- Is pleasure all that is good about experience? (Journal of Philosophical Studies) — "In this article I present the claim that hedonism is not the most plausible experientialist account of wellbeing. The value of experience should not be understood as being limited to pleasure, and as such, the most plausible experientialist account of wellbeing is pluralistic, not hedonistic."

- Strong Opinions Loosely Held Might be the Worst Idea in Tech (The Glowforge Blog) — "What really happens? The loudest, most bombastic engineer states their case with certainty, and that shuts down discussion. Other people either assume the loudmouth knows best, or don’t want to stick out their neck and risk criticism and shame. This is especially true if the loudmouth is senior, or there is any other power differential."

- Why Play a Music CD? ‘No Ads, No Privacy Terrors, No Algorithms’ (The New York Times) — "What formerly hyped, supposedly essential technology has since been exposed for gross privacy violations, or for how easily it has become a tool for predatory disinformation?"

- Wet Plate Photography Makes Tattoos Disappear (PetaPixel) — the photographic technology in the 1800s used to photographic the indigenous Māori people of New Zealand didn't show their facial tattoos.

- Archive shows medieval nun faked her own death to escape convent (The Guardian) — entertaining, but also pretty tragic if you think about the number of young women 'sent away' to convents in the past.

- Why Do People With Depression Like Listening To Sad Music? (The British Psychological Society) — no definitive answers, but seems to back up the commonsense assumption that high-energy music when you're feeling down is just annoying.

- We studied what 10,000 people love online. The results would make Freud blush (Fast Company) — dark nudges, disaster porn, and harder/faster/weirder algorithms.

- The Case for Doing Nothing (The New York Times) — reminiscent of Jocelyn K. Glei's question: "who are you without the doing?"

- The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education (Highline) — "As our most trusted universities continue to privatize large swaths of their academic programs, their fundamental nature will be changed in ways that are hard to reverse. The race for profits will grow more heated, and the social goal of higher education will seem even more like an abstraction."

- Social Peacocking and the Shadow (Caterina Fake) — "Social peacocking is life on the internet without the shadow. It is an incomplete representation of a life, a half of a person, a fraction of the wholeness of a human being."

- Why and How Capitalism needs to be reformed (Economic Principles) — "The problem is that capitalists typically don’t know how to divide the pie well and socialists typically don’t know how to grow it well."

What if I never change?

Oliver Burkeman on Jocelyn K. Glei’s Hurrry Slowly is an absolute treat. In particular, he quotes Jim Benson on how we can easily become “a limitless reservoir for other people’s expectations”. I also liked the discussion around the “internalised capitalism” of “clock time”.

The title comes from an important point that Burkeman makes about so many of our hopes and dreams being based on somehow in the future being a radically different person to who we are now.

It reminded me of a section in Alain de Botton’s The Art of Travel in which he summarises Seneca by saying that the problem about going somewhere to escape things is that you always take yourself (and your mental/emotional baggage) with you…

Oliver Burkeman on why we try to control time, how perfectionism holds us back, and the problems with a “when-i-finally” mindset.Source: Oliver Burkeman: What if I never change? | Hurry Slowly

Taking breaks to be more human

I have to say that I’m a bit sick of the narrative that we need time off / to recharge so we can be better workers. Instead, I’d prefer framing it as Jocelyn K. Glei does as asking yourself the question “who are you without the doing?”

The point isn’t just that it’s nice to goof off every so often — it’s that it’s necessary. And that’s true even if your ultimate goal is doing better work: Downtime allows the brain to make new connections and better decisions. Multiple studies have found that sustained mental attention without breaks is depleting, leading to inferior performance and decision-making.Source: How to Take a Break | The New York TimesIn short, the prefrontal cortex — where goal-oriented and executive-function thinking goes on — can get worn down, potentially resulting in “decision fatigue.” A variety of research finds that even simple remedies like a walk in nature or a nap can replenish the brain and ultimately improve mental performance.

If you change nothing, nothing will change

What would you do if you knew you had 24 hours left to live? I suppose it would depend on context. Is this catastrophe going to affect everyone, or only you? I'm not sure I'd know what to do in the former case, but once I'd said my goodbyes to my family, I'm pretty sure I know what I'd do in the latter.

Yep, I would go somewhere by myself and write.

To me, the reason both reading and writing can feel so freeing is that they allow you to mentally escape your physical constraints. It almost doesn't matter what's happening to your body or anything around you while you lose yourself in someone else's words, or you create your own.

I came across an interesting blog recently. It had a single post, entitled Consume less, create more. In it, the author, 'Tom', explains that the 1,600 words he's shared were written over the course of a month after he realised that he was spending his life consuming instead of creating.

A lot of ink has been spilled about the perils of modern technology. How it distracts us, how it promotes unhealthy comparisons with others, how it makes us fat, how it limits social interaction, how it spies on us. And all of these things are probably true, to some extent.

But the real tragedy of modern technology is that it’s turned us into consumers. Our voracious consumption of media parallels our consumption of fossil fuels, corn syrup, and plastic straws. And although we’re starting to worry about our consumption of those physical goods, we seem less concerned about our consumption of information.

We treat information as necessarily good, and comfort ourselves with the feeling that whatever article or newsletter we waste our time with is actually good for us. We equate reading with self improvement, even though we forget most of what we’ve read, and what we remember isn’t useful.

TJCX

I feel that at this juncture in history, we've perfected surveillance-via-smartphone as the perfect tool to maximise FOMO. For those growing up in the goldfish bowl of the modern world, this may feel as normal as the 'water' in which they are 'swimming'. But for the rest of us, it can still feel... odd.

This is going to sound pretty amazing, but I don't think there's been many days in my adult life when I've been able to go somewhere without anyone else knowing. As a kid? Absolutely. I can vividly remember, for example, cycling to a corn field and finding a place to lie down and look at the sky, knowing that no-one could see me. It was time spent with myself, unmediated and unfiltered.

This didn't used to be unusual. People had private inner lives that were manifested in private actions. In a recent column in The Guardian, Grace Dent expanded on this.

Yes life after iPhones is marvellous, but in the 90s I ran wild across London, up to all kinds of no good, staying out for days, keeping my own counsel entirely. My parents up north would not speak to me for weeks. Sometimes, life back in the days when we had one shit Nokia and a landline between five friends seems blissful. One was permitted lost weekends and periods of secret skulduggery or just to lie about reading a paperback without the sense six people were owed a text message. Yes, things took longer, and one needed to make plans and keep them, but being off the grid was normal. Today, not replying... is a truly radical act.

Grace Dent

"Not replying... is a truly radical act". Wow. Let that sink in for a moment.

Given all this, it's no wonder in our always-on culture that we have so much 'life admin' to concern ourselves with. Previous generations may have had 'pay the bills' on their to-do list, but it wasn't nudged down the to-do list by 'inform a person I kind of know on Twitter that they have incorrect view on Brexit'.

All of these things build upon incrementally until they eventually become unsustainable. It's death by a thousand cuts. As I've quoted many times before before, Jocelyn K. Glei's question is always worth asking: who are you without the doing?

Realistically, most of our days are likely to involve some use of digital communication tools. We can't always be throwing off our shackles to live the life of a flâneur. To facilitate space to create, therefore, it's important to draw some red lines. This is what Michael Bernstein talks about in Sorry, we can't join your Slack.

Saying yes to joining client Slack channels would mean that down the line we’d feel more exhausted but less accomplished. We’d have more superficial “friends,” but wouldn’t know how to deal with products much better than we did now. We’d be on the hook all the time, and have less of an opportunity to consider our responses.

Michael Bernstein

In other words, being more available and more 'social' takes time away from more important pursuits. After all, time is the ultimate zero-sum game.

Ultimately, I guess it's about learning to see the world differently. There very well be a 'new normal' that we've begun to internalise but, for now at least, we have a choice to use to our advantage that 'flexibility' we hear so much about.

This is why self-reflection is so important, as Wanda Thibodeaux explains in an article for Inc.

In sum, elimination of stress and the acceptance of peace comes not necessarily from changing the world, but rather from clearing away all the learned clutter that prevents us from changing our view of the world. Even the biggest systemic "realities" (e.g., work "HAS" to happen from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.) are up for reinterpretation and rewriting, and arguably, inner calm and innovation both stem from the same challenge of perceptions.

Wanda Thibodeaux

To do this, you have to have to already have decided the purpose for which you're using your tools, including the ones provided by your smartphone.

Need more specific advice on that? I suggest you go and read this really handy post by Ryan Holiday: A Radical Guide to Spending Less Time on Your Phone. The advice to be focused on which apps you need on your phone is excellent; I deleted over 100!

You may also find this post useful that I wrote over on my blog a few months ago about how changing the 'launcher' on your phone can change your life.

If you make some changes after reading this, I'd be interested in hearing how you get on. Let me know in the comments section below!

Quotation-as-title from Rajkummar Rao.

Aren’t you ashamed to reserve for yourself only the remnants of your life and to dedicate to wisdom only that time can’t be directed to business?

Once you remove the specific details from the lives of the ancients, their lives were remarkably like ours. Take today's title, for example, which is a quotation from Seneca. He knew what it was like to be so busy doing 'productive' things to the exclusion of almost everything else.

My good friend Laura Hilliger wears her heart on her sleeve, and is the most no-nonsense person I know. By observing the way she lives and works, I'm learning to set limits and say exactly what I think:

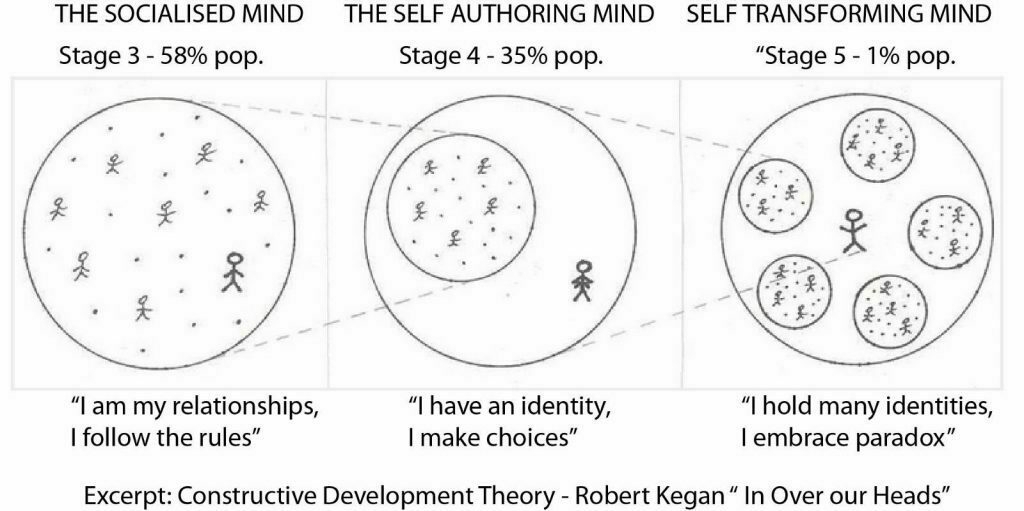

The thing is that western society, implicitly at least, assumes that people are 'fixed' in terms of their personality and likes. But that's just the way that we choose to see ourselves:

I feel that the biggest thing that constrains us is our view of how we think other people see us. That perceived expectation becomes internalised, creating a 'psychic prison' which becomes an extremely limited playground. For better or for worse, we perform the role of how we think other people have come to see us.

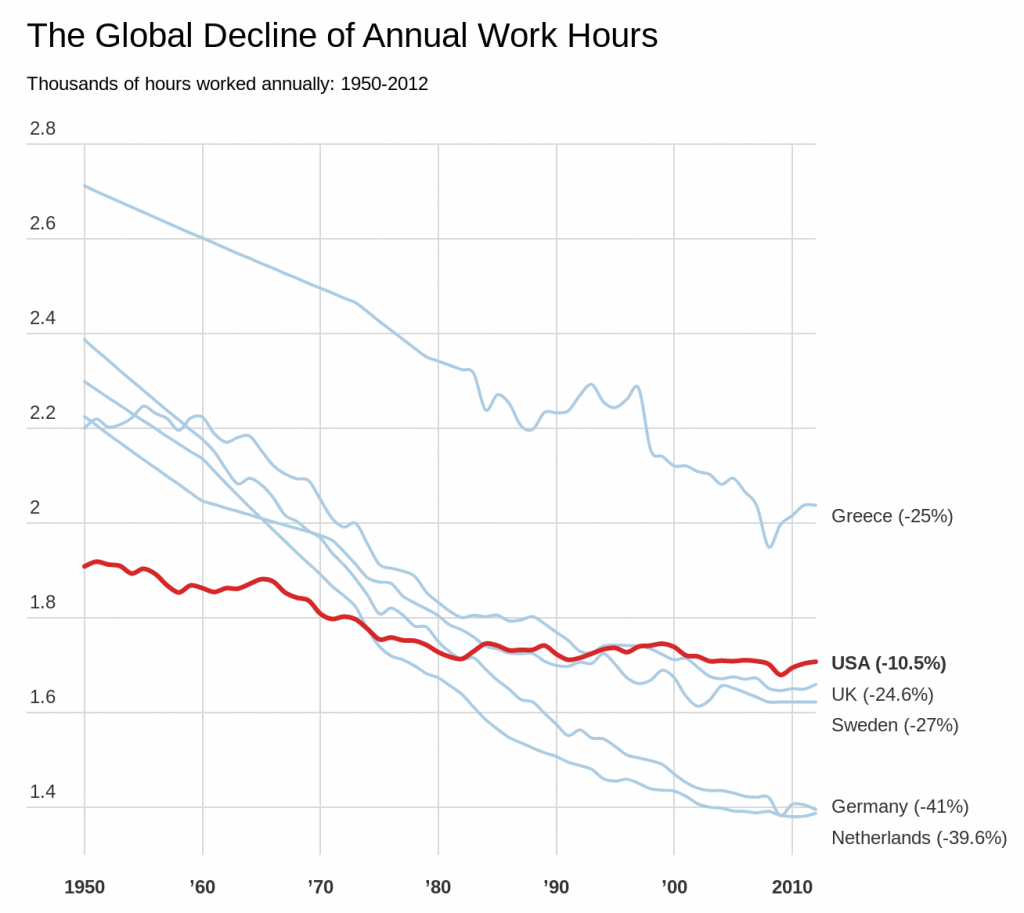

One way many people find to avoid responsibility for their life choices is to play the 'busy' card. They're too busy to make good decisions, to look after their mental and physical health, to ensure that they're doing your best work.

The trouble is, that's simply not true. We've got more free time than our parents and grandparents:

As the above chart demonstrates, it's not true that we actually work more hours. Instead, I think, it's that we're so concerned about how other people see us that we spend time doing things that feel like work but are mostly to do with presentation of self. Hence the amount of time spent on social networks like Instagram trying to create the highlights reel of our lives to show others.

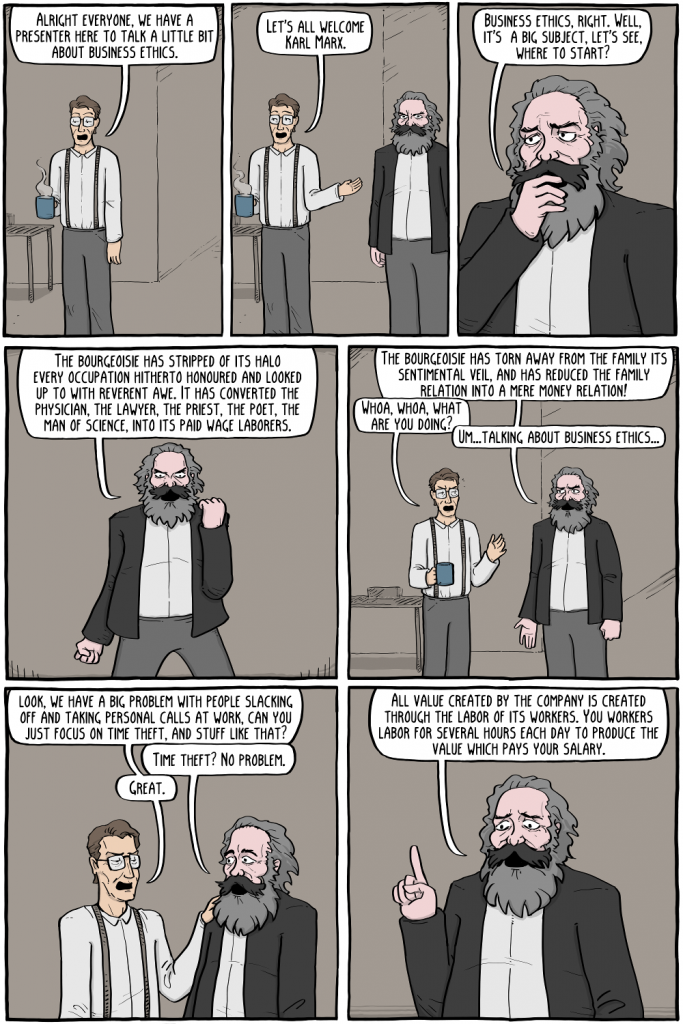

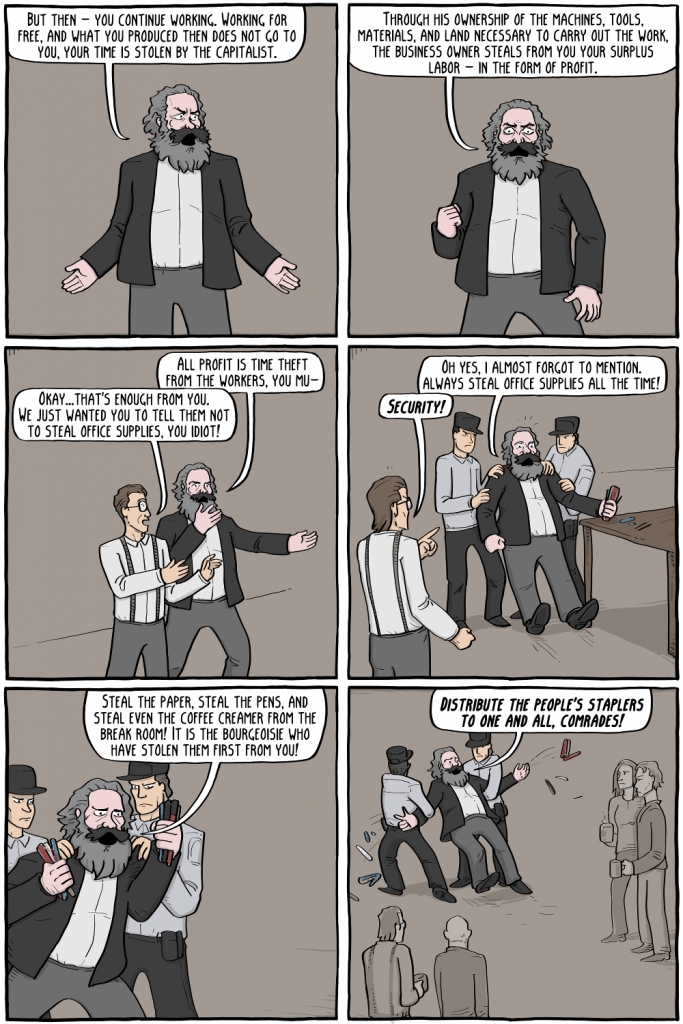

One way of viewing this is that we've collectively internalised capitalism. The logic of the market has become as invisible to us as an ideology as water is to fish. In fact, some people say it's easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism!

Of course, it's become something of a cliché in our pseudo-enlightened times to talk of capitalism as the meta-problem behind everything. But that doesn't make it any less true.

Our identity is mediated by the market, by what we produce instead of who we are. I keep coming back to a fantastic episode of Jocelyn K. Glei's Hurry Slowly podcast entitled Who Are You Without The Doing? in which she explains that we should learn to 'sit with ourselves', learning that change comes from within:

You have to completely conquer the feeling that there is something fundamentally wrong with your human nature, and that therefore you need discipline to correct your behavior. As long as you feel the discipline comes from the outside, there is still a feeling that something is lacking in you.

Jocelyn K. Glei

Derek Sivers uses the metaphor of 'doors' to explain where he finds value and wants to spend time doing. Some doors he opens and it helps him grow as a person and fosters positive relationships.

But one door is really no fun to open. I’m horrified at all the shouting, the second I open it. It’s an infinite dark room filled with psychologically tortured people, trying to get attention. Strangers screaming at strangers, starting fights. Businesses set up shop there, showing who’s said and done bad things today, because they make money when people get mad.

Derek Sivers

We keep wringing our hands about people's behaviour online, but it's that way for a reason. Hate is profitable for social networks:

Massive platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube “optimize for engagement,” and make automatic, algorithmic suggestions for every bit of content or action. From “you might also like” to “recommended just for you” to prioritizing things — anything — that will get you to click, comment, or share.

[...]

They know what will catch your attention. They know what will get you “engaged.” They know what will be more likely to lead you deeper into a rabbit hole, and what will make it harder to climb back out. Is it a literal, iron-clad trap? No. But the slippery, spiral path that leads people to the darkest corners of the internet is not an accident.

[...]

Hate is profitable. Conflict is profitable. Schadenfreude and shame are profitable. While we smugly point fingers, tsk-tsk, and think we’re being clever as we strategically dole out likes and shares, we forget that we are all just gruel-fed hamsters running on wheels deep inside giant, hyper-engineered, artificially intelligent, fully gamified, corporate-controlled virtual worlds that we absurdly think belong to us.

Ryan Ozawa

This all comes back to the time equation. Because we feel like we don't have enough time to curate things ourselves, we outsource that to others. That ends up with handing our information environments over to others to manipulate and control. It's curate or be curated.

Nobody cares about how much money you earn. Nobody cares how productive you are. Not really.

Also, without sounding harsh, nobody else cares how productive you are. Of course, productivity is important for important things, and “getting stuff done” or whatever, but it doesn’t define you in any way. What does is things like your sense of humour, where your passions lie, how you comfort a friend who’s upset, and that weird noise you make when the delivery guy calls you to say he’s outside with your food.

Leila Mitwally

The trouble is that we don't want to have this conversation, because it questions our identity, and everything we've been working for over our careers and throughout our lives:

But we don’t want to hear that because accepting this truth means asking a lot of complicated questions about our society, in which work is glorified as the pinnacle of self-expression, and personal earnings are viewed as a measure of merit and esteem.

Instead, we would instead read about buy into the idea that success in our work life is a merely a matter of being more productive. If you just follow the ‘right’ set of algorithms or rules, you too can achieve ‘success’ in your work life, along with fame and recognition and a fat bank account.

Richard Whittall

So, to finish, let me revisit a link I shared recently from Jason Hickel. We can choose to live differently, to recognise the abundance of time and resources we have in the world. To slow down, to take stock, and reject economic growth as in any way a useful indicator of human flourishing:

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can call a halt to the madness – throw a wrench in the juggernaut. By de-enclosing social goods and restoring the commons, we can ensure that people are able to access the things that they need to live a good life without having to generate piles of income in order to do so, and without feeding the never-ending growth machine. “Private riches” may shrink, as Lauderdale pointed out, but public wealth will increase.

Jason Hickel

It doesn't have to be difficult. We can just, as Dan Lyons mentions in his book Lab Rats, decide to work on things that 'close the gap' or 'increase the gap'. What that means to you, in your context, is a different matter.

Man must choose whether to be rich in things or in the freedom to use them

So said Ivan Illich. Another person I can imagine saying that is Diogenes the Cynic, perhaps my favourite philosopher of all time. He famously lived in a large barrel, sometimes pretended he was a dog, and allegedly told Alexander the Great to stand out of his sunlight.

What a guy. The thing that Diogenes understood is that freedom is much more important than power. That's the subject of a New York Times Op-Ed by essayist and cartoonist Tim Kreiger, who explains:

I would define power as the ability to make other people do what you want; freedom is the ability to do what you want. Like gravity and acceleration, these are two forces that appear to be different but are in fact one. Freedom is the defensive, or pre-emptive, form of power: the power that’s necessary to resist all the power the world attempts to exert over us from day one. So immense and pervasive is this force that it takes a considerable counterforce just to restore and maintain mere autonomy. Who was ultimately more powerful: the conqueror Alexander, who ruled the known world, or the philosopher Diogenes, whom Alexander could neither offer nor threaten with anything? (Alexander reportedly said that if he weren’t Alexander, he would want to be Diogenes. Diogenes said that if he weren’t Diogenes, he’d want to be Diogenes too.)

Tim Kreider

Of course, Tim is a privileged white dude, just like me. His opinion piece does, however, give us an interesting way into the cultural phenomenon of young white men opting out of regular employment.

As Andrew Fiouzi writes for Mel Magazine, the gap between what you're told (and what you see your older relatives achieving) and what you're offered can sometimes be stark. Michael Madowitz, an economist at the Center for American Progress, is cited by Fiouzi in the article.

While there’s a lot of speculation as to why this is the case, Madowitz says it has little to do with the common narrative that millennial men are too busy playing video games. Instead, he argues that millennials... who entered the labor market at a time when it was less likely than ever to adequately reward them for their work — “I couldn’t get any interviews and I tried doing some freelance stuff, but I could barely find anything, so I took an unpaid internship at a design agency,” says [one example] — were simply less likely to feel the upside of working.

Andrew Fiouzi

By default in our western culture, no matter how much a man earns, if he's in a hetrosexual relationship, then it's the woman who becomes the care-giver after they have children. I think that's changing a bit, and men are more likely to at least share the responsibilities.

So in the end, it may be the very inflexibility of an economy built on traditional gender roles that ultimately brings down the male-dominated labor apparatus, one stay-at-home dad at a time.

ANDREW FIOUZI

Part of the problem, I think, is the constant advice to 'follow your heart' and find work that's 'your passion'. While I think you absolutely should be guided by your values, how that plays out depends a lot on context.

Pavithra Mohan takes this up in an article for Fast Company. She writes:

Sometimes, compensation or job function may be more important to you than meaning, while at other times location and flexibility may take precedence.

[...]

Something that can get lost in the conversation around meaningful work is that even pursuing it takes privilege.

[...]

Making an impact can also mean very different things to different people. If you feel fulfilled by your family or social life, for example, being connected to your work may not—and need not—be of utmost importance. You might find more meaning in volunteer work or believe you can make more of an impact by practicing effective altruism and putting the money you earn towards charitable causes.

Pavithra Mohan

I've certainly been thinking about that this Bank Holiday weekend. What gets squeezed out in your personal life, when you're busy trying to find the perfect 'work' life? Or, to return to a question that Jocelyn K. Glei asks, who are you without the doing?

Also check out:

Fascinating Friday Facts

Here's some links I thought I'd share which struck me as interesting:

Header image: Keep out! The 100m² countries – in pictures (The Guardian)

Let's not force children to define their future selves through the lens of 'work'

I discovered the work of Adam Grant through Jocelyn K. Glei's excellent Hurry Slowly podcast. He has his own, equally excellent podcast, called WorkLife which he creates with the assistance of TED.

Writing in The New York Times as a workplace psychologist, Grant notes just how problematic the question "what do you want to be when you grow up?" actually is:

When I was a kid, I dreaded the question. I never had a good answer. Adults always seemed terribly disappointed that I wasn’t dreaming of becoming something grand or heroic, like a filmmaker or an astronaut.

Let's think: from what I can remember, I wanted to be a journalist, and then an RAF pilot. Am I unhappy that I'm neither of these things? No.

Perhaps it's because a job is more tangible than an attitude or approach to life, but not once can I remember being asked what kind of person I wanted to be. It was always "what do you want to be when you grow up?", and the insinuation was that the answer was job-related.

My first beef with the question is that it forces kids to define themselves in terms of work. When you’re asked what you want to be when you grow up, it’s not socially acceptable to say, “A father,” or, “A mother,” let alone, “A person of integrity.”

[...]

The second problem is the implication that there is one calling out there for everyone. Although having a calling can be a source of joy, research shows that searching for one leaves students feeling lost and confused.

Another fantastic podcast episode I listened to recently was Tim Ferriss' interview of Caterina Fake. She's had an immensely successful career, yet her key messages during that conversation were around embracing your 'shadow' (i.e. melancholy, etc.) and ensuring that you have a rich inner life.

While the question beloved of grandparents around the world seems innocuous enough, these things have material effects on people's lives. Children are eager to please, and internalise other people's expectations.

I’m all for encouraging youngsters to aim high and dream big. But take it from someone who studies work for a living: those aspirations should be bigger than work. Asking kids what they want to be leads them to claim a career identity they might never want to earn. Instead, invite them to think about what kind of person they want to be — and about all the different things they might want to do.

The jobs I've had over the last decade didn't really exist when I was a child, so it would have been impossible to point to them. Let's encourage children to think of the ways they can think and act to change the world for the better - not how they're going to pay the bills to enable themselves to do so.

Source: The New York Times

Also check out:

Deliberate rest, cognitive momentum, and differentiated work hours

Appropriately enough, it was during a lunchtime run that I listened to the latest episode of Jocelyn K. Glei’s excellent podcast. It featured Alex Pang, writer and futurist, on the benefits of rest for the creative process.

He talked about a number of things, but it confirmed my belief that you can only really do four hours of focused, creative work per day. Of course, you can add status-update meetings and emails to that, but the core of anyone’s work should be this sustained, disciplined period of attention.

Four really concentrated hours are sufficient to do one’s most critical work, they’re sufficient to do really good work, and for whatever reason they seem to be the physical limit that most of us have.In addition, he introduced terms such as 'deliberate rest' and 'cognitive momentum' which I'll definitely be using in future. A highly recommended listen.

Source: Hurry Slowly