- More workers want to slow down to get things right — "In reality, 61% of workers said they wanted to “slow down to get things right” while only 41%* wanted to “go fast to achieve more.” The divide was even starker among older workers."

- Workers strongly value uninterrupted focus at work, but most will make an exception to help others — "The results suggest we need to be more thoughtful about when we break our concentration, or ask others to do so. When people know they are helping others in a meaningful way, they tend to be okay with some distraction. But the busywork of meetings, alerts, and emails can quickly disrupt a person’s flow—one of the most important values we polled."

- Most workers have slightly more trust in people closest to the work, rather than people in upper management — "Among all respondents, 53% trusted people “closest to the work,” while only 45% trusted “upper management.” You might assume that younger workers would be the most likely to trust peers over management, but in fact, the opposite was true."

- Workers are torn between idealism and pragmatism — "It’s tempting to assume that addressing just one piece—like taking a stand on societal issues—will necessarily get in the way of the work itself. But our research suggests we can begin to solve the two in tandem, as more equality, inclusion, and diversity tends to come hand-in-hand with a healthier mindset about work."

- Health effects of job insecurity (IZA) — "Workers’ health is not just a matter for employees and employers, but also for public policy. Governments should count the health cost of restrictive policies that generate unemployment and insecurity, while promoting employability through skills training."

- Will your organization change itself to death? (opensource.com) — "Sometimes, an organization returns to the same state after sensing a stimulus. Think about a kid's balancing doll: You can push it and it'll wobble around, but it always returns to its upright state... Resilient organizations undergo change, but they do so in the service of maintaining equilibrium."

- Your Brain Can Only Take So Much Focus (HBR) — "The problem is that excessive focus exhausts the focus circuits in your brain. It can drain your energy and make you lose self-control. This energy drain can also make you more impulsive and less helpful. As a result, decisions are poorly thought-out, and you become less collaborative."

The inner world as the ultimate prison

I wanted to quote so much of this article that it would have ended up being a Borges-like 1:1 map of the territory. Instead, I’ll simply share the part of Swarnali Mukherjee’s writing which resonated most with me.

Do go and read the whole thing.

(I discovered this via Substack Notes, in which I have no financial interest, but simply finding to be a chill and serendipitious alternative to other social media)

The problem is simple: most of us have normalized and even glorified the hustle for success. The issue lies not in the hustle itself but in the often overlooked aspect of burning out. When success is defined in terms of societal parameters such as wealth, fame, and the emphasis on building an identity, life's entire focus becomes sustaining and amplifying this ego at the cost of our well-being, both psychologically and physically. We reinvent spaces in our intellectual worlds to serve this gigantic ego that we have conjured over the years but seldom find true happiness there. Our inner world becomes our ultimate prison, from whose window our persistent illusion of success resembles fireworks, promising that we can achieve them as long as we stay in the prison. This is a subtle deception of our social constructs; we humans have meticulously constructed these labyrinths of illusions to shield ourselves from the truth that even if we are in service to our desires, they are influenced by external factors. In that manner, doing something because the world expects it, that you won’t be doing otherwise is also a form of imprisonment.Source: The Art of Disappearing | Berkana

Everyone hustles his life along, and is troubled by a longing for the future and weariness of the present

Thanks to Seneca for today's quotation, taken from his still-all-too-relevant On the Shortness of Life. We're constantly being told that we need to 'hustle' to make it in today's society. However, as Dan Lyons points out in a book I'm currently reading called Lab Rats: how Silicon Valley made work miserable for the rest of us, we're actually being 'immiserated' for the benefit of Venture Capitalists.

As anyone who's read Daniel Kahneman's book Thinking, Fast and Slow will know, there are two dominant types of thinking:

The central thesis is a dichotomy between two modes of thought: "System 1" is fast, instinctive and emotional; "System 2" is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. The book delineates cognitive biases associated with each type of thinking, starting with Kahneman's own research on loss aversion. From framing choices to people's tendency to replace a difficult question with one which is easy to answer, the book highlights several decades of academic research to suggest that people place too much confidence in human judgement.

WIkipedia

Cal Newport, in a book of the same name, calls 'System 2' something else: Deep Work. Seneca, Kahneman, and Newport, are all basically saying the same thing but with different emphasis. We need to allow ourselves time for the slower and deliberative work that makes us uniquely human.

That kind of work doesn't happen when you're being constantly interrupted, nor when you're in an environment that isn't comfortable, nor when you're fearful that your job may not exist next week. A post for the Nuclino blog entitled Slack Is Not Where 'Deep Work' Happens uses a potentially-apocryphal tale to illustrate the point:

On one morning in 1797, the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was composing his famous poem Kubla Khan, which came to him in an opium-induced dream the night before. Upon waking, he set about writing until he was interrupted by an unknown person from Porlock. The interruption caused him to forget the rest of the lines, and Kubla Khan, only 54 lines long, was never completed.

Nuclino blog

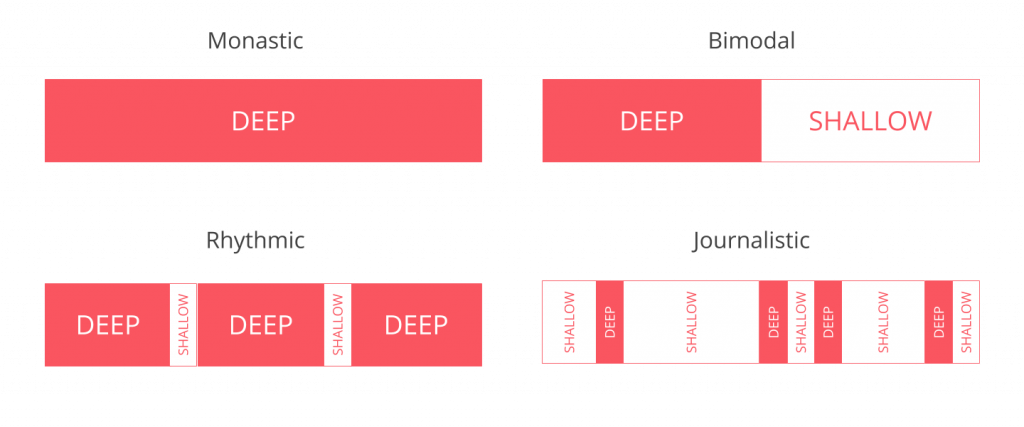

What we're actually doing by forcing everyone to use synchronous tools like Slack is a form of journalistic rhythm — but without everyone being synced-up:

If you haven't read Deep Work, never fear, because there's an epic article by Fadeke Adegbuyi for doist entitled The Complete Guide to Deep Work which is particularly useful:

This is an actionable guide based directly on Newport’s strategies in Deep Work. While we fully recommend reading the book in its entirety, this guide distills all of the research and recommendations into a single actionable resource that you can reference again and again as you build your deep work practice. You’ll learn how to integrate deep work into your life in order to execute at a higher level and discover the rewards that come with regularly losing yourself in meaningful work.

Fadeke Adegbuyi

Lots of articles and podcast episodes say they're 'actionable' or provide 'tactics' for success. I have to say this one delivers. I'd still read Newport's book, though.

Interestingly, despite all of the ridiculousness spouted by VC's, people are pretty clear about how they can do their best work. After a Dropbox survey of 500 US-based workers in the knowledge economy, Ben Taylor outlines four 'lessons' they've learned:

I think we need to reclaim workplace culture from the hustlers, shallow thinkers, and those focused on short-term profit. Let's reflect on how things actually work in practice. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb says about being 'antifragile', let's "look for habits and rules that have been around for a long time".

Also check out: