- Some of your talents and skills can cause burnout. Here’s how to identify them (Fast Company) — "You didn’t mess up somewhere along the way or miss an important lesson that the rest of us received. We’re all dealing with gifts that drain our energy, but up until now, it hasn’t been a topic of conversation. We aren’t discussing how we end up overusing our gifts and feeling depleted over time."

- Learning from surveillance capitalism (Code Acts in Education) — "Terms such as ‘behavioural surplus’, ‘prediction products’, ‘behavioural futures markets’, and ‘instrumentarian power’ provide a useful critical language for decoding what surveillance capitalism is, what it does, and at what cost."

- Facebook, Libra, and the Long Game (Stratechery) — "Certainly Facebook’s audacity and ambition should not be underestimated, and the company’s network is the biggest reason to believe Libra will work; Facebook’s brand is the biggest reason to believe it will not."

- The Pixar Theory (Jon Negroni) — "Every Pixar movie is connected. I explain how, and possibly why."

- Mario Royale (Kottke.org) — "Mario Royale (now renamed DMCA Royale to skirt around Nintendo’s intellectual property rights) is a battle royale game based on Super Mario Bros in which you compete against 74 other players to finish four levels in the top three. "

- Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think (The Atlantic) — "In The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50, Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution scholar and an Atlantic contributing editor, reviews the strong evidence suggesting that the happiness of most adults declines through their 30s and 40s, then bottoms out in their early 50s."

- What Happens When Your Kids Develop Their Own Gaming Taste (Kotaku) — "It’s rewarding too, though, to see your kids forging their own path. I feel the same way when I watch my stepson dominate a round of Fortnite as I probably would if he were amazing at rugby: slightly baffled, but nonetheless proud."

- Whence the value of open? (Half an Hour) — "We will find, over time and as a society, that just as there is a sweet spot for connectivity, there is a sweet spot for openness. And that point where be where the default for openness meets the push-back from people on the basis of other values such as autonomy, diversity and interactivity. And where, exactly, this sweet spot is, needs to be defined by the community, and achieved as a consensus."

- How to Be Resilient in the Face of Harsh Criticism (HBR) — "Here are four steps you can try the next time harsh feedback catches you off-guard. I’ve organized them into an easy-to-remember acronym — CURE — to help you put these lessons in practice even when you’re under stress."

- Fans Are Better Than Tech at Organizing Information Online (WIRED) — "Tagging systems are a way of imposing order on the real world, and the world doesn't just stop moving and changing once you've got your nice categories set up."

- Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion.

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job.

- Reduced professional efficacy.

- Your Kids Think You’re Addicted to Your Phone (The New York Times) — "Most parents worry that their kids are addicted to the devices, but about four in 10 teenagers have the same concern about their parents."

- Why the truth about our sugar intake isn't as bad as we are told (New Scientist) — "In fact, the UK government 'Family food datasets', which have detailed UK household food and drink expenditure since 1974, show there has been a 79 per cent decline in the use of sugar since 1974 – not just of table sugar, but also jams, syrups and honey."

- Can We Live Longer But Stay Younger? (The New Yorker) — "Where fifty years ago it was taken for granted that the problem of age was a problem of the inevitable running down of everything, entropy working its worst, now many researchers are inclined to think that the problem is “epigenetic”: it’s a problem in reading the information—the genetic code—in the cells."

- Be thorough and excellent in everything that you do

- Be smart and funny

- Be disarmingly honest

- Work without division of any kind

- Practise servant leadership

- People Who Claim to Work 75-Hour Weeks Usually Only Work About 50 Hours (New York Magazine) — "People overestimate how often they do all sorts of things they “ought” to be doing, often by even larger margins than with work for pay."

- Employee privacy in the US is at stake as corporate surveillance technology monitors workers’ every move (CNBC) — "In the workplace, almost any consumer privacy law can be waived. Even if companies give employees a choice about whether or not they want to participate, it’s not hard to force employees to agree."

- Workers Should Be in Charge (Jacobin) — "Every day, private equity companies snatch up firms and strip them dry. But there’s an alternative: allow workers to buy their workplace and run it themselves."

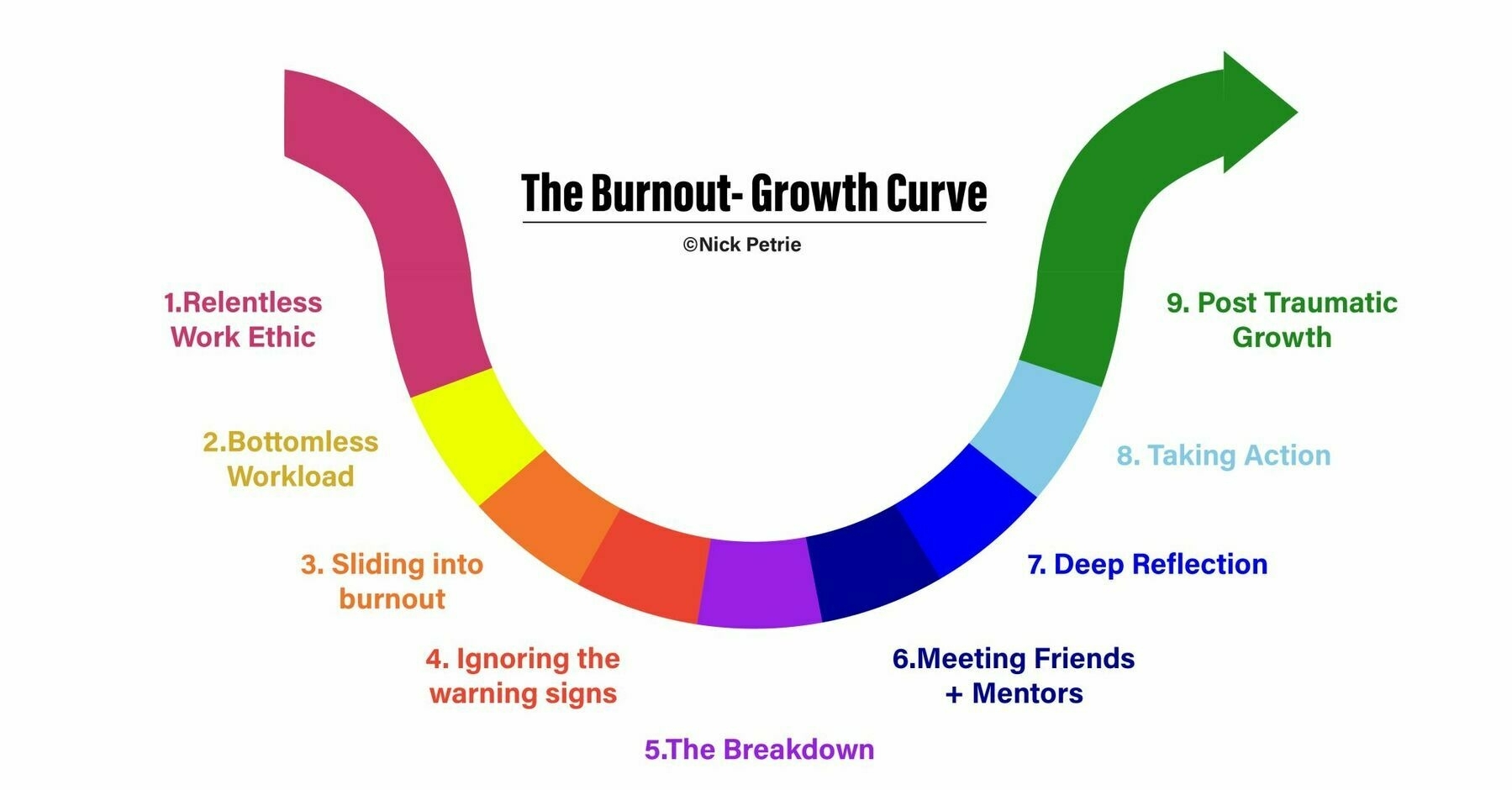

The burnout curve

I stumbled across this on LinkedIn. There doesn't seem to be an authoritative source yet other than the author's (Nick Petrie) social media posts, which is a shame. So I'm quoting most of it here so I can find and refer to it in future.

In terms of my own experience, I slid down that slope pretty quickly in my teaching career, and definitely experienced the 'trap' of going back into a similar situation in a different school. It was also toxic as I had been promoted quickly and, looking back, probably beyond my abilities and experience at the time.

But the great thing about this graphic is that it shows that it's possible to dig your way out, as I did, by realising that a different path is possible. It hasn't always been plain sailing, and there have been other, lesser, traumas since. But I've definitely grown from my earlier experiences, and this is a handy chart to show people who are near the bottom of the curve.

When we interviewed people who had burned out, they told us remarkably similar stories.1. A relentless work ethic – they had a set of beliefs and stories that drove them to work hard - I will deliver, I won’t let people down, I must give 100% at all times.2. Bottomless workload – they joined organizations that rewarded their work ethic with endless work. The harder they worked the more they were given.3. Sliding into burnout – thoughts of work became constant. They had trouble switching off in the evenings, work was taking over their life.4. Ignoring the warning signs – their body was sending signals that something needed to change. They were tense, irritated, exhausted. But they couldn’t slow down – there was too much to do.5. The breakdown – For those who would not listen, the body and brain had a last resort. They shut down. People couldn’t get out of bed, couldn’t drive, couldn’t read. The body refused to go on.The trap for many people is the belief that rest is the solution. So, they took a break – a week, a month or a year. They then went back to the same work, with the same mindset and the same behaviors. They got the same result.The people we interviewed who genuinely overcame burnout followed a common path.6. Meeting friends and mentors – they realized they couldn’t repeat their past. They needed new perspectives and a new approach. They got these from family, peers, coaches, therapists and support groups.7. Deep reflection – they came off autopilot for the first time in years. They reflected deeply on the past – what caused me to burnout? What was driving me? Then the future – what sort of work and life do I want going forward? How can I move myself towards this vision?8. Taking action – they took new actions, sometimes big – change of job, change of career - sometimes small - they set new boundaries, restarted a hobby, got a therapist. Some things helped, some things did not. It didn’t matter. The key thing was they were doing NEW things. They were not repeating their old habits. New actions led to new insights and habits.9. Post traumatic growth – when we interviewed people who took this path 2 years after their burnout, the most surprising thing was how much they had grown from the experience.

Source: Nick Petrie | LinkedIn

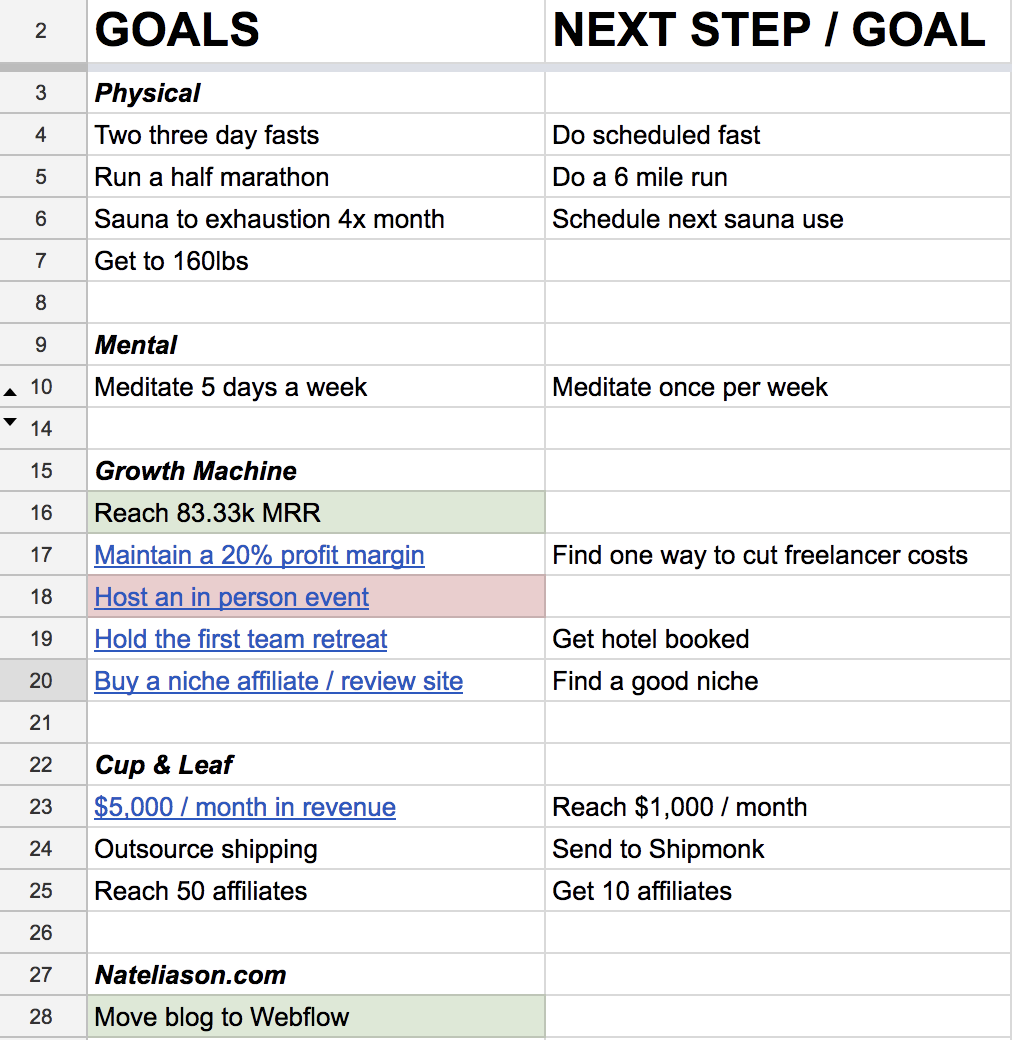

The life run by spreadsheet is not worth living

When work is the most significant thing in your life, you optimise for it. When relationships are are the most significant things in your life, you optimise for those.

I find this post by ‘crypto engineer’ Nat Eliason a bit tragic, to be honest. He says he’s almost always working, there’s zero mention of family, and he says that all of his friends are people who are hustling too.

As Socrates didn’t say, “the life run by spreadsheet is not worth living”.

Here’s the biggest thing to keep in mind when you’re reading about my process:Source: How to Be Really, Really, Ridiculously Productive | Nat EliasonI’m almost always working.

This is not some Tim Ferrissian “here’s how to work 2 hours a day and make lots of money” post. I tried that. It sucks. You’ll get depressed in about two days if you have an ounce of ambition in you. If you’re trying to optimize around working less, find better work.

It doesn’t mean, though, that I’m always doing things that feel like work. It means I enjoy the work that I do, and I’ve found ways to make my hobbies productive.

The burnout epidemic

I work an average of about 25 hours per week and I’m tired at the end of it. I can’t even imagine how I coped in my twenties while teaching.

Textile mill workers in Manchester, England, or Lowell, Massachusetts, two centuries ago worked for longer hours than the typical British or American worker today, and they did so in dangerous conditions. They were exhausted, but they did not have the 21st-century psychological condition we call burnout, because they did not believe their work was the path to self-actualization. The ideal that motivates us to work to the point of burnout is the promise that if you work hard, you will live a good life: not just a life of material comfort, but a life of social dignity, moral character and spiritual purpose.Source: Your work is not your god: welcome to the age of the burnout epidemic | The Guardian[…]

This promise, however, is mostly false. It’s what the philosopher Plato called a “noble lie”, a myth that justifies the fundamental arrangement of society. Plato taught that if people didn’t believe the lie, then society would fall into chaos. And one particular noble lie gets us to believe in the value of hard work. We labor for our bosses’ profit, but convince ourselves we’re attaining the highest good. We hope the job will deliver on its promise, and hope gets us to put in the extra hours, take on the extra project and live with the lack of a raise or the recognition we need.

Productivity dysmorphia

This is a useful term for “the intersection of burnout, imposter syndrome, and anxiety”.

Say you manage a coffee shop. In one day, you placed all the orders with your vendors, cleaned all the machines, launched a new promotional push, scheduled your employees’ shifts for the following month, and responded to every review and email. In this hypothetical scenario, you did great! You got all those tasks done and were attentive to your employees’ needs for time off and fair schedules. So why do you still feel like you didn’t do enough and you’re failing? Productivity dysmorphia.Source: How to Overcome ‘Productivity Dysmorphia’ | Lifehacker[…]

Productivity dysmorphia can impact you outside of your job, too. Say you were aiming for a seven-day streak on your Peloton, but you were too tired or had too much work to do on that last day. You might feel like you are a failure for not working out that day, but that just isn’t true. You worked out the six days before that. Missing one goal doesn’t invalidate everything else you’ve done up until that point. We all get overwhelmed and overworked.

Try to reconsider what you think of as “productivity.” It’s productive to get all your work done, yes, and productive to work out or devote a certain amount of time every night to your side job or hobby. It’s also productive to rest. Relaxing and refreshing your mind and body will enable you to accomplish more in the near future without risking the dreaded burnout. Celebrate everything you do as a step toward productivity. Write down your rest periods, too. They count.

Psychological hibernation

I can’t really remember what life was like before having children. Becoming a parent changes you in ways you can’t describe to non-parents.

Similarly, if we tried to go back in time and explain how the pandemic has changed us, how we’re more susceptible to burnout, less up for meeting with other people, it would be almost impossible to do.

One term that might be useful, however, is ‘psychological hibernation’ — as this article explains.

Was it always like this? Can anyone actually remember what it was like before? For some reason, coming up with an answer to that question is like recalling a boring dream: the more you attempt to remember the details of life before Covid, the quicker it fades, as if it never happened at all.Source: The great Covid social burnout: why are we so exhausted? | New StatesmanIn 2018, a group of psychologists in the Antarctic published a report that may help us understand our current collective exhaustion. The researchers found that the emotional capacity of people who had relocated to the end of the world had been significantly reduced in the time they had been there; participants living in the Antarctic reported feeling duller than usual and less lively. They called this condition “psychological hibernation”. And it’s something many of us will be able to relate to now.

“One of the things that we noticed throughout the pandemic is that people started to enter this phase of psychological hibernation,” said Emma Kavanagh, a psychologist specialising in how people deal with the aftermath of disasters. “Where there’s not many sounds or people or different experiences, it doesn’t require the brain to work at quite the same level. So what you find is that people felt emotionally like everything had just been dialled back. It looks a lot like burnout, symptom wise.” Kavanagh continued: “I think that happened to us all in lockdown, and we are now struggling to adapt to higher levels of stimulus.”

Six Causes of Burnout at Work

This is an interesting article from UC Berkley’s Greater Good Magazine based on journalist Jennifer Moss' new book The Burnout Epidemic: The Rise of Chronic Stress and How We Can Fix It. It not only talks about organisational factors, but personality types as well.

1. Workload. Overwork is a main cause of burnout. Working too many hours is responsible for the deaths of millions of people every year, likely because overwork makes people suffer weight loss, body pain, exhaustion, high levels of cortisol, sleep loss, and more.Source: Six Causes of Burnout at Work | Greater Good2. Perceived lack of control. Studies show that autonomy at work is important for well-being, and being micromanaged is particularly de-motivating to employees. Yet many employers fall back on watching their employees’ every move, controlling their work schedule, or punishing them for missteps.

3. Lack of reward or recognition. Paying someone what they are worth is an important way to reward them for their work. But so is communicating to people that their efforts matter.

4. Poor relationships. Having a sense of belonging is necessary for mental health and well-being. This is true at work as much as it is in life. When people feel part of a community, they are more likely to thrive. As a Gallup poll found, having social connections at work is important. “Employees who have best friends at work identify significantly higher levels of healthy stress management, even though they experience the same levels of stress,” the authors write.

5. Lack of fairness. Unfair treatment includes “bias, favoritism, mistreatment by a coworker or supervisor, and unfair compensation and/or corporate policies,” writes Moss. When people are being treated unjustly, they are likely to burn out and need more sick time.

6. Values mismatch. “Hiring someone whose values and goals do not align with the values and goals of the organization’s culture may result in lower job satisfaction and negatively impact mental health,” writes Moss. It’s likely that someone who doesn’t share in the organization’s mission will be unhappy and unproductive, too.

Health and sanity before profit

This is an interesting article that takes the tennis player Naomi Osaka’s withdrawal from the French Open as a symptom of wider trends in the workplace.

Many Americans have experienced burnout, and its adjacent phenomenon, languishing, during the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, it has hit women, especially mothers, particularly hard and women’s professional ambition has suffered, according to a survey by CNBC/SurveyMonkey. This trend might be read as a grim step backward in the march toward gender egalitarianism. Or, as in some of the criticism of Ms. Osaka, as an indictment of younger generations’ work ethic. Either interpretation would be misguided.Source: Naomi Osaka and the Cost of Ambition | The New York TimesA better way of putting it: Ms. Osaka has given a public face to a growing, and long overdue, revolt. Like so many other women, the tennis prodigy has recognized that she has the right to put her health and sanity above the unending demands imposed by those who stand to profit from her labors. In doing so, Ms. Osaka exposes a foundational lie in how high-achieving women are taught to view their careers.

In a society that prizes individual achievement above most other things, ambition is often framed as an unambiguous virtue, akin to hard work or tenacity. But the pursuit of power and influence is, to some extent, a vote of confidence in the profit-driven myth of meritocracy that has betrayed millions of American women through the course of the pandemic and before it, to our disillusionment and despair.

How to recover from burnout

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines occupational burnout as "feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job; and reduced professional efficacy."

Based on that definition, I've experienced burnout twice, once in my twenties and once in my thirties. But what to do about it? And how can we prevent it?

I read a lot of Hacker News, including some of the 'Ask HN' threads. This one soliciting advice about burnout received what I considered to be a great response from one user.

Around August last year I just couldn't continue. I wasn't sleeping, I was frequently run down, and I was self-medicating more and more with drugs and alcohol. It eventually got to the point where simply opening my laptop would elicit a fight or flight response.

I was lucky enough to be in a secure enough financial situation to largely take 6 months off. If you're in a position to do this, I highly recommend it.

I uninstalled gmail, slack, etc. from my phone. I considered getting a dumb phone, but settled for turning off push notifications for everything instead. I went away with my girlfriend for a week and left all my tech at home except for my kindle (literally the first time I've been disconnected for more than a couple of days in probably 20 years). I exercised as much as possible and spent time in nature going for walks, etc.

I've been back at it part time for the last few months. Gradually I felt the feelings of burnout being replaced with feelings of boredom, which is hopefully my brain's way of saying that it's starting to repair itself and ready to slowly return to work.

I'm still nowhere near back to peak productivity, but I'm starting to come to terms with the fact that I may never get back there. I'm 36 and probably would have dropped dead of overwork by 50 if I kept up the tempo of the last 10 years anyway.

I'm not 'cured' by any means, but I believe things are slowly getting better.

My advice to you is to be kind and patient with yourself. Try not to stress about not having a side-project, and instead just focus on self-care for a while. Someone posted this on HN a few weeks back and it really hit close to home for me: http://www.robinhobb.com/blog/posts/38429

Friday feeds

These things caught my eye this week:

Header image via Dilbert

Situations can be described but not given names

So said that most enigmatic of philosophers, Ludwig Wittgenstein. Today's article is about the effect of external stimulants on us as human beings, whether or not we can adequately name them.

Let's start with music, one of my favourite things in all the world. If the word 'passionate' hadn't been devalued from rampant overuse, I'd say that I'm passionate about music. One of the reasons is because it produces such a dramatic physiological response in me; my hairs stand on end and I get a surge of endophins — especially if I'm also running.

That's why Greg Evans' piece for The Independent makes me feel quite special. He reports on (admittedly small-scale) academic research which shows that some people really do feel music differently to others:

Matthew Sachs a former undergraduate at Harvard, last year studied individuals who get chills from music to see how this feeling was triggered.

The research examined 20 students, 10 of which admitted to experiencing the aforementioned feelings in relation to music and 10 that didn't and took brain scans of all of them all.

He discovered that those that had managed to make the emotional and physical attachment to music actually have different brain structures than those that don't.

The research showed that they tended to have a denser volume of fibres that connect their auditory cortex and areas that process emotions, meaning the two can communicate better.

Greg Evans

This totally makes sense to me. I'm extremely emotionally invested in almost everything I do, especially my work. For example, I find it almost unbearably difficult to work on something that I don't agree with or think is important.

The trouble with this, of course, and for people like me, is that unless we're careful we're much more likely to become 'burned out' by our work. Nate Swanner reports for Dice that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has recently recognised burnout as a legitimate medical syndrome:

The actual definition is difficult to pin down, but the WHO defines burnout by these three markers:

Interestingly enough, the actual description of burnout asks that all three of the above criteria be met. You can’t be really happy and not producing at work; that’s not burnout.

As the article suggests, now burnout is a recognised medical term, we now face the prospect of employers being liable for causing an environment that causes burnout in their employees. It will no longer, hopefully, be a badge of honour to have burned yourself out for the sake of a venture capital-backed startup.

Having experienced burnout in my twenties, the road to recovery can take a while, and it has an effect on the people around you. You have to replace negative thoughts and habits with new ones. I ultimately ended up moving both house and sectors to get over it.

As Jason Fried notes on Signal v. Noise, we humans always form habits:

When we talk about habits, we generally talk about learning good habits. Or forming good habits. Both of these outcomes suggest we can end up with the habits we want. And technically we can! But most of the habits we have are habits we ended up with after years of unconscious behavior. They’re not intentional. They’ve been planting deep roots under the surface, sight unseen. Fertilized, watered, and well-fed by recurring behavior. Trying to pull that habit out of the ground later is going to be incredibly difficult. Your grip has to be better than its grip, and it rarely is.

Jason Fried

This is a great analogy. It's easy for weeds to grow in the garden of our mind. If we're not careful, as Fried points out, these can be extremely difficult to get rid of once established. That's why, as I've discussed before, tracking one's habits is itself a good habit to get into.

Over a decade ago, a couple of years after suffering from burnout, I wrote a post outlining what I rather grandly called The Vortex of Uncompetence. Let's just say that, if you recognise yourself in any of what I write in that post, it's time to get out. And quickly.

Also check out:

Culture eats strategy for breakfast

The title of this post is a quotation from management consultant, educator, and author Peter Drucker. Having worked in a variety of organisations, I can attest to its truth.

That's why, when someone shared this post by Grace Krause, which is basically a poem about work culture, I paid attention. Entitled Appropriate Channels, here's a flavour:

We would like to remind you all

That we care deeply

About our staff and our students

And in no way do we wish to silence criticism

But please make use of the

Appropriate ChannelsThe Appropriate Channel is tears cried at home

And not in the workplace

Please refrain from crying at your desk

As it might lower the productivity of your colleagues

Organisational culture is difficult because of the patriarchy. I selected this part of the poem, as I've come to realise just how problematic it is to let people know (through words, actions, or policies) that it's not OK to cry at work. If we're to bring our full selves to work, then emotion is part of it.

Any organisation has a culture, and that culture can be changed, for better or for worse. Restaurants are notoriously toxic places to work, which is why this article in Quartz, is interesting:

Since four-time James Beard award winner Gabrielle Hamilton opened Prune’s doors in 1999, she, along with her co-chef Ashley Merriman, have established a set of principles that help guide employees at the restaurant. According to Hamilton and Merriman, the code has a kind of transformative power. It’s helped the kitchen avoid becoming a hierarchical, top-down fiefdom—a concentration of power that innumerable chefs have abused in the past. It can turn obnoxious, entitled patrons into polite diners who are delighted to have a seat at the table. And it’s created the kind of environment where Hamilton and Merriman, along with their staff, want to spend much of their day.

The five core values of their restaurant, which I think you could apply to any organisation, are:

We live in the 'age of burnout', according to another article in Quartz, but there's no reason why we can't love the work we do. It's all about finding the meaning behind the stuff we get done on a daily basis:

Our freedom to make meaning is both a blessing and a curse. To get somewhat existential about it, “work,” and the problems associated with it as an amorphous whole, do not exist: For the individual, only his or her work exists, and the individual is in control of that, with the very real power radically to change the situation. You could start the process of changing your job right now, today. Yes, arguments about the practicality of that choice well up fast and high. Yes, you would have to find another way to pay the bills. That doesn’t negate the fact that, fundamentally, you are free.

It's important to remember this, that we choose to do the work we do, that we don't have to work for a single employer, and that we can tell a different story about ourselves at any point we choose. It might not be easy, but it's certainly doable.

Also check out: