the story of Donald Trump’s life: wanting recognition, instead getting attention, and then becoming addicted to attention itself, because he can’t quite understand the difference, even though deep in his psyche there’s a howling vortex that fame can never fill.Source: On the Internet, We’re Always Famous | The New YorkerThis is why famous people as a rule are obsessed with what people say about them and stew and rage and rant about it. I can tell you that a thousand kind words from strangers will bounce off you, while a single harsh criticism will linger. And, if you pay attention, you’ll find all kinds of people—but particularly, quite often, famous people—having public fits on social media, at any time of the day or night. You might find Kevin Durant, one of the greatest basketball players on the planet, possibly in the history of the game—a multimillionaire who is better at the thing he does than almost any other person will ever be at anything—in the D.M.s of some twenty something fan who’s talking trash about his free-agency decisions. Not just once—routinely! And he’s not the only one at all.

There’s no reason, really, for anyone to care about the inner turmoil of the famous. But I’ve come to believe that, in the Internet age, the psychologically destabilizing experience of fame is coming for everyone. Everyone is losing their minds online because the combination of mass fame and mass surveillance increasingly channels our most basic impulses—toward loving and being loved, caring for and being cared for, getting the people we know to laugh at our jokes—into the project of impressing strangers, a project that cannot, by definition, sate our desires but feels close enough to real human connection that we cannot but pursue it in ever more compulsive ways.

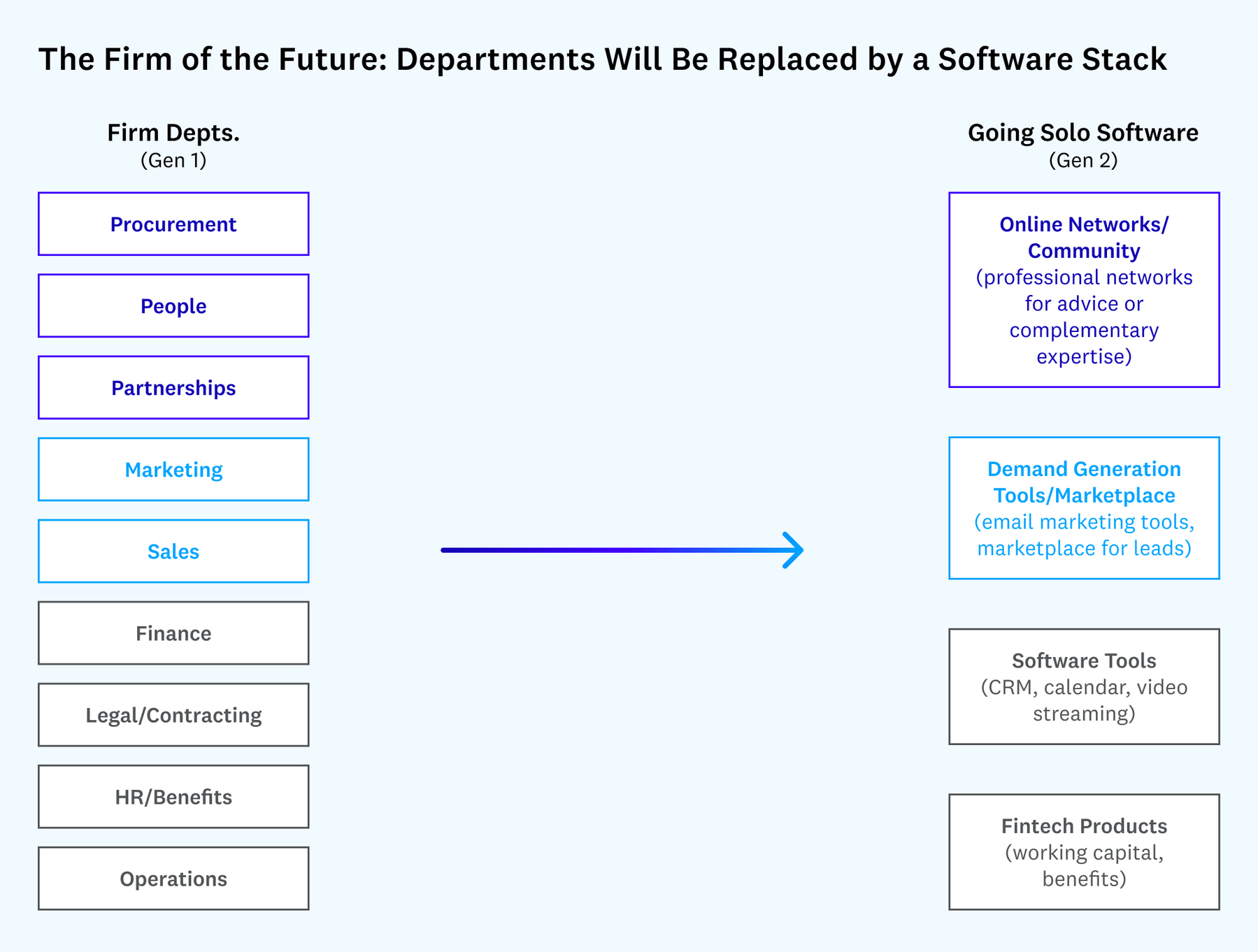

Bring Your Own Stack

Venture Capitalists inhabit a slightly different world than the rest of us. This post, for example, paints a picture of a future that makes sense to people deeply enmeshed in Fintech, but not for those of us outside of that bubble.

That being said, there’s a nugget of truth in there about the need for more specific services for particular sectors, rather than relying on generic ones provides by Big Tech.

However, the chances are that those will simply plug in to existing marketplaces (e.g. Google Workplace) rather than strike out on their own. But, what do I know?

There’s a pressing need — and an opportunity — to build vertical-specific tools for workers striking out on their own. Much has been written about the proliferation of vertical software tools that help firms run their businesses, but the next generation of great companies will provide integrated, vertical software for individuals going solo.Source: As More Workers Go Solo, the Software Stack Is the New Firm | FutureSolo workers venturing out on their own need to feel like they can replace the support of a company model. Traditionally, the firm brings three things to support the core craft or product:

The solo stacks of the future will offer a mix of these three things (depending on what makes sense for any industry), giving workers the tools — and thus, the confidence — to leave their jobs. The software will be vertical-specific, as well, as lawyers, personal trainers, money managers, and graphic designers all need different tools, have different customers to market to, and require access to different networks to do their jobs.

Fall Regression

I’ve only just discovered the writing of Anne Helen Petersen, via one of the many newsletters and feeds to which I subscribe. I featured her work last week about remote working.

Petersen’s newsletter is called Culture Study and the issue that went out yesterday was incredible. She talks about this time of year — a time I struggle with in particular — and gets right to the heart of the issue.

I’ve learned to take Vitamin D, turn on my SAD light, and to go easy on myself. But there’s always a little voice suggesting that this is how it’s going to be from here on out. So it’s good to hear what other people advise. For Petersen, it’s community involvement.

A teacher recently told me that there’s a rule in her department: no major life decisions in October. The same holds true, she said, for March. But March is well-known for its cruelty. I didn’t realize it was the same for October, even though it makes perfect sense: the charge of September, those first golden days of Fall, the thrill of wearing sweaters for the first time, those are gone. Soon it’ll be Daylight Savings, which always feels like having the wind knocked out of the day. People in high elevations are already showing off their first blasts of snow. We have months, months, to go.Source: What’s That Feeling? Oh, It’s Fall Regression | Culture StudyAs distractions fade, you’re forced to sit with your own story of how things are going. Maybe you’d been bullshitting yourself for weeks, for months. It was easy to ignore my bad lunch habits when I was spending most of the day outside. Now it’s just me and my angry stomach and scraping the tub of the hummus container yet again. Or, more seriously: now it’s just me swimming against the familiar tide of burnout, not realizing how far it had already pulled me from shore.

[…]

Is this the part of the pandemic when we’re happy? When we’re angry? When we’re hanging out or pulling back, when we’re hopeful or dismayed, when we’re making plans or canceling them? The calendar moves forward but we’re stuck. In old patterns, in old understandings of how work and our families and the world should be. That’s the feeling of regression, I think. It’s not that we’re losing ground. It’s that we were too hopeful about having gained it.

Reducing long-distance travel

I agree with what Simon Jenkins is saying here about focusing on the ‘reduce’ part of sustainable travel. However, it does sound a bit like victim-blaming to say that people outside of London travel mainly by car.

We travel primarily by car because of the lack of other options. Infrastructure is important, including outside of our capital city.

It is an uncomfortable fact that most people outside London do most of their motorised travel by car. The answer to CO2 emissions is not to shift passengers from one mode of transport to another. It is to attack demand head on by discouraging casual hyper-mobility. The external cost of such mobility to society and the climate is the real challenge. It cannot make sense to predict demand for transport and then supply its delivery. We must slowly move towards limiting it.Source: Train or plane? The climate crisis is forcing us to rethink all long-distance travel | The GuardianOne constructive outcome of the Covid pandemic has been to radically revise the concept of a “journey to work”. Current predictions are that “hybrid” home-working may rise by as much as 20%, with consequent cuts in commuting travel. Rail use this month remains stubbornly at just 65% of its pre-lockdown level. Office blocks in city centres are still half-empty. Covid plus the digital revolution have at last liberated the rigid geography of labour.

Climate-sensitive transport policy should capitalise on this change. It should not pander to distance travel in any mode but discourage it. Fuel taxes are good. Road pricing is good. So are home-working, Zoom-meeting (however ghastly for some), staycationing, local high-street shopping, protecting local amenities and guarding all forms of communal activity.

Time millionaires

Same idea, new name: there’s nothing new about the idea of prioritising the amount of time and agency you have over the amount of money you make.

It’s just that, after the pandemic, more people have realised that chasing money is a fool’s errand. So, whatever you call it, putting your own wellbeing before the treadmill of work and career is always a smart move.

First named by the writer Nilanjana Roy in a 2016 column in the Financial Times, time millionaires measure their worth not in terms of financial capital, but according to the seconds, minutes and hours they claw back from employment for leisure and recreation. “Wealth can bring comfort and security in its wake,” says Roy. “But I wish we were taught to place as high a value on our time as we do on our bank accounts – because how you spend your hours and your days is how you spend your life.”Source: Time millionaires: meet the people pursuing the pleasure of leisure | The GuardianAnd the pandemic has created a new cohort of time millionaires. The UK and the US are currently in the grip of a workforce crisis. One recent survey found that more than 56% of unemployed people were not actively looking for a new job. Data from the Office for National Statistics shows that many people are not returning to their pre-pandemic jobs, or if they are, they are requesting to work from home, clawing back all those hours previously lost to commuting.

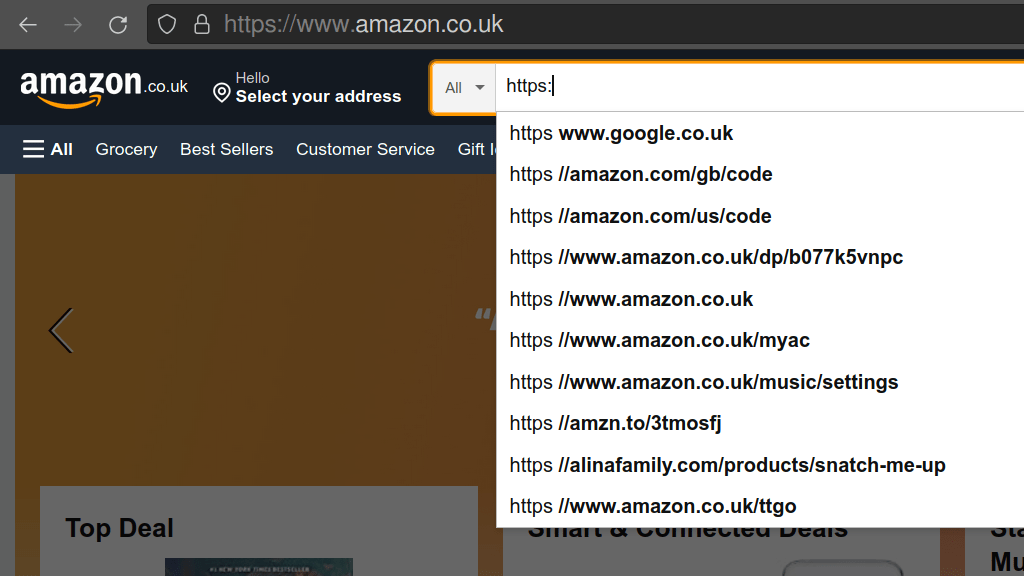

On the digital literacies of regular web users

Terence Eden opened a new private browsing window and started typing “https…” and received the results of lots of different sites.

He uses this to surmise, and I think he’s probably correct, that users conflate search bars and address bars. Why shouldn’t they? They’ve been one and the same thing in browsers for years now.

Perhaps more worrying is that there’s a whole generation of students who don’t know what a file system structure is…

There are a few lessons to take away from this.Source: Every search bar looks like a URL bar to users | Terence Eden’s Blog

Leisure is what we do for its own sake. It serves no higher end.

Yes, yes, and yes. I agree wholeheartedly with this view that places human flourishing above work.

To limit work’s negative moral effects on people, we should set harder limits on working hours. Dr. Weeks calls for a six-hour work day with no pay reduction. And we who demand labor from others ought to expect a bit less of people whose jobs grind them down.Source: Returning to the Office and the Future of Work | The New York TimesIn recent years, the public has become more aware of conditions in warehouses and the gig economy. Yet we have relied on inventory pickers and delivery drivers ever more during the pandemic. Maybe compassion can lead us to realize we don’t need instant delivery of everything and that workers bear the often-invisible cost of our cheap meat and oil.

The vision of less work must also encompass more leisure. For a time the pandemic took away countless activities, from dinner parties and concerts to in-person civic meetings and religious worship. Once they can be enjoyed safely, we ought to reclaim them as what life is primarily about, where we are fully ourselves and aspire to transcendence.

Leisure is what we do for its own sake. It serves no higher end.

UK government adviser warns against plans to force the NHS to share data with police forces

It’s entirely unsurprising that governments should seek to use the pandemic as cover for hoovering up data about its citizens. However, it’s up to us to resist this.

Plans to force the NHS to share confidential data with police forces across England are “very problematic” and could see patients giving false information to doctors, the government’s data watchdog has warned.Source: Plans to hand over NHS data to police sparks warning from government adviser | The Independent[…]

Dr Nicola Byrne also warned that emergency powers brought in to allow the sharing of data to help tackle the spread of Covid-19 could not run on indefinitely after they were extended to March 2022.

Dr Byrne, 46, who has had a 20-year career in mental health, also warned against the lack of regulation over the way companies were collecting, storing and sharing patient data via health apps.

She told The Independent she had raised concerns with the government over clauses in the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill which is going through the House of Lords later this month.

The legislation could impose a duty on NHS bodies to disclose private patient data to police to prevent serious violence and crucially sets aside a duty of confidentiality on clinicians collecting information when providing care.

Dr Byrne said doing so could “erode trust and confidence, and deter people from sharing information and even from presenting for clinical care”.

She added that it was not clear what exact information would be covered by the bill: “The case isn’t made as to why that is necessary. These things need to be debated openly and in public.”

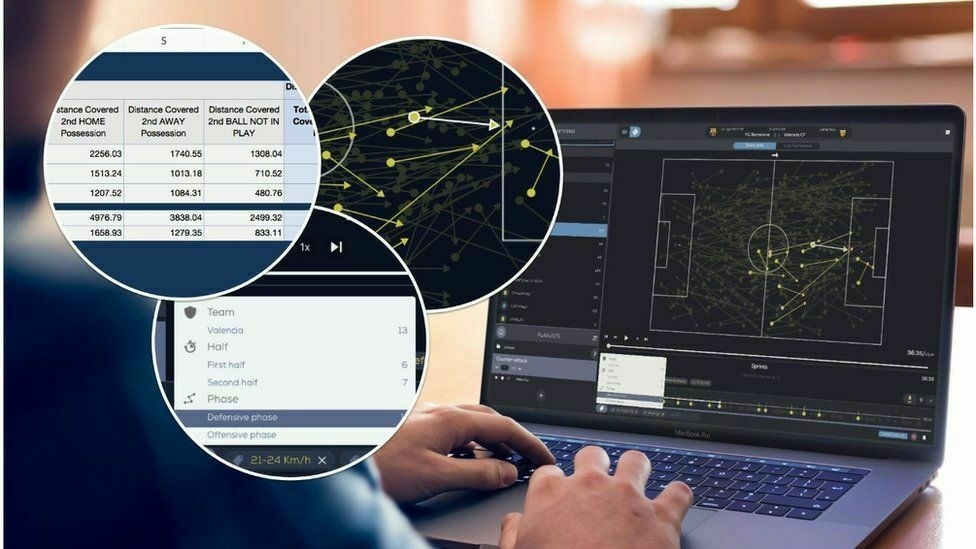

Sports data and GDPR

This is really quite fascinating. The use of player data has absolutely exploded in the last decade, and that's now being challenged from a GDPR (i.e. data privacy) point of view.

Some of it could be said to be reasonably innocuous, but when we get into the territory of players being compared against 'expected goals' things start to get tricky, I'd suggest.

Slade's legal team said the fact players receive no payment for the unlicensed use of their data contravenes General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) rules that were strengthened in 2018.

Under Article 4 of the GDPR, "personal data" refers to a range or identifiable information, such as physical attributes, location data or physiological information.

BBC News understands that an initial 17 major betting, entertainment and data collection firms have been targeted, but Slade's Global Sports Data and Technology Group has highlighted more than 150 targets it believes have misused data.

[...]

Former Wales international Dave Edwards, one the players behind the move, said it was a chance for players to take more control of the way information about them is used.

Having seen how data has become a staple part of the modern game, he believes players rights to how information about them is used should be at the forefront of any future use.

"The more I've looked into it and you see how our data is used, the amount of channels its passed through, all the different organisations which use it, I feel as a player we should have a say on who is allowed to use it," he said.

Source: Footballers demand compensation over 'data misuse' | BBC News

Precrastinators, procrastinators, and originals

A really handy TED talk focusing on ‘precrastinators’ (with whom I definitely identify) and how they differ from procrastinators and what Grant calls ‘originals’ in terms of creativity.

(I always watch these kinds of things at 1.5x speed, but Adam Grant already talks quickly!)

[embed]www.youtube.com/watch

Source: The surprising habits of original thinkers | Adam Grant

Why commute to an office to work remotely?

This piece by Anne Helen Petersen is so good about the return to work. It’s ostensibly about US universities, but is so much widely applicable.

As I’ve said to several people over the past few weeks, the idea of needing staff to be in a physical office most of the time for ‘serendipitous interactions’ is ridiculous. Working openly allows for much greater serendipity surface than any forced physical co-location might achieve.

On college campuses across the United States, staff are back in the office. More specifically, they’re back in their own, individual offices, with their doors closed, meeting with one another over Zoom or Teams, battling low internet speeds, and reminding each other to mute themselves so that the sound of the meeting doesn’t create a deafening echo effect for everyone else.Source: The Worst of Both Work Worlds | Culture StudyFor some, the office is just a quick walk or bike ride away. But for many, coming into the office requires a distinctly unromantic commute. It means cobbling together childcare plans, particularly with the nationwide bus driver shortages and school quarantine regulations after illness or a potential exposure. It means paying for parking, and packing or paying for their lunches, and handing over anywhere from 20 minutes to two hours of their day. They are enduring the worst parts of a “traditional” job, only to go into the office and essentially work remote, with worse conditions and fewer amenities (and, in many cases, less comfort) than they had at home. It’s the worst of both work worlds.

[…]

The university might seem like a weird example of an “office,” but it’s a pretty vivid illustration of one. You have leadership who are obsessed with image, cost cutting, and often deeply out of touch with the day-to-day operations of the organization (administration); a group of “creatives” (tenured faculty) who form the outward core of the organization and thus have significant self-import but dwindling power; full-time employees of various levels who are fundamental to the operation of the organization and chronically under-appreciated (staff) ; an underclass of contingent and contract workers who perform similar jobs to full-time employees but for less pay, fewer protections, less job security, and are held in far less esteem (grad students, adjuncts, and sub-contracted staff, including building, maintenance, food service, security). And then there’s the all-important customer, whose imagined needs, preferences, whims, demands, and supply of capital serve are the axis around which the rest of the organization rotates (students and their parents).

On 'sportswashing'

There has been a lot written and recorded already about Newcastle United, my geographically-closest Premier League football team, and the rival of the team I actually support (Sunderland).

I am certainly sympathetic to the idea that individual people should live their values. But there has to be a line drawn somewhere. For example, I really like the music of the artist Morrissey, yet I think some of his politics and other views are distasteful and problematic.

Likewise, when the sovereign wealth fund of a foreign power provides your football team with untold riches, why shouldn’t you celebrate? While I’d love to live in a world where fans own football clubs (see AFC Wimbledon) as the article points out, this purchase needs to be placed in a wider narrative around Brexit and widening inequalities in society.

You might expect that this would be controversial in Newcastle. This is not any old country buying an English soccer club. It is a country run by the man the United States concluded to have ordered the dismembering of a journalist, a country conducting a brutal war in Yemen that is among the most barbarous in the world.Source: Britain’s Distasteful Soccer Sellout | The AtlanticAnd yet, few in Newcastle seem to care. I mean, why should they? Their rivals in the English Premier League are already owned by some pretty unpleasant regimes or people: Manchester City is controlled by Abu Dhabi, and Chelsea by a Russian oligarch with ties to the Kremlin. What’s the point in turning down someone’s money if nobody else is? The fixer who facilitated the Saudi takeover has, incredibly, insisted that the Saudi state was not taking over Newcastle’s soccer club, but rather its sovereign wealth fund, which, the fixer said, genuinely cared about human rights. Both, of course, are run by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Beyond this cynical piece of performance art, however, the Newcastle United sale is emblematic of something far more fundamental and depressing about the state of Britain.