- Netflix Saves Our Kids From Up To 400 Hours of Commercials a Year (Local Babysitter) — "We calculated a series of numbers related to standard television homes, compared them to Netflix-only homes and found an interesting trend with regard to how many commercials a streaming-only household can save their children from having to watch."

- The Emotional Charge of What We Throw Away (Kottke.org) — "consumers actually care more about how their stuff is discarded, than how it is manufactured"

- Sidewalk Labs' street signs alert people to data collection in use (Engadget) — "The idea behind Sidewalk Labs' icons is pretty simple. The company wants to create an image-based language that can quickly convey information to people the same way that street and traffic signs do. Icons on the signs would show if cameras or other devices are capturing video, images, audio or other information."

- The vision of the home as a tranquil respite from labour is a patriarchal fantasy (Dezeen) — "[F]or a growing number of critics, the nuclear house is a deterministic form of architecture which stifles individual and collective potential. Designed to enforce a particular social structure, nuclear housing hardwires divisions in labour, gender and class into the built fabric of our cities. Is there now a case for architects to take a stand against nuclear housing?

- The Anarchists Who Took the Commuter Train (Longreads) — "In the twenty-first century, the word “anarchism” evokes images of masked antifa facing off against neo-Nazis. What it meant in the early twentieth century was different, and not easily defined. "

- Teens 'not damaged by screen time', study finds (BBC Technology) — "The analysis is robust and suggests an overall population effect too small to warrant consideration as a public health problem. They also question the widely held belief that screens before bedtime are especially bad for mental health."

- Human Contact Is Now a Luxury Good (The New York Times) — "The rich have grown afraid of screens. They want their children to play with blocks, and tech-free private schools are booming. Humans are more expensive, and rich people are willing and able to pay for them. Conspicuous human interaction — living without a phone for a day, quitting social networks and not answering email — has become a status symbol."

- NHS sleep programme ‘life changing’ for 800 Sheffield children each year (The Guardian) — "Families struggling with children’s seriously disrupted sleep have seen major improvements by deploying consistent bedtimes, banning sugary drinks in the evening and removing toys and electronics from bedrooms."

- The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education (Highline) — "As our most trusted universities continue to privatize large swaths of their academic programs, their fundamental nature will be changed in ways that are hard to reverse. The race for profits will grow more heated, and the social goal of higher education will seem even more like an abstraction."

- Social Peacocking and the Shadow (Caterina Fake) — "Social peacocking is life on the internet without the shadow. It is an incomplete representation of a life, a half of a person, a fraction of the wholeness of a human being."

- Why and How Capitalism needs to be reformed (Economic Principles) — "The problem is that capitalists typically don’t know how to divide the pie well and socialists typically don’t know how to grow it well."

- While some children took part in organised after school clubs at least about one a week, not many of them did other or more spontaneous activities (e.g. physically meeting friends or cultivating hobbies) on a regular basis

- Many children used social media and other messaging platforms (e.g. chat functions in games) to continually keep in touch with their friends while at home

- Often children described going out to meet friends face-to-face as ‘too much effort’ and preferred to spend their free time on their own at home

- While some children managed to fit screen time around other offline interests and passions, for many, watching videos was one of the main activities taking up their spare time

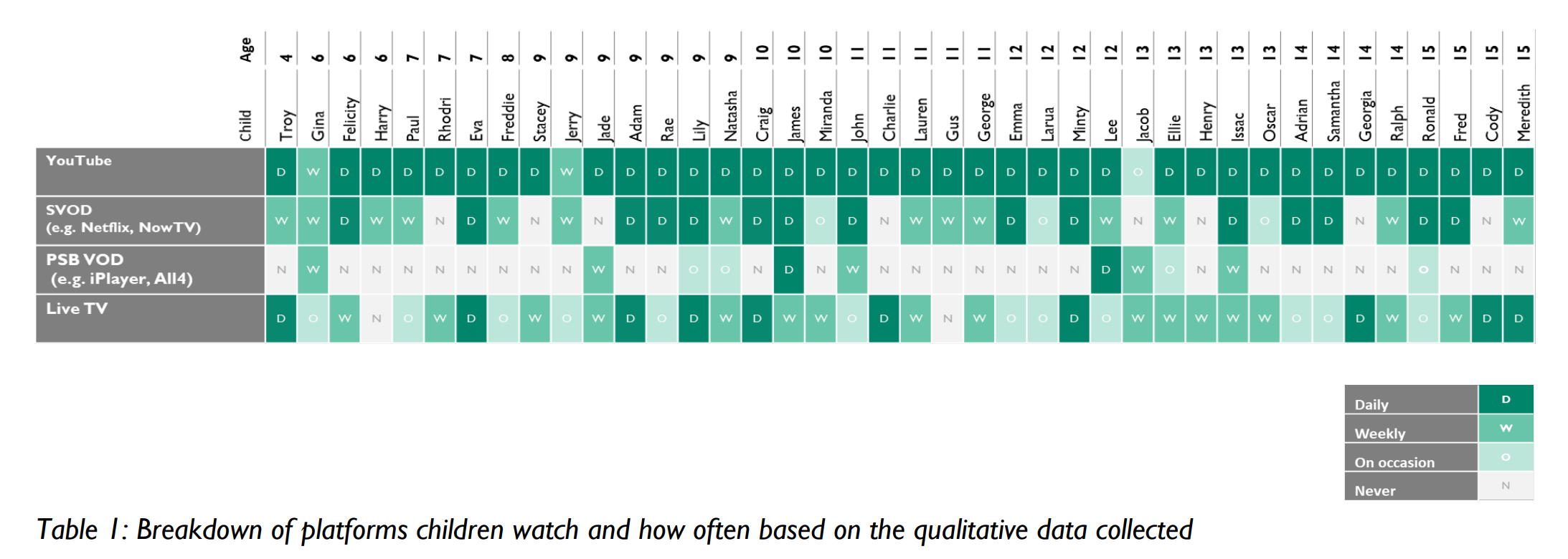

- YouTube was the most popular platform for children to consume video content, followed by Netflix. Although still present in many children’s lives, Public Service Broadcasters Video On Demand] platforms and live TV were used more rarely and seen as less relevant to children like them

- Many parents had attempted to enforce rules about online video watching, especially with younger children. They worried that they could not effectively monitor it, as opposed to live or on-demand TV, which was usually watched on the main TV. Some were frustrated by the amount of time children were spending on personal screens.

- The appeal of YouTube also appeared rooted in the characteristics of specific genres of content.

- Some children who watched YouTubers and vloggers seemed to feel a sense of connection with them, especially when they believed that they had something in common

- Many children liked “satisfying” videos which simulated sensory experiences

- Many consumed videos that allowed them to expand on their interests; sometimes in conjunction to doing activities themselves, but sometimes only pursuing them by watching YouTube videos

- These historically ‘offline’ experiences were part of YouTube’s attraction, potentially in contrast to the needs fulfilled by traditional TV.

- Can I play on your phone until you wake up?

- Can we listen to bouncy music instead of this podcast about the Mueller investigation while we make breakfast?

- Will you pre-chew my gumball since it is too large to fit in my mouth?

- Will you tell us who you are texting?

- Do you want to eat the meat out the tail of this shrimp?

- If children are asking a lot of permission-related questions, then it's worth your while to help them understand what's allowed and what's not allowed. Allow them to help themselves more than they do currently.

- If children are complaining about equality and they're different ages, explain to both of them that you treat them equitably but not eqully. When they complain that's not fair, send the older one to bed at the same time as the younger one (and perhaps give them the same amount of pocket money), and get the younger one to help more around the house. They don't stop complaining, but they certainly do it less...

- Allow children to preview the game on YouTube, if available.

- Provide children with time to readjust to the real world after playing, and give them a break before engaging with activities like crossing roads, climbing stairs or riding bikes, to ensure that balance is restored.

- Check on the child’s physical and emotional wellbeing after they play.

Cosplaying adulthood

I discovered this article published at The Cut while browsing Hacker News. I was immediately drawn to it, because one of the main examples it uses is ‘cosplaying’ adulthood while at kids' sporting events.

There’s a few things to say about this, in my experience. The first is that status tends to be conferred by how good your kid is, no matter what your personality. Over and above that, personal traits — such as how funny you are — make a difference, as does how committed and logistically organised you are. And if you can’t manage that, you can always display appropriate wealth (sports kit, the car you drive). Crack all of this, and congrats! You’ve performed adulthood well.

I’m only being slightly facetious. The reason I can crack a wry smile is because it’s true, but also I don’t care that much because I’ve been through therapy. Knowing that it’s all a performance is very different to acting like any of it is important.

It’s impressive how much parents’ beliefs can seep in, especially the weird ones. As an adult, I’ve found myself often feeling out of place around my fellow parents, because parenthood, as it turns out, is a social environment where people usually want to model conventional behavior. While feeling like an interloper among the grown-ups might have felt hip and righteous in my dad’s day, it makes me feel like a tool. It does not make me feel like a “cool mom.” In the privacy of my own home, I’ve got plenty of competence, but once I’m around other parents — in particular, ones who have a take-charge attitude — I often feel as inept as a wayward teen.Source: Adulthood Is a Mirage | The CutThe places I most reliably feel this way include: my kids’ sporting events (the other parents all seem to know each other, and they have such good sideline setups, whereas I am always sitting cross-legged on the ground absentmindedly offering my children water out of an old Sodastream bottle and toting their gear in a filthy, too-small canvas tote), parent-teacher meetings, and picking up my kids from their friends’ suburban houses with finished basements.

I’ve always assumed this was a problem unique to people who came from unconventional families, who never learned the finer points of blending in. But I’m beginning to wonder if everyone feels this way and that “the straight world,” or adulthood, as we call it nowadays, is in fact a total mirage. If we’re all cosplaying adulthood, who and where are the real adults?

Yes, parenting matters

Parenting is the hardest job I have ever had. It never stops, and I seldom think I’m doing a good job at it.

That’s why it can be comforting to see ‘scientific studies’ indicate that it doesn’t really matter how you parent, in the long-run. The trouble is, as this article shows, that’s not actually true.

We can’t experimentally reassign children to different parents — we’re not monsters, and please don’t call to offer us your teenager — but sometimes real life does that anyway. Here’s an example: some Korean adoptees were assigned to American adopters by a queueing system which was essentially random. So there was no correlation between adoptees’ and parents’ genes. Yet, adoptees assigned to better educated families became significantly better educated themselves. Adopters made a difference in other ways too: for instance, mothers who drank were about 20% more likely to have an adoptive child who drank. This can’t be genetics. It must be something about the environment these parents provided. Other adoption studies reach similar conclusions.Source: No wait stop it matters how you raise your kids | Wyclif’s DustMore evidence comes from the grim events of death and divorce. If your parent dies while you are very young, you end up less like that parent, in terms of education, than otherwise. Again, that can’t be genetics. And children of parents who divorce become more like the parent they stay with. In other words, when parents spend time with their children, their behaviours and values rub off.

[…]

The bottom line is this: how much and what you say to your child from their first few days literally carves new paths in their brain. We know this from research on speech development. When mothers responded to their babies’ cues with the most basic vocalisations, they accelerated their children’s language development. So go ahead and babble along with your toddler.

Kids need life on the highest volume

This article is based on the author’s experiences as a teacher in state schools in the US. I should imagine the situation is exacerbated there, but it can’t be that great elsewhere, either.

My own kids seem like they’re OK. Our youngest, whose had Covid like me this week, has gone back to remote learning, which she enjoys as she completes her work quickly and then does other things. I think it’s particularly hard on teenagers, like our eldest, who are preparing for important exams.

The data about learning loss and the mental health crisis is devastating. Overlooked has been the deep shame young people feel: Our students were taught to think of their schools as hubs for infection and themselves as vectors of disease. This has fundamentally altered their understanding of themselves.Source: I’m a Public School Teacher. The Kids Aren’t Alright. | Common SenseWhen we finally got back into the classroom in September 2020, I was optimistic, even as we would go remote for weeks, sometimes months, whenever case numbers would rise. But things never returned to normal.

When we were physically in school, it felt like there was no longer life in the building. Maybe it was the masks that made it so no one wanted to engage in lessons, or even talk about how they spent their weekend. But it felt cold and soulless. My students weren’t allowed to gather in the halls or chat between classes. They still aren’t. Sporting events, clubs and graduation were all cancelled. These may sound like small things, but these losses were a huge deal to the students. These are rites of passages that can’t be made up.

[…]

They are anxious and depressed. Previously outgoing students are now terrified at the prospect of being singled out to stand in front of the class and speak. And many of my students seem to have found comfort behind their masks. They feel exposed when their peers can see their whole face.

[…]

At the beginning of the pandemic, adults shamed kids for wanting to play at the park or hang out with their friends. We kept hearing, “They’ll be fine. They’re resilient.” It’s true that humans, by nature, are very resilient. But they also break. And my students are breaking. Some have already broken.

When we look at the Covid-19 pandemic through the lens of history, I believe it will be clear that we betrayed our children. The risks of this pandemic were never to them, but they were forced to carry the burden of it. It’s enough. It’s time for a return to normal life and put an end to the bureaucratic policies that aren’t making society safer, but are sacrificing our children’s mental, emotional, and physical health.

Our children need life on the highest volume. And they need it now.

Friday finds

Check out these links that I came across this week and thought you'd find interesting:

Image from These gorgeous tiny houses can operate entirely off the grid (Fast Company)

Cutting the Gordian knot of 'screen time'

Let's start this with an admission: my wife and I limit our children's time on their tablets, and they're only allowed on our games console at weekends. Nevertheless, I still maintain that wielding 'screen time' as a blunt instrument does more harm than good.

There's a lot of hand-wringing on this subject, especially around social skills and interaction. Take a recent article in The Guardian, for example, where Peter Fonagy, who is a professor of Contemporary Psychoanalysis and Developmental Science at UCL, comments:

“My impression is that young people have less face-to-face contact with older people than they once used to. The socialising agent for a young person is another young person, and that’s not what the brain is designed for.

“It is designed for a young person to be socialised and supported in their development by an older person. Families have fewer meals together as people spend more time with friends on the internet. The digital is not so much the problem – it’s what the digital pushes out.”

I don't disagree that we all need a balance here, but where's the evidence? On balance, I spend more time with my children than my father spent with my sister and I, yet my wife, two children and me probably have fewer mealtimes sat down at a table together than I did with my parents and sister. Different isn't always worse, and in our case it's often due to their sporting commitments.

So I'd agree with Jordan Shapiro who writes that the World Health Organisation's guidelines on screen time for kids isn't particularly useful. He quotes several sources that dismiss the WHO's recommendations:

Andrew Przybylski, the Director of Research at the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, said: “The authors are overly optimistic when they conclude screen time and physical activity can be swapped on a 1:1 basis.” He added that, “the advice overly focuses on quantity of screen time and fails to consider the content and context of use. Both the American Academy of Pediatricians and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health now emphasize that not all screen time is created equal.”

That being said, parents still need some guidance. As I've said before, my generation of parents are the first ones having to deal with all of this, so where do we turn for advice?

An article by Roja Heydarpour suggests three strategies, including one from Mimi Ito who I hold in the utmost respect for her work around Connected Learning:

“Just because [kids] may meet an unsavory person in the park, we don’t ban them from outdoor spaces,” said Mimi Ito, director of the Connected Learning Lab at University of California-Irvine, at the 10th annual Women in the World Summit on Thursday. After years of research, the mother of two college-age children said she thinks parents need to understand how important digital spaces are to children and adjust accordingly.

Taking away access to these spaces, she said, is taking away what kids perceive as a human right. Gaming is like the proverbial water cooler for many boys, she said. And for many girls, social media can bring access to friends and stave off social isolation. “We all have to learn how to regulate our media consumption,” Ito said. “The longer you delay kids being able to use those muscles, the longer you delay kids learning how to regulate.”

I feel a bit bad reading that, as we've recently banned my son from the game Fortnite, which we felt was taking over his life a little too much. It's not forever, though, and he does have to find that balance between it having a place in his life and literally talking about it all of the freaking time.

One authoritative voice in the area is my friend and sometimes collaborator Ian O'Byrne, who, together with Kristen Hawley Turner, has created screentime.me which features a blog, podcast, and up-to-date research on the subject. Well worth checking out!

Also check out:

Let's not force children to define their future selves through the lens of 'work'

I discovered the work of Adam Grant through Jocelyn K. Glei's excellent Hurry Slowly podcast. He has his own, equally excellent podcast, called WorkLife which he creates with the assistance of TED.

Writing in The New York Times as a workplace psychologist, Grant notes just how problematic the question "what do you want to be when you grow up?" actually is:

When I was a kid, I dreaded the question. I never had a good answer. Adults always seemed terribly disappointed that I wasn’t dreaming of becoming something grand or heroic, like a filmmaker or an astronaut.

Let's think: from what I can remember, I wanted to be a journalist, and then an RAF pilot. Am I unhappy that I'm neither of these things? No.

Perhaps it's because a job is more tangible than an attitude or approach to life, but not once can I remember being asked what kind of person I wanted to be. It was always "what do you want to be when you grow up?", and the insinuation was that the answer was job-related.

My first beef with the question is that it forces kids to define themselves in terms of work. When you’re asked what you want to be when you grow up, it’s not socially acceptable to say, “A father,” or, “A mother,” let alone, “A person of integrity.”

[...]

The second problem is the implication that there is one calling out there for everyone. Although having a calling can be a source of joy, research shows that searching for one leaves students feeling lost and confused.

Another fantastic podcast episode I listened to recently was Tim Ferriss' interview of Caterina Fake. She's had an immensely successful career, yet her key messages during that conversation were around embracing your 'shadow' (i.e. melancholy, etc.) and ensuring that you have a rich inner life.

While the question beloved of grandparents around the world seems innocuous enough, these things have material effects on people's lives. Children are eager to please, and internalise other people's expectations.

I’m all for encouraging youngsters to aim high and dream big. But take it from someone who studies work for a living: those aspirations should be bigger than work. Asking kids what they want to be leads them to claim a career identity they might never want to earn. Instead, invite them to think about what kind of person they want to be — and about all the different things they might want to do.

The jobs I've had over the last decade didn't really exist when I was a child, so it would have been impossible to point to them. Let's encourage children to think of the ways they can think and act to change the world for the better - not how they're going to pay the bills to enable themselves to do so.

Source: The New York Times

Also check out:

What UK children are watching (and why)

There were only 40 children as part of this Ofcom research, and (as far as I can tell) none were in the North East of England where I live. Nevertheless, as parent to a 12 year-old boy and eight year-old girl, I found the report interesting.

Key findings:I've recently volunteered as an Assistant Scout Leader, and last night went with Scouts and Cubs to the ice-rink in Newcastle on the train. As I'd expect, most of the 12 year-old boys had their smartphones out and most of the girls were talking to one another. The boys were playing some games, but were mostly watching YouTube videos of other people playing games.

All kids with access to screen watch YouTube. Why?

Until I saw my son really level up his gameplay by watching YouTubers play the same games as him, I didn't really get it. There's lots of moral panic about YouTube's algorithms, but there's also a lot to celebrate with the fact that children have a bit more autonomy and control these days.

The appeal of YouTube for many of the children in the sample seemed to be that they were able to feed and advance their interests and hobbies through it. Due to the variety of content available on the platform, children were able to find videos that corresponded with interests they had spoken about enjoying offline; these included crafts, sports, drawing, music, make-up and science. Notably, in some cases, children were watching people on YouTube pursuing hobbies that they did not do themselves or had recently given up offline.Really interesting stuff, and well worth digging into!

Source: Ofcom (via Benedict Evans)

Finding friends and family without smartphones, maps, or GPS

When I was four years old we moved to the North East of England. Soon after, my parents took my grandmother, younger sister (still in a pushchair) and me to the Quayside market in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

There’s still some disagreement as to how exactly it happened, but after buying a toy monkey that wrapped around my neck using velcro, I got lost. It’s a long time ago, but I can vaguely remember my decision that, if I couldn’t find my parents or grandmother, I’d probably better head back to the car. So I did.

45 minutes later, and after the police had been called, my parents found me and my monkey sitting on the bonnet of our family car. I can still remember the registration number of that orange Ford Escort: MAT 474 V.

Now, 33 years later, we’re still not great at ensuring children don’t get lost. Yes, we have more of a culture of ensuring children don’t go out of our sight, and give kids smartphones at increasingly-young ages, but we can do much better.

That’s why I thought this Lynq tracker, currently being crowdfunded via Indiegogo was such a great idea. You can get the gist by watching the promo video:

Our family is off for two weeks around Europe this summer. While we’ve been a couple of times before, both involved taking our car and camping. This time, we’re interrailing and Airbnbing our way around, which increases the risk that one of our children gets lost.

Lync looks really simple and effective to use, but isn’t going to be shipping until November, — otherwise I would have backed this in an instant.

Source: The Verge

The benefits of reading aloud to children

This article in the New York Times by Perri Klass, M.D. focuses on studies that show a link between parents reading to their children and a reduction in problematic behaviour.

I really like the way that they focus on the positives and point out how much the child loves the interaction with their parent through the text.This study involved 675 families with children from birth to 5; it was a randomized trial in which 225 families received the intervention, called the Video Interaction Project, and the other families served as controls. The V.I.P. model was originally developed in 1998, and has been studied extensively by this research group.

Participating families received books and toys when they visited the pediatric clinic. They met briefly with a parenting coach working with the program to talk about their child’s development, what the parents had noticed, and what they might expect developmentally, and then they were videotaped playing and reading with their child for about five minutes (or a little longer in the part of the study which continued into the preschool years). Immediately after, they watched the videotape with the study interventionist, who helped point out the child’s responses.

I don't know enough about the causes of ADHD to be able to comment, but as a teacher and parent, I do know there's a link between the attention you give and the attention you receive.The Video Interaction Project started as an infant-toddler program, working with low-income urban families in New York during clinic visits from birth to 3 years of age. Previously published data from a randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development showed that the 3-year-olds who had received the intervention had improved behavior — that is, they were significantly less likely to be aggressive or hyperactive than the 3-year-olds in the control group.

It is a bit sad when we have to encourage parents to play with children between the ages of birth and three, but I guess in the age of smartphone addiction, we kind of have to.“The reduction in hyperactivity is a reduction in meeting clinical levels of hyperactivity,” Dr. Mendelsohn said. “We may be helping some children so they don’t need to have certain kinds of evaluations.” Children who grow up in poverty are at much higher risk of behavior problems in school, so reducing the risk of those attention and behavior problems is one important strategy for reducing educational disparities — as is improving children’s language skills, another source of school problems for poor children.

Source: The New York Times

Image CC BY Jason Lander

Decision fatigue and parenting

Our 11 year-old still asks plenty of questions, but also looks things up for himself online. Our seven year-old fires off barrages of questions when she wakes up, to and from school, during dinner, before bed — basically anytime she can get a word in edgeways.

I have sympathy, therefore, for Emma Marris, who decided to show those who aren’t parents of young children (or perhaps those who have forgotten) what it’s like.

I decided to write down every question that required a decision that my my two kids asked me during a single day. This doesn’t include simple requests for information like “how do you spell ‘secret club’?” or “what is the oldest animal in the world?” or the perennial favorite, “why do people have to die?” Recording ALL the questions two kids ask in a day would be completely intractable. So, limiting myself to just those queries that required a decision, here are the results.Some of my favourites from her long list:

I’m not saying we’re amazing parents, but one thing we try and do is to not just tell our children the answer to their questions, but tell them how we worked it out. That’s particularly important if we used some kind of device to help us find the answer. Recently, I’ve been using the Google Assistant which feels to an adult almost interface-free. However, there’s a definite knack to it that you forget once you’re used to using it.

Over and above that, a lot of questions that children ask are permission and equality-related. In other words, they’re asking if they’re allowed to do something, or if you’ll intervene because the other child is doing something they shouldn’t / gaining an advantage. Both my wife and I have been teachers, and the same is true in the classroom.

There’s a couple of things I’ve learned here:

Decision fatigue is real. Decision fatigue is the mental exhaustion and reduced willpower that comes from making many, many micro-calls every day. My modern American lifestyle, with its endless variety of choices, from a hundred kinds of yogurt at the grocery store to the more than 4,000 movies available on Netflix, breeds decision fatigue. But it is my kids that really fry my brain. At last I understand that my own mother’s penchant for saying “ask your father” wasn’t deference to her then husband but the most desperate sort of buck-passing–especially since my father dealt with decision fatigue by saying yes to pretty much everything, which is how my brothers and I ended up taking turns rolling down the steep hill we grew up on inside an aluminum trash can.Source: The Last Word on Nothing

On playing video games with your kids

I play ‘video games’ (a curiously old-fashioned term) with my kids all the time. Current favourites are FIFA 18 and Star Wars Battlefront II. We also enjoy Party Golf as a whole family (hilarious!)

My children play different games with each other than they play with me. They’re more likely to play Lego Worlds or Minecraft (the latter always on their tablets). And when I’m away we play word games such as Words With Friends 2 or Wordbase.

The author of this article, David Cole, points out that playing games with his son is a different experience than he was expecting it to be:

So when I imagined playing video games with my son — now 6 — I pictured myself as being the Player 2 that I’d never had in my own childhood. I wouldn’t mind which games he wanted to play, or how many turns he’d take. I would comfort him through frustrating losses and be a good sport when we competed head-to-head. What I hadn’t anticipated in these fantasies was how much a new breed of video game would end up deeply altering the way we relate. Games of challenge and reflex are still popular of course, but among children my son’s age they’ve been drastically overtaken by a class of games defined by open-ended, expressive play. The hallmark title of this sort is, undeniably, Minecraft.

My son is 11 years old and my daughter seven, so what Cole describes resonates:

My son and I do still play those competitive games, and I hope that he’s learning about practice and perseverance when we do. But those games are about stretching and challenging him to fit the mold of the game’s demands. When we play Minecraft together, the direction of his development, and thus our relationship, is reversed: He converts the world into expressions of his own fantasies and dreams. And by letting me enter and explore those dream worlds with him, I come to understand him in a way that the games from my childhood do not.

The paragraph that particularly resonated with me was this one, as it not only describes my relationship with my children when playing video games, but also parenting as being vastly different (for better and worse) than I thought it would be:

The working rhythms of our shared play allow for stretches of silent collaboration. It’s in these contemplative moments that I notice how distinct this feeling is from my own childhood, as well as the childhood I had predicted for my son. I thought I would be his Player 2, an ideal peer that would make his childhood awesome in ways that mine was not. In retrospect, that was always just a picture of me, not of him and not of us.

A lovely article that reminded me of the heartwarming Player 2 video short based on a true story from a YouTube comments section...

Source: The CutTeaching kids about computers and coding

Not only is Hacker News a great place to find the latest news about tech-related stuff, it’s also got some interesting ‘Ask HN’ threads sourcing recommendations from the community.

This particular one starts with a user posing the question:

Ask HN: How do you teach you kids about computers and coding?Like sites such as Reddit and Stack Overflow, responses are voted up based on their usefulness. The most-upvoted response was this one:Please share what tools & approaches you use - it may Scratch, Python, any kids specific like Linux distros, Raspberry Pi or recent products like Lego Boost… Or your experiences with them.. thanks.

My daughter is almost 5 and she picked up Scratch Jr in ten minutes. I am writing my suggestions mostly from the context of a younger child.But I think my favourite response is this one:I approached it this way, I bought a book on Scratch Jr so I could get up to speed on it. I walked her through a few of the basics, and then I just let her take over after that.

One other programming related activity we have done is the Learning Resources Code & Go Robot Mouse Activity. She has a lot of fun with this as you have a small mouse you program with simple directions to navigate a maze to find the cheese. It uses a set of cards to help then grasp the steps needed. I switch to not using the cards after a while. We now just step the mouse through the maze manually adding steps as we go.

One other activity to consider is the robot turtles board game. This teaches some basic logic concepts needed in programming.

For an older child, I did help my nephew to learn programming in Python when he was a freshman in high school. I took the approach of having him type in games from the free Python book. I have always though this was a good approach for older kids to get the familiar with the syntax.

Something else I would consider would be a robot that can be programmer with Scratch. While I have not done this yet, I think for kid seeing the physical results of programming via a robot is a powerful way to capture interest.

What age range are we talking about? For most kids aged 6-12 writing code is too abstract to start with. For my kids, I started making really simple projects with a Makey Makey. After that, I taught them the basics with Scratch, since there are tons of fun tutorials for kids. Right now, I'm building a Raspberry Pi-powered robot with my 10yo (basically it's a poor man's Lego Mindstorm).My son is sailing through his Computer Science classes at school because of some webmaking and ‘coding’ stuff we did when he was younger. He’s seldom interested, however, if I want to break out the Raspberry Pi and have a play.The key is fun. The focus is much more on ‘building something together’ than ‘I’ll learn you how to code’. I’m pretty sure that if I were to press them into learning how to code it will only put them off. Sometimes we go for weeks without building on the robot, and all of the sudden she will ask me to work on it with her again.

At the end of the day, it’s meeting them where they’re at. If they show an interest, run with it!

Source: Hacker News

Using VR with kids

I’ve seen conflicting advice regarding using Virtual Reality (VR) with kids, so it’s good to see this from the LSE:

I have given my two children (six and nine at the time) experience of VR — albeit in limited bursts. The concern I have is about eyesight, mainly.Children are becoming aware of virtual reality (VR) in increasing numbers: in autumn 2016, 40% of those aged 2-15 surveyed in the US had never heard of VR, and this number was halved less than one year later. While the technology is appealing and exciting to children, its potential health and safety issues remain questionable, as there is, to date, limited research into its long-term effects.

There's some good advice in this post for VR games/experience designers, and for parents. I'll quote the latter:As a young technology there are still many unknowns about the long-term risks and effects of VR gaming, although Dubit found no negative effects from short-term play for children’s visual acuity, and little difference between pre- and post-VR play in stereoacuity (which relies on good eyesight for both eyes and good coordination between the two) and balance tests. Only 2 of the 15 children who used the fully immersive head-mounted display showed some stereoacuity after-effects, and none of those using the low-cost Google Cardboard headset showed any. Similarly, a few seemed to be at risk of negative after-effects to their balance after using VR, but most showed no problems.

There's a surprising lack of regulation and guidance in this space, so it's good to see the LSE taking the initiative!While much of a child’s experience with VR may still be in museums, schools or other educational spaces under the guidance of trained adults, as the technology becomes more available in domestic settings, to ensure health and safety at home, parents and carers need to:

Source: Parenting for a Digital Future

The upside of kids watching Netflix instead of TV

In our house, on the (very) rare occasions we’re watching live television that includes advert breaks, I mute the sound and do a humourous voice-over…

With more homes than ever becoming ‘Netflix Only’ homes, we wanted to see how many hours of commercials kids in these homes are being spared. We were able to determine that kids in ‘Netflix Only’ homes are saved from just over 230 hours of commercials a year when compared to traditional television viewership homes.Source: Exstreamist