- Are we on the road to civilisation collapse? (BBC Future) — "Collapse is often quick and greatness provides no immunity. The Roman Empire covered 4.4 million sq km (1.9 million sq miles) in 390. Five years later, it had plummeted to 2 million sq km (770,000 sq miles). By 476, the empire’s reach was zero."

- Fish farming could be the center of a future food system (Fast Company) — "Aquaculture has been shown to have 10% of the greenhouse gas emissions of beef when it’s done well, and 50% of the feed usage per unit of production as beef"

- The global internet is disintegrating. What comes next? (BBC FutureNow) — "A separate internet for some, Facebook-mediated sovereignty for others: whether the information borders are drawn up by individual countries, coalitions, or global internet platforms, one thing is clear – the open internet that its early creators dreamed of is already gone."

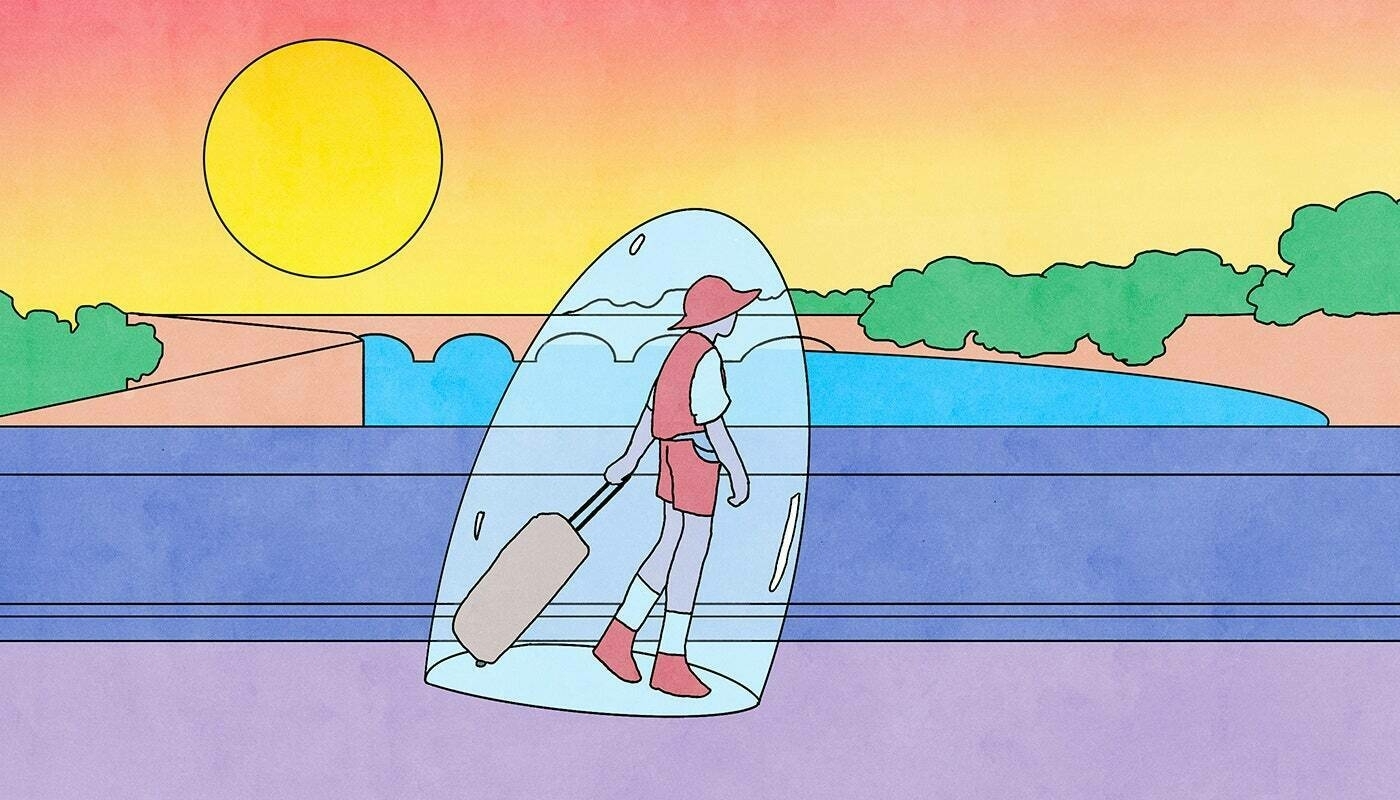

A philosophy of travel

There’s a book by philosopher Alain de Botton called The Art of Travel. In it, he cites Seneca as bemoaning the fact that when you travel you take yourself, with all of your anxieties, frustrations, and insecurities with you. In other words, you might escape your home, but you don’t escape yourself.

This article critically examines the concept of travel, questioning its oft-claimed benefits of ‘enlightenment’ and ‘personal growth’. It cites various thinkers who have critiqued travel (including one of my favourites, Fernando Pessoa) suggesting that it can actually distance us from genuine human connection and meaningful experiences.

It’s hard not to agree with the conclusion that the allure of travel may lie in its ability to temporarily distract us from the existential dread of mortality. Perhaps we need more Marcus Aurelius in our life, who extolled one the benefits of philosophy as being able to be find calm no matter where you are.

“A tourist is a temporarily leisured person who voluntarily visits a place away from home for the purpose of experiencing a change.” This definition is taken from the opening of “Hosts and Guests,” the classic academic volume on the anthropology of tourism. The last phrase is crucial: touristic travel exists for the sake of change. But what, exactly, gets changed? Here is a telling observation from the concluding chapter of the same book: “Tourists are less likely to borrow from their hosts than their hosts are from them, thus precipitating a chain of change in the host community.” We go to experience a change, but end up inflicting change on others.Source: The Case Against Travel | The New YorkerFor example, a decade ago, when I was in Abu Dhabi, I went on a guided tour of a falcon hospital. I took a photo with a falcon on my arm. I have no interest in falconry or falcons, and a generalized dislike of encounters with nonhuman animals. But the falcon hospital was one of the answers to the question, “What does one do in Abu Dhabi?” So I went. I suspect that everything about the falcon hospital, from its layout to its mission statement, is and will continue to be shaped by the visits of people like me—we unchanged changers, we tourists. (On the wall of the foyer, I recall seeing a series of “excellence in tourism” awards. Keep in mind that this is an animal hospital.)

Why might it be bad for a place to be shaped by the people who travel there, voluntarily, for the purpose of experiencing a change? The answer is that such people not only do not know what they are doing but are not even trying to learn. Consider me. It would be one thing to have such a deep passion for falconry that one is willing to fly to Abu Dhabi to pursue it, and it would be another thing to approach the visit in an aspirational spirit, with the hope of developing my life in a new direction. I was in neither position. I entered the hospital knowing that my post-Abu Dhabi life would contain exactly as much falconry as my pre-Abu Dhabi life—which is to say, zero falconry. If you are going to see something you neither value nor aspire to value, you are not doing much of anything besides locomoting.

[…]

The single most important fact about tourism is this: we already know what we will be like when we return. A vacation is not like immigrating to a foreign country, or matriculating at a university, or starting a new job, or falling in love. We embark on those pursuits with the trepidation of one who enters a tunnel not knowing who she will be when she walks out. The traveller departs confident that she will come back with the same basic interests, political beliefs, and living arrangements. Travel is a boomerang. It drops you right where you started.

[…]

Travel is fun, so it is not mysterious that we like it. What is mysterious is why we imbue it with a vast significance, an aura of virtue. If a vacation is merely the pursuit of unchanging change, an embrace of nothing, why insist on its meaning?

One can see only what one has already seen

Fernando Pessoa with today's quotation-as-title. He's best known for The Book of Disquiet which he called "a factless autobiography". It's... odd. Here's a sample:

Whether or not they exist, we're slaves to the gods.

Fernando pessoa

I've been reading a lot of Seneca recently, who famously said:

Life is divided into three periods, past, present and future. Of these, the present is short, the future is doubtful, the past is certain.

Seneca

The trouble is, we try and predict the future in order to control the future. Some people have a good track record in this, partly because they are involved in shaping things in the present. Other people have a vested interest in trying to get the world to bend to their ideology.

In an article for WIRED, Joi Ito, Director of the MIT Media Lab writes about 'extended intelligence' being the future rather than AI:

The notion of singularity – which includes the idea that AI will supercede humans with its exponential growth, making everything we humans have done and will do insignificant – is a religion created mostly by people who have designed and successfully deployed computation to solve problems previously considered impossibly complex for machines.

Joi Ito

It's a useful counter-balance to those banging the AI drum and talking about the coming jobs apocalypse.

After talking about 'S curves' and adaptive systems, Ito explains that:

Instead of thinking about machine intelligence in terms of humans vs machines, we should consider the system that integrates humans and machines – not artificial intelligence but extended intelligence. Instead of trying to control or design or even understand systems, it is more important to design systems that participate as responsible, aware and robust elements of even more complex systems.

Joi Ito

I haven't had a chance to read it yet, but I'm looking forward to seeing some of the ideas put forward in The Weight of Light: a collection of solar futures (which is free to download in multiple formats). We need to stop listening solely to rich white guys proclaiming the Silicon Valley narrative of 'disruption'. There are many other, much more collaborative and egalitarian, ways of thinking about and designing for the future.

This collection was inspired by a simple question: what would a world powered entirely by solar energy look like? In part, this question is about the materiality of solar energy—about where people will choose to put all the solar panels needed to power the global economy. It’s also about how people will rearrange their lives, values, relationships, markets, and politics around photovoltaic technologies. The political theorist and historian Timothy Mitchell argues that our current societies are carbon democracies, societies wrapped around the technologies, systems, and logics of oil.What will it be like, instead, to live in the photon societies of the future?

The Weight of Light: a collection of solar futures

We create the future, it doesn't just happen to us. My concern is that we don't recognise the signs that we're in the last days. Someone shared this quotation from the philosopher Kierkegaard recently, and I think it describes where we're at pretty well:

A fire broke out backstage in a theatre. The clown came out to warn the public; they thought it was a joke and applauded. He repeated it; the acclaim was even greater. I think that's just how the world will come to an end: to general applause from wits who believe it's a joke.

Søren Kierkegaard

Let's home we collectively wake up before it's too late.

Also check out: