2024

- Hope is dehumanising because it turns people away from this world.

- Hope is a desire for some predetermined future outcome.

- Hope takes us out of the present moment.

- Hope is passive.

- Hope exists alongside evil.

- Natality is the principle of humanity.

- Natality is the promise of new beginnings.

- Natality is present in the Now.

- Natality is the root of action.

- Natality is the miracle of birth.

Barnacle ball

Some great photos in this year’s British Wildlife Photography Awards. I was going to share the black and white one of the mountains, but this one, the overall winner, is incredibly powerful. It’s also just a fantastically-composed image.

An incredible image of a football covered in goose barnacles is the winner of this year’s British Wildlife Photography Awards.

The picture was chosen from more than 14,000 entries by both amateur and professional photographers.

The photograph, which also won the Coast and Marine category, was taken by Ryan Stalker.

“Above the water is just a football. But below the waterline is a colony of creatures. The football was washed up in Dorset after making a huge ocean journey across the Atlantic,” says Stalker.

“More rubbish in the sea could increase the risk of more creatures making it to our shores and becoming invasive species.”

Source: BBC News

Anti-AI hyperbole

This post has been going around my networks recently, so I’ve finally got around to giving it a read. The first thing that’s worth pointing out is that the author, Ed Zitron, is CEO of a tech PR firm. So it’s no surprise that it’s written in a way that’s supposed to try and pop the AI hype bubble.

I’m not unsympathetic to Zitron’s position, but when he talks about not knowing anyone using ChatGPT, I don’t think he’s telling the truth. I’m using GPT-4 every day at this point, and now supplementing it with Perplexity.ai and Claude 3. A combination of the three can be really useful for everything from speeding up idea generation to converting a bullet point list to a mindmap.

One thing I’ve found AI assistants to be incredibly powerful for is to spot things I might have missed, to provide a different perspective. Or even to put in a list of things and to generate recommendations based on that. You can do this for music playlists through to business competitors.

Every time Sam Altman speaks he almost immediately veers into the world of fan fiction, talking about both the general things that “AI” could do and non-specifically where ChatGPT might or might not fit into that without ever describing a real-world use case. And he’s done so in exactly the same way for years, failing to describe any industrial or societal need for artificial intelligence beyond a vague promise of automation and “models” that will be able to do stuff that humans can, even though OpenAI’s models continually prove themselves unable to match even the dumbest human beings alive.

Altman wants to talk about the big, sexy stories of Average General Intelligences that can take human jobs because the reality of OpenAI — and generative AI by extension — is far more boring, limited and expensive than he’d like you to know.

[…]

I believe a large part of the artificial intelligence boom is hot air, pumped through a combination of executive bullshitting and a compliant media that will gladly write stories imagining what AI can do rather than focus on what it’s actually doing. Notorious boss-advocate Chip Cutter of the Wall Street Journal wrote a piece last week about how AI is being integrated in the office, spending most of the article discussing how companies “might” use tech before digressing that every company he spoke to was using these tools experimentally and that they kept making mistakes.

[…]

Generative AI’s core problems — its hallucinations, its massive energy and unprofitable compute demands — are not close to being solved. Having now read and listened to a great deal of Murati and Altman’s interviews, I can find few cases where they’re even asked about these problems, let alone ones where they provide a cogent answer.

And I believe it’s because there isn’t one.

Source: Where’s Your Ed At?

Microcast #103 — Microphones and Moving to Micro.blog

The first microcast of 2024 and also the first on micro.blog. This one discusses the reasons for the move, and how it went.

Show notes

Taking seriously the noise and free-floating anxiety

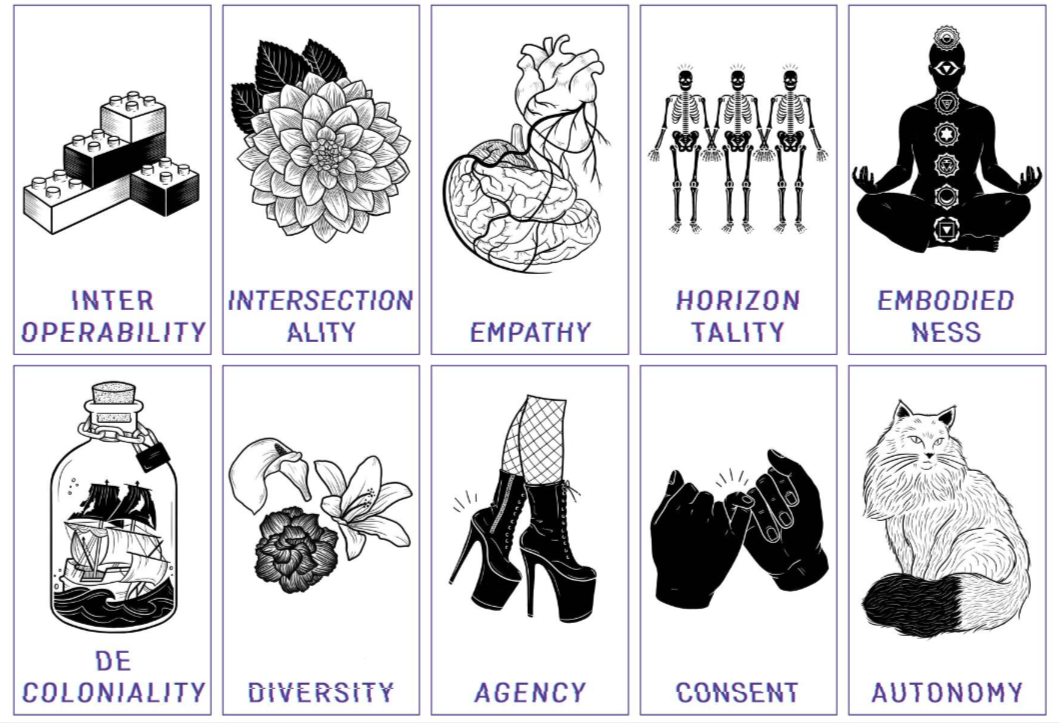

I’ve always enjoyed Helen Beetham’s writing, and her more recent work on AI has filled a gap for me after Audrey Watters shifted gears. With this post, I’m most interested in the ending, in which Helen reflects on how much time it takes to refute the bullshit.

She links to notmy.ai which outlines why AI is a feminist issue (clue: patriarchal by design, embedded racism, precarious labour).

[W]hen I started a blog about critical approaches to technology in education, I never imagined that generative AI would fill my own horizon. It has not been entirely fun. A colleague recently described it to me as ‘the constant intellectual labour involved in having to take seriously the noise and free-floating anxiety’, and that labour feels increasingly pointless. Talking ‘AI’ down is still talking about AI, it still adds to the vortex of attention. There are other many more important things in the world to be anxious about (though ‘AI’ seems set to make all of them worse).

AI will probably give paying users a new interface on their work and play that will be fun for a while, and then invisible - part of an ever-more-immersive life online. When ROI falters there will be another story (or a newer, better, ‘smarter’ version of the AI story) to sell hyper-productivity and automation to businesses, and to keep driving capital towards the biggest platforms. I just keep thinking that the idea all this has something to do with knowledge or learning is so obviously detrimental to education, and so obviously stupid and wrong, that education will find a way of talking back. Or - because alternative stories are available - will tell these stories confidently, so I can think about something else.

Source: imperfect offerings

Austerity is not efficiency

The UK is currently limping towards a General Election which, although it hasn’t been called yet, will probably be in October 2024. The past 14 years have absolutely decimated my country, with cuts to public services, a massive loss of trust in public officials, and spiraling inequality. The costs of Brexit cannot even be put into meaningful terms.

This article in The Guardian talks about the impact of Tory cuts to English councils, meaning that they have had to cut services. Some councils, either through bad luck, incompetence, or both, are in a really bad way. I wonder how much this will affect internal migration in the UK, as up here in Northumberland the NHS performs well, our bins are collected regularly, and the quality of life (I would say) is better.

Most of us now know the basics. In 2023, Birmingham city council – which is controlled by Labour, and is reckoned to be Europe’s largest local authority – effectively went bankrupt. There were three key reasons: massive cuts in funding from Whitehall, the cost of the belated resolution of the council’s gender pay gap, and the mind-boggling mishandling of a new IT system. In the midst of the rising need for council services – much of which was rooted in all the dislocation and disaster of the Covid crisis – all this spelled disaster. Now, many of the city’s services must be either hacked down or done away with, in pursuit of savings of about £300m over two years. As far as anyone understands it, this is the deepest programme of local cuts ever put through by a UK council.

[…]

Birmingham may be an outlier, but comparable stories are playing out all over England: in Nottingham, Somerset, Hampshire, Leicester, Bradford, Southampton and more. The House of Commons levelling up, housing and communities select committee puts English councils’ current financial gap at about £4bn a year, which could have been filled more than twice over by the money Jeremy Hunt used for that almost meaningless cut in national insurance. He seems to still think that councils must sink or swim: even more depressingly, he and his allies in the rightwing press have reprised old and stupid rhetoric about millions supposedly being wasted on “consultants” and “diversity schemes”.

[…]

Continuing austerity does not just kill people’s services; it has long since warped most political debates about what we should expect from the state. In lots of places, squalor, mess and festering social problems are now seen as the norm. So too is a scepticism about people’s need for help, which is endlessly encouraged by politicians and people in the media. That absurd opportunist Lee Anderson made his name by claiming that food banks were “abused” by people who didn’t need them. Now, the Times columnist Matthew Parris claims to “not believe in ADHD at all” and says that autism is “a much abused diagnosis”, while other voices insist that parents whose disabled children get some dependable help from their local councils are the possessors of “a golden ticket”. In both cases, the insidious process is much the same. First, services fail. Then, casting doubt on the resulting pain and letting the people responsible off the hook, there are loud suggestions that levels of need may not have been that great in the first place. As a result, austerity can be recast as efficiency, a move that always appeals to politicians, of whatever party.

Source: The Guardian

Reframing as small i's

This is such an important reframing. I, for one, definitely have a tendency to let my latest success, failure, or injury define me. It ends up being a bit of a rollercoaster.

“I am such a loser, I can’t even do >insert attempt here< “. This creates an overblown sense of guilt (and self-pity), robbing us of any empowerment that might be had and tends to leave us moping in a corner somewhere. The ‘Big I, Small I’ visual gives us a perspective check. The Big I represents you as the shiny complex structure that is you altogether, while the Small I’s each represent one aspect of you. Every small I (for example: you trying to reach a deadline with good quality content) is one of many small I’s. It is part of you and therefore not to be trifled with but it does not define you. You are not this one thing that you are trying to achieve, you are many.

Source: Priscilla Haring

Image: DALL-E 3

Scaling AI requires 'muddling through'

The always thought-provoking Venkatesh Rao poses the question of what kind of scaling we need for AI. His analogy with building skyscrapers out of bricks-and-mortar is an interesting one. It’s a long read, but worth it.

The part which really resonated with me is when Rao starts talking about governance for AI agents, which needs to be in the form of liberal democracy rather than autocracy. “Regulating [AIs] will look like economic regulation, not technology regulation” he says.This is why you need people who can think philosophically about technology and the future of humanity.

Fascinating.

To keep AI evolving, we need the various heterodoxies to cohere into one or more alternative positive visions of how to build the technology itself, not just creative reframes that make for stimulating cocktail party conversations. Into one or more new idea of what sort of AI we should attempt to built, in an engineering rather than ethical sense of should. As in well-posed, architecturally sound, and conceptually elegant enough to handle whatever we choose to throw at it.

I’m asking the question in the same sense as one might ask, how should we attempt to build 2,500 foot skyscrapers? With brick and mortar or reinforced concrete? The answer is clearly reinforced concrete. Brick and mortar construction simply does not scale to those heights. Culture wars in architecture and urbanism around whether or not skyscrapers are a good idea for society are moot unless you have good options for actually building them.

[…]

The current idea seems to be: If we build AI datacenters that are 10x or 100x the scale of todays (as Sam Altman appears to want to), and train GPT-style models on them that are also correspondingly scaled up, we’ll get to the most interesting sorts of AI. This is like trying to build the Burj Khalifa out of brick-and-mortar. It’s a fundamentally unsound idea. Problems of data movement and memory management at scale that are already cripplingly hard will become insurmountable. Just as the very idea of a 2,500 foot high brick structure is unsound because bricks don’t have the right structural properties, the current “bricks” of modern AI (to a first approximation, the “naked” Large X Models thinly wrapped in application logic) are the wrong ones.

[…]

[Going] back to the analogy to reinforced concrete. [The AIs Rao is arguing for] are fundamentally built out of composite materials that combine the constituent simple materials in very deliberate ways to achieve particular properties. Reinforced concrete achieves this by combining rebar and cement in particular geometries. The result is a flexible language of differentiated forms (not just cuboidal beams) with a defined grammar.

[They] will achieve this by combining embodiment, boundary management, temporality, and personhood elements in very deliberate ways, to create a similar language of differentiated forms that interact with a defined grammar.

Source: Ribbonfarm

Born to run

I set myself the target of running 1,000km this year. Camille Herron just ran 900km in six days 🤯

When the FURTHER event started last Wednesday, Herron was already the holder of multiple world records from 50 to 250 miles. A small crowd gathered under four towers of stage lights and rows of orange and white tents. The 42-year-old was in shades, a water bottle stuffed in the crotch of her shorts. On day one, she chugged a Coke float and ran 133 miles. Day two, she downed tacos and added another 113 miles. On 8 March International Women’s Day, she broke the American 48-hour road record for women. More would follow.

Each time Herron broke a record, she held her arms out wide, her hands pointing to the sky as if to say, “isn’t this incredible?” The fact that she is openly awed by what she does has at times made her a target in the ultrarunning community. Her whimsical pre-race mantra of “letting the magic come out” only adds to that. But it’s hard to argue with the numbers. And the numbers and records were piling up: a new 300km mark, the American 48-hour road record, a new 300-mile road record, the women’s 500km world record, the women’s 500 mile. When she completed the latter, she danced around the start line in pink compression socks, celebrating with high fives and hugs.

[…]

But Herron isn’t done. As the sun rises over the Santa Rosa Mountains, she lifts herself to her feet once more. One more push. One more loop, then two, three. She reaches 900km, another record, then it’s over. In her wake are 11 world records recognized by GOMU and a world best performance by the IAU. Either way, the numbers on the LED screen read a clear 560.3 miles. Above is one word in all caps: FURTHER.

Source: The Guardian

Consciousness porn

Sometimes, I come across a post which comes from leftfield and is almost impossible to quote in a meaningful way. This one revolves around three things I’ve never even heard of, let alone experienced. The author puts them under the heading ‘consciousness porn’, with the three examples being quite diverse.

What I find so fascinating is that there are layers upon layers to this. For example, one of the commenters points out that the guy shooting the long videos of walks around Tokyo posted to his YouTube channel that he was depressed, wasn’t going to do any more after uploading the ones he’d already recorded, and didn’t know why anyone watched them in the first place.

It took me a while to comprehend why my son would watch other people play videogames. After a while I began to understand that there was an element of learning how to improve his own gameplay, but there was also an aesthetic to it. This consciousness porn seems to be almost pure aesthetic. I guess the next stage is endless versions of this created using AI.

Rambalac does everything he can to avoid intruding on the world he is observing, to be, like the character in Christopher Isherwood’s novel Goodbye to Berlin, “a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.” But occasionally we catch a glimpse of his reflection in a store window or elevator mirror – oh, he’s not Japanese! And in every frame we feel his presence – quiet, sweet, and a little sad, stopping to watch a black cat thread its way across a cluttered stoop, showing us the label of the green tea he’s bought from a vending machine, looking away politely from a fellow pedestrian, or standing still, on a rainy night, before the red gate that marks the entrance to a Shinto shrine, entranced.

[…]

I often listen to dub techno while watching Rambalac videos, which amplifies their chill, phenomenological trippiness, and makes me feel like I’m experiencing a mutant artform invented by William Gibson. An artform I call consciousness porn.

Source: Donkeyspace

Image: DALL-E 3

Vendor lock-in writ large

People call me prolific, but I’m nothing compared to Cory Doctorow. I can’t keep up with his mostly-daily newsletters, never mind his longer-form stuff.

In this piece, he talks about one of his favourite topics: vendor lock-in. However, the genius lies in the way that he explains, in a way that sounds so obvious that it feels like scales falling from your eyes, why people blame immigrants for the lack of jobs. The real, historical reason for the decline in good jobs is because employers (with government help) smashed the unions.

Moving onto AI, he points out the “monstrous proposition” of AI companies who suggest that their clients train models based on workers, then fire the workers, replacing them with the AI products. The latter are nowhere near good enough to actually do the workers' jobs, but all the AI companies need to do is sell the proposition.

That’s why there’s no jobs around at the moment: an illusion based on VC money. Remember how Uber was going to mean self-driving cars and the end of public transport? Remember how cryptocurrencies were going to mean the end of banks? Here we go again.

Bruce Schneier coined the term “feudal security” to describe Big Tech’s offer: “move into my fortress – lock yourself into my technology – and I will keep you safe from all the marauders roaming the land”

It’s a tried-and-true bullying tactic: convince your victim that only you can keep them safe so they surrender their agency to you, so the victim comes under your power and can’t escape your cruelty and exploitation. The focus on external threats is key: so long as the victim is more afraid of the dangers beyond the bully’s cage than they are of the bully, they can be lured deeper and deeper until the cage-door slams shut.

But here’s the thing about trusting a warlord when he tells you that the fortress’s walls are there to keep the bad guys out: those walls also keep you in. Sure, Apple will use its control over Ios to stop Facebook from spying on you, but when Apple spies on you, no one can help you, because Apple exercises total control over all Ios programs, including any that would stop Apple from nonconsensually harvesting your data and selling access to it:

Source: Pluralistic

Be careful what you wish for

I’ve already posted a thread about this on the Fediverse, so I’ll just copy-and-paste then tweak from that rant. TL;DR: Adobe have published a (commissioned) report about digital credentials, everyone’s over-excited, and I want to sound a note of caution.

About 15 years ago, it was clear that Higher Education was about to become significantly ‘unbundled’ in western countries. The trend had started even before the start of my career, but accelerated around that time. We had things like Pearson being given degree-awarding powers, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) allowing anyone to join university-provided courses, and the first blushes of digital credentials.

As thinkers such as Audrey Watters pointed out, unbundling is all well and good, but you better be damned careful about who’s doing the ‘rebundling’ and for what purpose. So, of course, the MOOC providers turned into non-profit and for-profit providers that met with various success (edX, Udacity, FutureLearn, etc.) These all needed ways to ‘certify’ their courses. Some partnered with universities, others went alone with their own credentialing.

The digital credentials space has always been a difficult one to keep track of. That’s because it’s decentralised by design, just like the Fediverse, and… email. So while there are absolutely standards that make the whole thing work (Open Badges, etc.) it’s always been difficult to talk about numbers and how people are using digital credentials. In true “the future is here, it’s just unevenly distributed” style, some sectors have seen explosive adoption of digital credentials.

IBM, for example, have issued millions of digital credentials for things that you wouldn’t necessarily go to university to learn. It’s a big deal, and leads to decently-paying (and often high-paying) jobs. That’s great, and I point to this a lot. But it’s not like IBM did it out the goodness of their hearts. They’re looking to remove the degree requirement for their jobs, which of course has a long-term depressing effect on wages.

Coming back to Adobe, while it’s great that they’ve suddenly discovered digital credentials and have commissioned A Report To Tell Us How Great They Are, we’d be naive to think that this is a benevolent act. What they’re doing, it seems, is positioning the ‘Adobe Certified Professional’ digital credential as the one that you need in that particular industry. That means tying ‘creativity’ to using certain tools, and having a very privatised ‘rebundling’ of knowledge and skills.

So, be careful what you wish for, I guess. Could a lot of this have been foreseen over a decade ago? Absolutely. But the problem, as many on the Fediverse will recognise, is that there’s a vested interest in not recognising the diversity of human experience. Digital credentials could and should be used to recognise lifelong and lifewide learning. They can be used to showcase the breadth of our experience in a holistic way.

That’s not what brands are interested in, though. Brands are interested in capturing and enclosing you as data points to be packaged up and sold alongside their proprietary products.

I’m sure there are plenty of people in my network (especially on LinkedIn) which will see this as an over-reaction. “But Doug, isn’t bringing more attention to the space worthwhile?” Not if the lens that is used to understand the space is reductionist and perpetuates some of the very problems we’re trying to solve.

Gone are the days of a college degree being the only key to unlock meaningful careers. Employers today need job candidates and employees with new, in-demand skills, and they expect to see them demonstrated in a variety of ways beyond a college transcript. With the rise of remote work, digital transformation, and AI, today’s most in-demand skills — creative problem-solving, visual communication, and digital fluency — are especially hard for hiring managers to identify in job application materials.

To shed light on this evolving landscape, Adobe has just released a research white paper, “The Creative Edge: How Digital Credentials Unlock Emerging Skills in the Age of AI.” Conducted by Edelman, the results of this commissioned global research study outline the role digital credentials play in helping career seekers get hired by showcasing their digital and creative skills.

Source: How digital credentials unlock emerging skills in the age of AI

Image: DALL-E 3

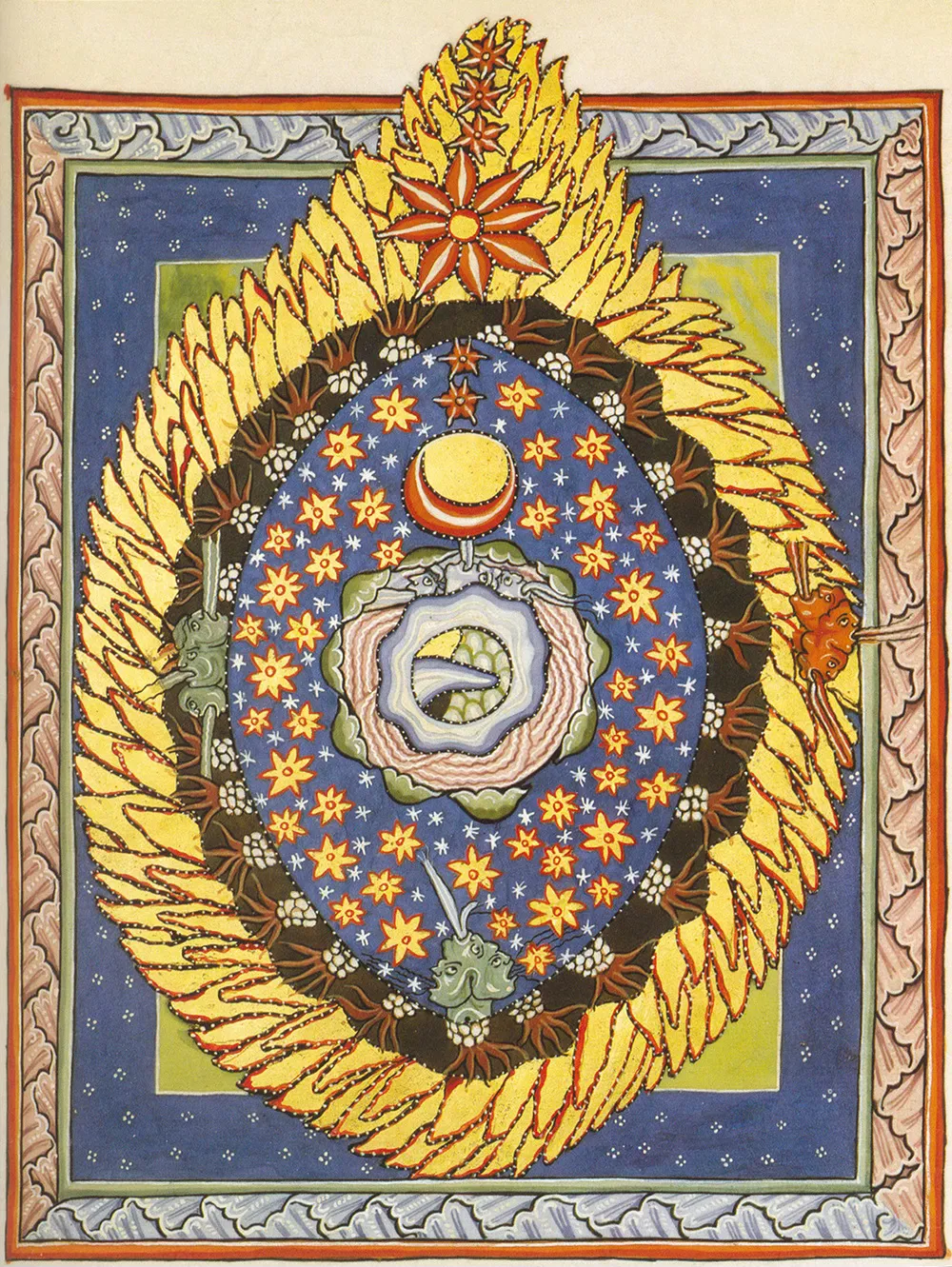

Scintillating scotomas

It’s weird to think that I was about my son’s age (17) when I started getting migraines. It wasn’t a massive surprise: there were migraineurs on both sides of my family, including my mother and my paternal grandmother. I may have literally dodged a bullet: being susceptible to migraines disqualifies you from pretty much every role in the Royal Air Force, to which I was in the process of applying.

These days, partly through stress management, ensuring I get good sleep, avoiding dehyrdration, and taking some supplements I’ve found helpful, my migraines are both less frequent and less extreme. They’re still part of who am, though, and I know to get off screens immediately and take some of my meds if my vision starts getting distorted.

How to describe a scintillating scotoma? It’s one of the most common symptoms of a migraine, but unless you’ve had one, it sounds unreal. A scintillating scotoma is like a barbed ripple in the pool of sight. It’s a skeletal Magic Eye raised up from the flatness of the world. It’s a glare on the tarmac as you drive West at sunset on a rain-slick freeway—only when you turn your head, it’s still there, so you have to pull over, close your eyes, and wait out the slow-motion firework working its way across your brain.

[…]

In the absence of an organizing mind, everything comes unglued. Faces go missing and dark holes seem to eat half the universe. Migraine sufferers can experience the uncanny sense of consciousness doubling known as déja-vu, or its cousin, jamais-vu, in which the world feels newly-made. The world might feel suddenly very unreal, fracture into a mosaic, or slow to a stop-motion pace, dropping frames. The self might cleave in two in a fit of somatopsychic duality. Writing about these bizarre and horrifying perceptual phenomena, the late Oliver Sacks observed that migraines “show us how the brain-mind constructs ‘space’ and ‘time,’ by demonstrating what happens when space and time are broken, or unmade.”

[…]

According to Migraine Art: The Migraine Experience From Within, migraine auras are as old as humankind—so old, perhaps, that they may have inspired the geometric forms of Stone Age cave drawings. Which makes recent attempts to generate migraine auras using convolutional neural networks seem particularly poignant to me: what began in stone, animated by the hot flicker of firelight, continues 5,000 years later, deep in the heart of servers whose mineral components were mined from the same dark Earth.

Source: Wild Information

Image: Manuscript illumination by Hildegard of Bingen, 1511 (who was a migraineur)

Career vs Job

This post by Tim Klapdor is definitely related the Aeon article I quoted about carving out time for reflection.

People are surprised when I say that I do about 20-25 hours of paid work per week. Somehow that’s ‘part time’. But I live a full life: studying, writing, taking my kids here, there, and everywhere. The only thing missing? I’d like to travel more, professionally.

A career contains a multitude of jobs. Some of them are the ones you get paid for, but many of them aren’t. And that’s often where the confusion comes into play. The paid job begins to bleed into other areas, and you associate the paid job with all the other jobs. They get lumped together as a career, but they are distinct and need to be kept separate. It’s our mind that blends them together, so every so often, we need to pull focus, reevaluate and paint in the edges to make it clear what our jobs really are.

[…]

In reflection, I can say that for the last few years, I’ve paid too much attention to my paid job and not my career. I’ve allowed the job to expand beyond its parameters and edges to consume everything around it—my time, attention, and priorities. What I need to do, and what I plan to do in 2024, is to switch that.

I want to focus on my career, not my job.

Source: Tim Klapdor

Absence is not a defect(ion)

I hadn’t thought of the early days of the pandemic as being akin to a general labour strike. Interesting. I could quote the entirety of this article, but I’ll just mention one thing that I haven’t included below: “It is because of its emptiness that the room is useful.” (Lao Tzu). The author of this article, David J Siegel, uses this to make the point that I’ve used as the title for this post; that absence is not defection.

The early period of the pandemic (which approximated in many respects a kind of general labour strike) gave some of us an intimation of what life lived largely off the clock can be like when much of what passes for work is suspended or slowed and we are afforded precious ‘little gaps of solitude and silence’, as the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze called them, to engage in worthy pursuits that elude us under normal circumstances. We found incomparable personal freedoms and new opportunities for enrichment and fulfilment in the cessation of many of our standard operating procedures.

Then, as everyone recalls, we were summoned back to the office. But, once we had experienced this new way of being, the prospect of returning to the old order – submitting to the control, policing and surveillance of our former workaday lives – became almost unthinkable, especially for members of a chronically insecure workforce forced to endure low pay, lack of opportunity for advancement, inflexible schedules, and a multitude of everyday insults and indignities. Perhaps the chief insult to us all is the governing assumption that we must be collocated – or collated – to do our best work, despite having demonstrated our capacity for self-directed productivity from home (or other private quarters) under the most trying circumstances.

[…]

In The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering (2009), Byung-Chul Han suggests that our experience of intervals is being ‘destroyed in order to produce total proximity and simultaneity’. When everything (and everyone) is within reach at all times, we lose a sense of what it means to be in – and even to savour – transitional states of in-betweenness. As an antidote, [some authors] recommend that we ‘tarry with time’ and ‘make spaces for the play of purposeless action’.

We can, in other words, reappropriate some of the time and space being withdrawn from us. These can be reclaimed in the fugitive moments we thieve from the calendar, or they can be recovered in what the anarchist Hakim Bey in 1985 called ‘temporary autonomous zones’: undetectable underground enclaves that we carve out of the landscape of our everyday lives in order to find or free ourselves. Simultaneously, practices of disengagement might withdraw from organisations (workplaces primary among them) their extraordinary power to mediate – to dictate and direct – far too many aspects of our existence and experience. Opting to bypass certain workplace amenities and conveniences expertly designed to keep us at work – the cafeteria, the fitness centre, the dry cleaner, the onsite health clinic – might not seem like much of a tactic of rebellion, but it does its part to lessen our dependence on our employer as lifehack, helpmate or healer.

[…]

Withdrawal has an almost universally negative connotation in public life, where it is treated as the ultimate transgression and disdained as retreat or defeat – the very opposite of engagement. However, to withdraw is also, crucially, to repair – both to go to a place and to mend. From this perspective, withdrawal is not merely a defeatist tack; rather, it is, or can be, direct action for a restoration of intellectual life – the kind that is free to ask (to fully engage with) impertinent questions – in settings that have practically banished it, made it inaccessible, or are attempting to monitor and monetise it according to terms not of our choosing.

[…]

Among the questions some of us are investigating in our contemplative moments of disengagement, withdrawal, removal, retreat or escape – however we choose to designate those instances when we take our leave – are these: when, or to what extent, do our norms of organisational affiliation and attachment make us sick or otherwise compound the very problems such forms of connection are meant to solve? In what ways might our occasional absences improve our solitary and even our solidary experiences of work and of life more generally?

Source: Aeon

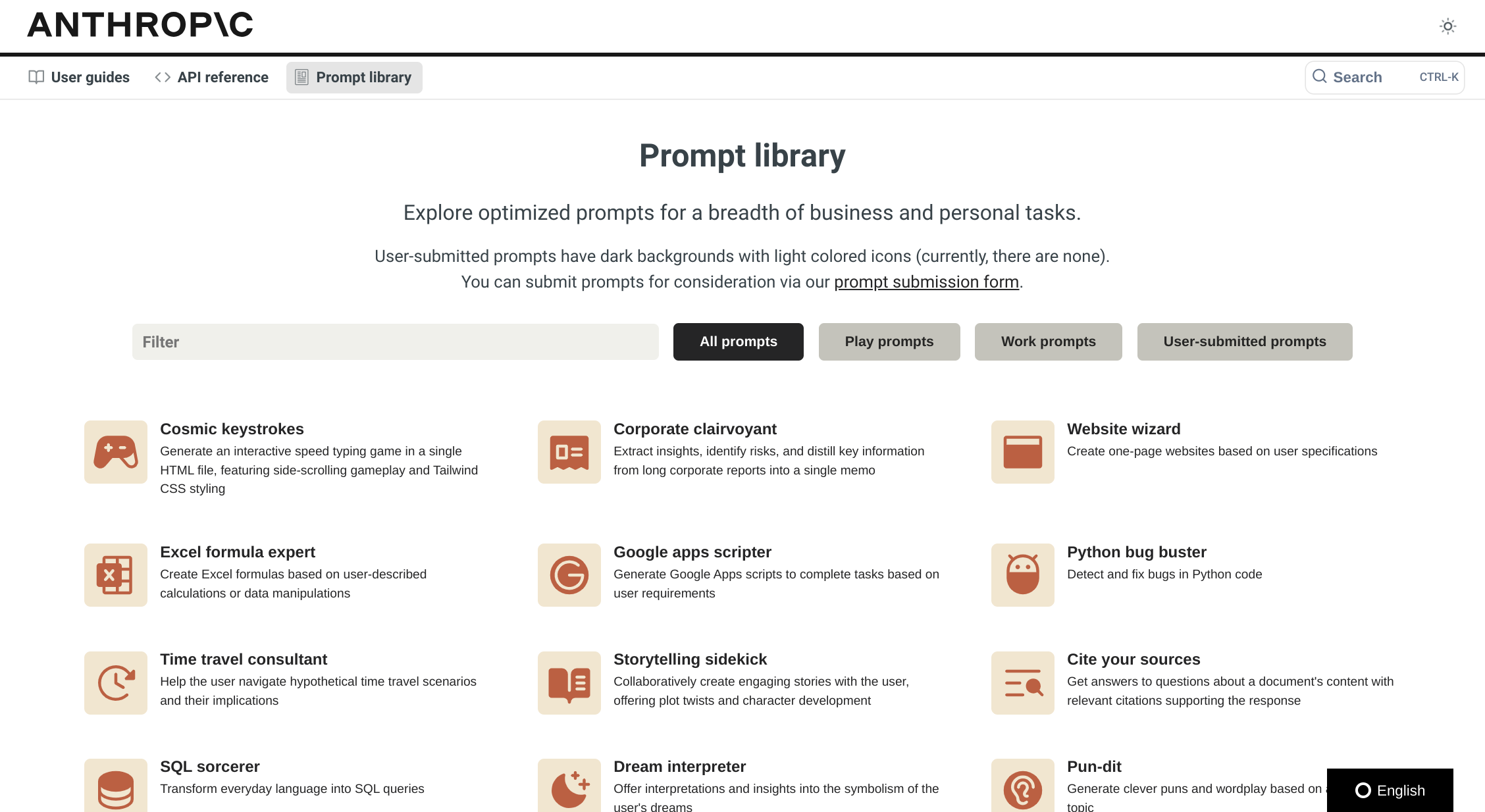

Claude's Prompt Library

Anthropic, the organisation set up by ex-OpenAI staffers, has recently released Claude 3. This is apparently even more powerful than GPT-4, although I haven’t had a chance to play with it yet.

Alongside the release, Anthropic has also shared a Prompt Library which, I guess, is the equivalent of OpenAI’s GPTs.

Source: Anthropic Prompt Library

Sports betting and neoliberal atomisation

The only times I’ve ever betted on sports is with my father. Back when I lived at home, we’d all choose a horse in the Grand National (out of a hat) and I’d go down with him to the bookies to put the bets on. And then, when we went to a football match at Sunderland, we’d decide what bet to put on, too.

I’ve never betted on sports by myself. It’s a slippery slope, as I know what I’m like. When I was my son’s age (17) I was mildly addicted to scratchcards for a few weeks, but quit when I won enough to break even. That’s why the whole world of sports betting, which I know must be huge given that almost every Premier League football team is sponsored by a related company, is a black box to me.

Drew Austin talks about sports betting not only being the further atomisation of an activity which was at least nominally social, but also the way that it reduces a complex bundle of qualitative emotions down to a set of flat, quantitative, numbers.

As the Facebook/Google/Twitter clearnet dissolves and the internet becomes a dark forest, another relatively recent tech category offers a lens for anticipating the future of shared experience and solipsism: sports betting apps. Although largely unleashed by regulatory changes rather than technical innovation, the rise of mainstream, app-enabled sports gambling has reframed a still-powerful bulwark of mass culture as a solitary pursuit. As televised sports continue fragmenting into digital content just like everything else, sports betting creates a derivative market on top of that content, which in turn yields its own additional bounty of content. If you’ve ever bet on a game and then watched it with other people, you probably realized quickly that nobody cares about your betting angle(s) and that you have to shut up about it. You’re on your own. But if you show up at the Super Bowl party wearing a Kansas City Chiefs jersey, you are a legible entity, and everyone has something to talk to you about. To bet on sports is to share the same space (literal or figurative) with a multitude of people who have their own specific angle and only the meta-game in common. Sports gambling is even more fascinating, however, in the way it alters your brain as a spectator of the game: You exchange a complex bundle of emotional and aesthetic nuance for a purely quantitative perspective, which highlights everything that benefits you and pushes the rest to the background. It’s how it would feel to be a computer watching sports. A lot of things we do on the internet feel like that. Who needs NPCs to interact with when we all act like them anyway? We pay so much attention to how computers are learning to be human, but forget we’re also learning to act like them.

Source: Kneeling Bus

Image: DALL-E 3

Subject, Consumer, Citizen

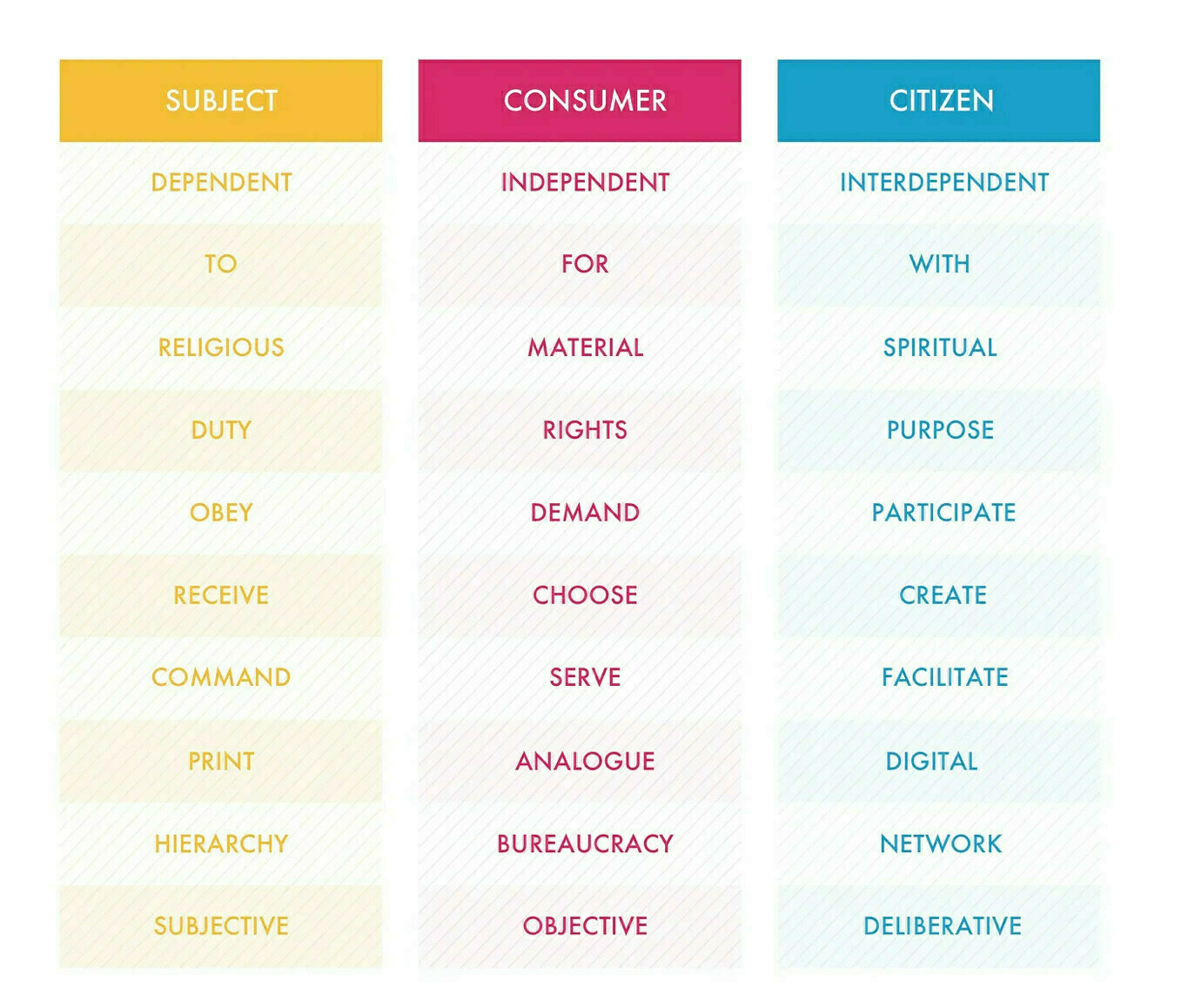

Andrew Curry reflects on the work of Jon Alexander, author of a book called Citizens (2022). Alexander has been on a bit of a journey talking to people, and has made some discoveries.

I’m mainly sharing this for the diagram, which Stowe Boyd also picked up on, and provides a better commentary than I ever could. All I’ll say is that it’s good to see things laid out so clearly, although I would have put the ‘Subject’ column to the right (where it is politically) and made it an easier-to read colour!

[H]eaven knows we have a lot of Sensible Grown-Up Politicians around the place. Albanese in Australia, Starmer in the UK. But: because they have not yet realised, or acknowledged, that our political systems are failing, they don’t have the tools to deal with authoritarianism.

But it’s not just down to them. We can’t sit down in Restaurant Hope and wait for the menu. We need to be in the kitchen. […]

Authoritarians offer to replace this with a story about being a subject: if we put them in power, they will fix things for us (although they don’t, of course).

[…]

We need to believe in people if we, the people, are to have any hope for ourselves and for humanity.

Source: Just Two Things

A truly liberatory (digital) future for everyone

After giving a potted history of the internet and all of the ways it has failed to live up to its promise, Paris Marx suggests that we need to start over with the entire tech industry. It’s hard to disagree.

My internet habits are vastly different to what they were a decade ago. Back then, I was seven years into using Twitter, had a great following and ‘personal learning network’. The world, pre-Brexit and Trump had the seeds of the turmoil to come, but Big Tech was nowhere near as brazen as it is post-pandemic, and coked-up on AI fever dreams.

There can only be only conclusion from all of this: the digital revolution has failed. The initial promise was a deception to lay the foundation for another corporate value-creation scheme, but the benefits that emerged from it have been so deeply eroded by commercial imperatives that the drawbacks far outweigh the remaining redeeming qualities — and that only gets worse with every day generative AI tools are allowed to keep flooding the web with synthetic material.

The time for tinkering around the edges has passed, and like a phoenix rising from the ashes, the only hope to be found today is in seeking to tear down the edifice the tech industry has erected and to build new foundations for a different kind of internet that isn’t poisoned by the requirement to produce obscene and ever-increasing profits to fill the overflowing coffers of a narrow segment of the population.

There were many networks before the internet, and there can be new networks that follow it. We don’t have to be locked into the digital dystopia Silicon Valley has created in a network where there was once so much hope for something else entirely. The ongoing erosion already seems to be sending people fleeing by ditching smartphones (or at least trying to reduce how much they use them), pulling back from the mess that social media has become, and ditching the algorithmic soup of streaming services.

Personal rejection is a welcome development, but as the web declines, we need to consider what a better alternative could look like and the political project it would fit within. We also can’t fall for any attempt to cast a libertarian “declaration of independence” as a truly liberatory future for everyone.

Source: Disconnect

Image: DALL-E 3

Moderation is up to us now

I’ve curated my comfy middle-class life to such a degree that I mostly hear about the dark underbelly of the web / toxic online behaviour through publications such as Ryan Broderick’s excellent Garbage Day.

In his latest missive, Broderick gives the example of a comedian I’ve never encountered before by the name of Shane Gillis. Go and read the whole thing for the bigger context, but the main point Broderick is making I’ve bolded below. I would point out that the Fediverse is, in my experience, on the whole well-moderated. At least, better moderated than centralised social networks such as X and Instagram.

Last year, Gillis was a guest on the unwatchable “comedy “podcast” Flagrant and had to tell the hosts to stop pulling up and laughing at videos of people with Down Syndrome dancing. Clips from the episode recently started making the rounds again this week on Reddit and X. It’s incredibly uncomfortable to watch.

And, sure, Gillis is not directly organizing any of this larger edgelord behavior. But he can’t be separated from it either. As I wrote above, the companies that run the internet have all but given up moderating it, so that work has to be done by us now. We have to manage our own communities and we have to look out for the most vulnerable. People with Down Syndrome and their loved ones should be able to openly share their lives online without worrying about getting turned into a meme or converted into engagement bait by some anonymous goblin. Even if that means dropping your chill bro facade and riling up the Stoolies when you tell people to stop.

Gills has the biggest podcast on Patreon. He’s been at the top of their charts for over a year. He has a massive platform and he built it by letting every awful guy in the country project themselves on to him. And while he does genuinely seem to really want to use that fame to bring visibility to the Down Syndrome community — and I think it’s admirable that he does — he’s not willing to draw a clear line between visibility and exploitation.

Source: Garbage Day

Image: DALL-E 3

Hope vs Natality

Trigger warnings: death, persecution, suicide

Over on my personal blog I wrote that, given the depth of the climate emergency,‘hope’ is the wrong thing to be focusing upon. Will Richardson left a comment which pointed me towards this article by Samantha Rose Hill, a biographer of Hannah Arendt, for Aeon.

Arendt was a German-American historian and philosopher who escaped the Nazis. This article is about Arendt’s rejection in her work of the concept of ‘hope’ as being a lot less useful than action. Before getting to Arendt’s thoughts, I just want to share this quotation that is included in the article from Tadeusz Borowski, a Polish poet who wrote about the ways in which hope was used to destroy Jewish humanity. Borowski wrote the following lines while reflecting on his imprisonment in Auschwitz. He killed himself soon afterwards:

Never before in the history of mankind has hope been stronger than man, but never also has it done so much harm as it has in this war, in this concentration camp. We were never taught how to give up hope, and this is why today we perish in gas chambers.

Arendt suggests that hope is part of a desire for a happy ending, not based on the facts around us, but rather wishful thinking:

Many discussions of hope veer toward the saccharine, and speak to a desire for catharsis. Even the most jaded observers of world affairs can find it difficult not to catch their breath at the moment of suspense, hoping for good to triumph over evil and deliver a happy ending. For some, discussions of hope are attached to notions of a radical political vision for the future, while for others hope is a political slogan used to motivate the masses. Some people uphold hope as a form of liberal faith in progress, while for others still hope expresses faith in God and life after death.

Arendt breaks with these narratives. Throughout much of her work, she argues that hope is a dangerous barrier to acting courageously in dark times. She rejects notions of progress, she is despairing of representative democracy, and she is not confident that freedom can be saved in the modern world. She does not even believe in the soul, as she writes in one love letter to her husband. The political theorist George Kateb once remarked that her work is ‘offensive to a democratic soul’. When she was awarded an honorary degree at Smith College in Massachusetts in 1966, the president said: ‘Your writings challenge the mind, disturb the conscience, and depress the spirit of your readers; yet out of your wisdom and firm belief in mankind’s inner strength comes a sure hope.’

I’ve been listening to Ep.28 (‘Superhumanly Inhuman’) of Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History: Addendum which is about the Holocaust. It’s absolutely awful listening, but important stuff to know about. The article continues by talking about this dark period for Jewish and world history:

It was holding on to hope, Arendt argued, that rendered so many helpless. It was hope that destroyed humanity by turning people away from the world in front of them. It was hope that prevented people from acting courageously in dark times.

Caught between fear and ‘feverish hope’, the inmates in the ghetto were paralysed. The truth of ‘resettlement’ and the world’s silence led to a kind of fatalism. Only when they gave up hope and let go of fear, Arendt argues, did they realise that ‘armed resistance was the only moral and political way out’.

Instead, Arendt coined a new term: natality which celebrates the miracle of birth and continued human existence:

An uncommon word, and certainly more feminine and clunkier-sounding than hope, natality possesses the ability to save humanity. Whereas hope is a passive desire for some future outcome, the faculty of action is ontologically rooted in the fact of natality. Breaking with the tradition of Western political thought, which centred death and mortality from Plato’s Republic through to Heidegger’s Being and Time (1927), Arendt turns towards new beginnings, not to make any metaphysical argument about the nature of being, but in order to save the principle of humanity itself. Natality is the condition for continued human existence, it is the miracle of birth, it is the new beginning inherent in each birth that makes action possible, it is spontaneous and it is unpredictable. Natality means we always have the ability to break with the current situation and begin something new. But what that is cannot be said.

Hill, the author of the Aeon article, argues that:

Conceptually, natality can be understood as the flipside of hope:

What I love about this approach is that, as the article says, it’s kind of a “secular article of faith,” placing the responsibility for action firmly in our hands. Hope is, to some degree, the wish to be told soothing stories by a authoritative figure. It’s time for us to grow up.

Source: Aeon

Image: DALL-E 3