2019

- Platform avoidance,

- Infrastructural avoidance

- Hardware experiments

- Digital homesteading

- It reminds you to act

- It motivates you to continue

- It provides immediate satisfaction

Through the looking-glass

Earlier this month, George Dyson, historian of technology and author of books including Darwin Among the Machines, published an article at Edge.org.

In it, he cites Childhood’s End, a story by Arthur C. Clarke in which benevolent overlords arrive on earth. “It does not end well”, he says. There’s lots of scaremongering in the world at the moment and, indeed, some people have said for a few years now that software is eating the world.

Dyson comments:

The genius — sometimes deliberate, sometimes accidental — of the enterprises now on such a steep ascent is that they have found their way through the looking-glass and emerged as something else. Their models are no longer models. The search engine is no longer a model of human knowledge, it is human knowledge. What began as a mapping of human meaning now defines human meaning, and has begun to control, rather than simply catalog or index, human thought. No one is at the controls. If enough drivers subscribe to a real-time map, traffic is controlled, with no central model except the traffic itself. The successful social network is no longer a model of the social graph, it is the social graph. This is why it is a winner-take-all game. Governments, with an allegiance to antiquated models and control systems, are being left behind.

I think that’s an insightful point: human knowledge is seen to be that indexed by Google, friendships are mediated by Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and to some extent what possible/desirable/interesting is dictated to us rather than originating from us.

We imagine that individuals, or individual algorithms, are still behind the curtain somewhere, in control. We are fooling ourselves. The new gatekeepers, by controlling the flow of information, rule a growing sector of the world.What deserves our full attention is not the success of a few companies that have harnessed the powers of hybrid analog/digital computing, but what is happening as these powers escape into the wild and consume the rest of the world

Indeed. We need to raise our sights a little here and start asking governments to use their dwindling powers to break up mega corporations before Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook are too powerful to stop. However, given how enmeshed they are in everyday life, I’m not sure at this point it’s reasonable to ask the general population to stop using their products and services.

Source: Edge.org

Surfacing popular Google Sheets to create simple web apps

I was struck by the huge potential impact of this idea from Marcel van Remmerden:

Here is a simple but efficient way to spot Enterprise Software ideas — just look at what Excel sheets are being circulated over emails inside any organization. Every single Excel sheet is a billion-dollar enterprise software business waiting to happen.I searched "google sheet" education and "google sheet" learning on Twitter just now and, within about 30 seconds found:

…and:

…and:

These are all examples of things that could (and perhaps should) be simple web apps.In the article, van Remmerden explains how he created a website based on someone else’s Google Sheet (with full attribution) and started generating revenue.

It’s a little-known fact outside the world of developers that Google Sheets can serve as a very simple database for web applications. So if you’ve got an awkward web-based spreadsheet that’s being used by lots of people in your organisation, maybe it’s time to productise it?

Source: Marcel van Remmerden

Federico Leggio's type animations

These type animations by Federico Leggio, a freelance graphic designer based in Sicily, are incredible:

Source: Federico Leggio (via Dense Discovery)

Volume of work

This definitely speaks to me:

Quantity has a quality all its own as Lenin said. The sheer volume of your work is what works as a signal of weirdness, because anyone can be do a one-off weird thing, but only volume can signal a consistently weird production sensibility that will inspire people betting on you. The energy evident in a body of work is the most honest signal about it that makes people trust you to do things for them.Source: Venkatesh Rao (via Tom Critchlow)

What did the web used to be like?

One of the things it’s easy to forget when you’ve been online for the last 20-plus years is that not everyone is in the same boat. Not only are there adults who never experienced the last millennium, but varying internet adoption rates mean that, for some people, centralised services like YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are synonymous with the web.

Stories are important. That’s why I appreciated this Hacker News thread with the perfect title and sub-title:

Ask HN: What was the Internet like before corporations got their hands on it? What was the Internet like in its purest form? Was it mainly information sharing, and if so, how reliable was the information?There's lots to unpack here: corporate takeover of online spaces, veracity of information provided, and what the 'purest form' of the internet actually is/was.

Inevitably, given the readership of Hacker News, the top-voted post is technical (and slightly boastful):

1990. Not very many people had even heard of it. Some of us who'd gotten tired of wardialing and Telenet/Tymnet might have had friends in local universities who clued us in with our first hacked accounts, usually accessed by first dialing into university DECServers or X.25 networks. Overseas links from NSFNet could be as slow as 128kbit and you were encouraged to curtail your anonymous FTP use accordingly. Yes you could chat and play MUDs, but you could also hack so many different things. And admins were often relatively cool as long as you didn't use their machines as staging points to hack more things. If you got your hands on an outdial modem or x.25 gateway, you were sitting pretty sweet (until someone examined the bill and kicked you out). It really helped to be conversant in not just Unix, but also VMS, IBM VM/CMS, and maybe even Primenet. When Phrack came out, you immediately read it and removed it from your mail spool, not just because it was enormous, but because admins would see it and label you a troublemaker.I’ve already detailed my early computing history (up to 2009) for a project that asked for my input. I’ll not rehash it here, but the summary is that I got my first PC when I was 15 for Christmas 1995, and (because my parents wouldn’t let me) secretly started going online soon after.We knew what the future was, but it was largely a secret. We learned Unix from library books and honed skills on hacked accounts, without any ethical issue because we honestly felt we were preparing ourselves and others for a future where this kind of thing should be available to everyone.

We just didn’t foresee it being wirelessly available at McDonalds, for free. That part still surprises me.

My memory of this from an information-sharing point of view was that you had to be very careful about what you read. Because the web was smaller, and it was only the people who were really interested in getting their stuff out there who had websites, there was a lot of crazy conspiracy theories. I’m kind of glad that I went on as a reasonably-mature teenager rather than a tween.

Although I’ve very happy to be able to make my living primarily online, I suppose I feel a bit like this commenter:

This will probably come across as Get Of My Lawn type of comment. What I remember most about internet pre Facebook in particular and maybe Pre-smart phones. It was mostly a place for geeks. Geeks wrote blogs or had personal websites. Non geek stuff was more limited. It felt like a place where the geeks that were semi socially outcast kind of ran the place.Another commenter pointed to a short blog post he wrote on the subject, where he talks about how things were better when everyone was anonymous:Today the internet feels like the real world where the popular people in the real world are the most popular people online. Where all the things that I felt like I escaped from on the net before I can no longer avoid.

I’m not saying that’s bad. I think it’s awesome that my non tech friends and family can connect and or share their lives and thoughts easily where as before there was a barrier to entry. I’m only pointing out that, at least for me, it changed. It was a place I liked or felt connected to or something, maybe like I was “in the know” or I can’t put my finger on it. To now where I have no such feelings.

Maybe it’s the same feeling as liking something before it’s popular and it loses that feeling of specialness once everyone else is into it. (which is probably a bad feeling to begin with)

When it was anonymous, your name wasn’t attached to everything you did online. Everyone went by a handle. This means you could start a Geocities site and carve out your own niche space online, people could befriend and follow you who normally wouldn’t, and even the strangest of us found a home. All sorts of whacky, impossible things were possible because we weren’t bound by societal norms that plague our daily existence.I get that, but I think that things that make sense and are sustainable for the few, aren't necessarily so for the many. There's nothing wrong with nostalgia and telling stories about how things used to be, but as someone who used to teach the American West, there is (for better or worse) a parallel there with the evolution of the web.

The closest place to how the web was that I currently experience is Mastodon. It’s fully of geeks, marginalised groups, and weird/wacky ideas. You’d love it.

Source: Hacker News

Old web screenshot compilation image via Vice

Hong Kong shutter art

After never having visited Barcelona before November 2017, in the subsequent 12 months following, I went there five times. One of the things that struck me was the art in the city; some municipal, some architectural, and some more vernacular (i.e. graffiti-based).

When I was in Denver a few months ago, Noah Geisel was kind enough to give me a walking tour of some of the (partly commissioned) street art there. It was incredible.

I’ve never been to Hong Kong, and am unlike to go there any time soon, but this Twitter thread of Hong Kong shutter art makes me want to!

Source: Hong Kong Hermit

True test of intelligence (quote)

"The true test of intelligence is not how much we know how to do, but how to behave when we don’t know what to do."

(John Holt)Hierarchies and large organisations

This 2008 post by Paul Graham, re-shared on Hacker News last week, struck a chord:

What's so unnatural about working for a big company? The root of the problem is that humans weren't meant to work in such large groups.I really enjoyed working at the Mozilla Foundation when it was around 25 people. By the time it got to 60? Not so much. It’s potentially different with every organisation, though, and how teams are set up.Another thing you notice when you see animals in the wild is that each species thrives in groups of a certain size. A herd of impalas might have 100 adults; baboons maybe 20; lions rarely 10. Humans also seem designed to work in groups, and what I’ve read about hunter-gatherers accords with research on organizations and my own experience to suggest roughly what the ideal size is: groups of 8 work well; by 20 they’re getting hard to manage; and a group of 50 is really unwieldy.

Graham goes on to talk about how, in large organisations, people are split into teams and put into a hierarchy. That means that groups of people are represented at a higher level by their boss:

A group of 10 people within a large organization is a kind of fake tribe. The number of people you interact with is about right. But something is missing: individual initiative. Tribes of hunter-gatherers have much more freedom. The leaders have a little more power than other members of the tribe, but they don't generally tell them what to do and when the way a boss can.These words may come back to haunt me, but I have no desire to work in a huge organisation. I’ve seen what it does to people — and Graham seems to agree:[…]

[W]orking in a group of 10 people within a large organization feels both right and wrong at the same time. On the surface it feels like the kind of group you’re meant to work in, but something major is missing. A job at a big company is like high fructose corn syrup: it has some of the qualities of things you’re meant to like, but is disastrously lacking in others.

The people who come to us from big companies often seem kind of conservative. It's hard to say how much is because big companies made them that way, and how much is the natural conservatism that made them work for the big companies in the first place. But certainly a large part of it is learned. I know because I've seen it burn off.Perhaps there's a happy medium? A four-day workweek gives scope to either work on a 'side hustle', volunteer, or do something that makes you happier. Maybe that's the way forward.

Source: Paul Graham

Exit option democracy

This week saw the launch of a new book by Shoshana Zuboff entitled The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. It was featured in two of my favourite newspapers, The Observer and the The New York Times, and is the kind of book I would have lapped up this time last year.

In 2019, though, I’m being a bit more pragmatic, taking heed of Stoic advice to focus on the things that you can change. Chiefly, that’s your own perceptions about the world. I can’t change the fact that, despite the Snowden revelations and everything that has come afterwards, most people don’t care one bit that they’re trading privacy for convenience..

That puts those who care about privacy in a bit of a predicament. You can use the most privacy-respecting email service in the world, but as soon as you communicate with someone using Gmail, then Google has got the entire conversation. Chances are, the organisation you work for has ‘gone Google’ too.

Then there’s Facebook shadow profiles. You don’t even have to have an account on that platform for the company behind it to know all about you. Same goes with companies knowing who’s in your friendship group if your friends upload their contacts to WhatsApp. It makes no difference if you use ridiculous third-party gadgets or not.

In short, if you want to live in modern society, your privacy depends on your family and friends. Of course you have the option to choose not to participate in certain platforms (I don’t use Facebook products) but that comes at a significant cost. It’s the digital equivalent of Thoreau taking himself off to Walden pond.

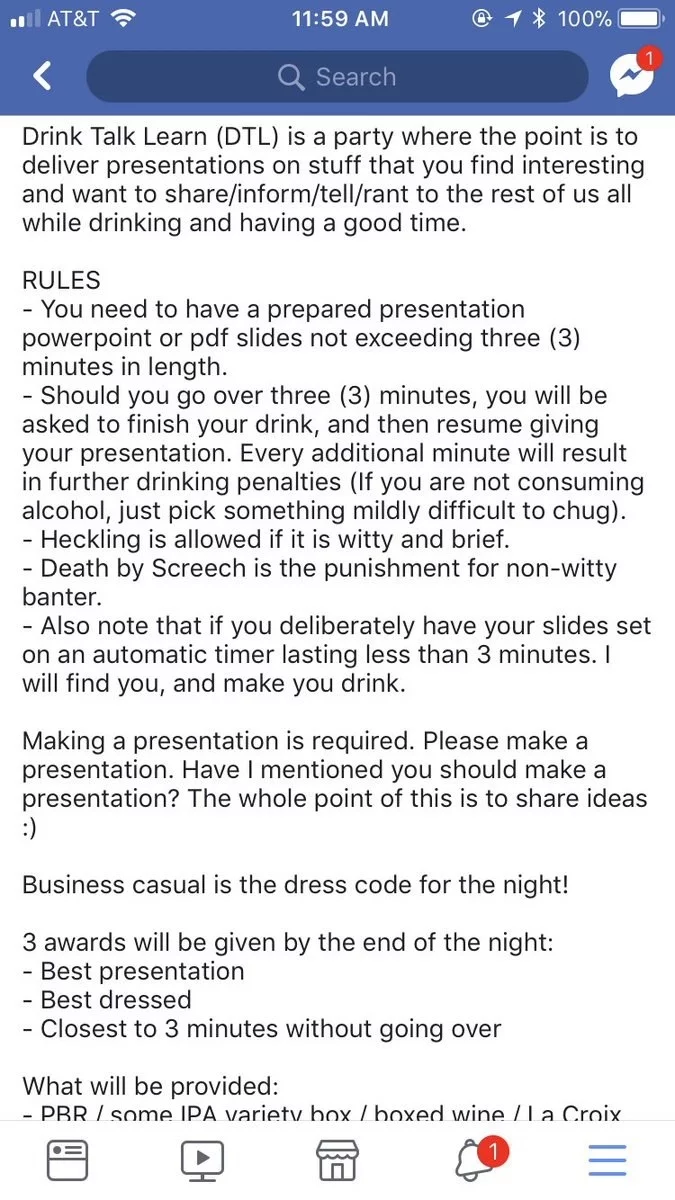

In a post from last month that I stumbled across this weekend, Nate Matias reflects on a talk he attended by Janet Vertesi at Princeton University’s Center for Information Technology Policy. Vertesi, says Matias, tried four different ways of opting out of technology companies gathering data on her:

The basic assumption of markets is that people have choices. This idea that “you can just vote with your feet” is called an “exit option democracy” in organizational sociology (Weeks, 2004). Opt-out democracy is not really much of a democracy, says Janet. She should know–she’s been opting out of tech products for years.The option Vertesi advocates for going Google-free is a pain in the backside. I know, because I've tried it:

To prevent Google from accessing her data, Janet practices “data balkanization,” spreading her traces across multiple systems. She’s used DuckDuckGo, sandstorm.io, ResilioSync, and youtube-dl to access key services. She’s used other services occasionally and non-exclusively, and varied it with open source alternatives like etherpad and open street map. It’s also important to pay attention to who is talking to whom and sharing data with whom. Data balkanization relies on knowing what companies hate each other and who’s about to get in bed with whom.The time I've spent doing these things was time I was not being productive, nor was it time I was spending with my wife and kids. It's easy to roll your eyes at people "trading privacy for convenience" but it all adds up.

Talking of family, straying too far from societal norms has, for better or worse, negative consequences. Just as Linux users were targeted for surveillance, so Vertisi and her husband were suspected of fraud for browsing the web using Tor and using cash for transactions:

Trying to de-link your identity from data storage has consequences. For example, when Janet and her husband tried to use cash for their purchases, they faced risks of being reported to the authorities for fraud, even though their actions were legal.And then, of course, there's the tinfoil hat options:

...Janet used parts from electronics kits to make her own 2g phone. After making the phone Janet quickly realized even a privacy-protecting phone can’t connect to the network without identifying the user to companies through the network itself.I'm rolling my eyes at this point. The farthest I've gone down this route is use the now-defunct Firefox OS and LineageOS for microG. Although both had their upsides, they were too annoying to use for extended periods of time.

Finally, Vertesi goes down the route of trying to own all your own data. I’ll just point out that there’s a reason those of us who had huge CD and MP3 collections switched to Spotify. Looking after any collection takes time and effort. It’s also a lot more cost effective for someone like me to ‘rent’ my music instead of own it. The same goes for Netflix.

What I do accept, though, is that Vertesi’s findings show that ‘exit democracy’ isn’t really an option here, so the world of technology isn’t really democratic. My takeaway from all this, and the reason for my pragmatic approach this year, is that it’s up to governments to do something about all this.

Western society teaches us that empowered individuals can change the world. But if you take a closer look, whether it’s surveillance capitalism or climate change, it’s legislation that’s going to make the biggest difference here. Just look at the shift that took place because of GDPR.

So whether or not I read Zuboff’s new book, I’m going to continue my pragmatic approach this year. Meanwhile, I’ll continue to mute the microphone on the smart speakers in our house when they’re not being used, block trackers on my Android smartphone, and continue my monthly donations to work of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Open Rights Group.

Source: J. Nathan Matias

Implicit leverage

Tyler Cowen at Marginal Revolution asks how well we understand the organisations we work with and for:

Most (not all) organizations have forms of leverage which are built in and which do not show up as debt on the balance sheet. Banks may have off-balance sheet risk through derivatives, companies may sell off their valuable assets, and NBA teams may tank their ability to keep draft picks and free agents in their future.In other words, every organisation has people, other organisations, or resources on which it is dependent. That can look like event organisers not alienating a sponsor, universities maintaining their brand overseas so they can continue to recruit lucrative overseas students, and organisations doing well because of a handful of individuals that win investors' trust.

When it comes to politics, of course, ‘leverage’ is almost always something problematic. In fact, we usually use the phrase ‘in the pocket of’ instead to show our opprobrium when a politician has close financial ties to, say, a tobacco company or big business.

In other words, understanding how leverage works in everyday life, business, and politics is probably something we should be teaching in schools.

Source: Marginal Revolution

Image by Mike Cohen used under a Creative Commons License

Blockchain is about trust minimisation

I’ve always laughed when people talk about ‘trust’ and blockchain. Sometimes I honestly question whether blockchain boosters live in the same world as I do; the ‘trust’ they keep on talking about is a feature of life as it currently is, not in a crypto-utopia.

Albert Wenger takes this up in an excellent recent post:

One way to tell that trust was involved in a relationship is when we discover that the person (or company, or technology) acted in a way that harmed us and benefited them. At that point we feel betrayed. This provides a useful distinction between the concepts of trust and reliance. We rely on a clock to tell time. When the clock breaks we will feel disappointed. But when we buy a clock from someone who tells us it is a working clock, we trust them and when it doesn’t work, we feel betrayed (thanks to philosopher Annette Baier for this distinction).As I keep saying, blockchain is a really boring technology. It's super-useful for backend systems, but that's pretty much it. All of the glamour and excitement has come from speculators trying to inflate a bubble, as has happened many times before.

Now some people have been saying that crypto is exciting because it has “trust built in.” I, however, prefer a different formulation, which is that crypto systems are “trust minimized.”Exactly. What blockchain is useful for is when you have reason to mistrust the person you're dealing with. Instead of a complex network of trust based on blood ties, friendships, and alliances, we can now perform operations and transactions in a 'trust minimised' way.

We live in a world where large corporations (especially ones with scale or network effects) have often abused trust due to a misalignment of incentives driven by short-term oriented capital markets. There are different ways of tackling this problem, including new regulation, innovative forms of ownership and trust minimized crypto systems.So let's see blockchain for what it is: a breakthrough for international trading and compliance checking. I'm happy it exists but still, several years later, find it difficult to get too excited about. And I'll bet you all of your now-worthless Bitcoin that governments around the world will ensure that crypto-utopias turn into crypto-distopias.

Source: Continuations

Forging better habits

I’m very much looking forward to reading James Clear’s new book Atomic Habits. On his (very popular) blog, Clear shares a chapter in which he talks about the importance of using a ‘habit tracker’.

In that chapter, he states:

Habit formation is a long race. It often takes time for the desired results to appear. And while you are waiting for the long-term rewards of your efforts to accumulate, you need a reason to stick with it in the short-term. You need some immediate feedback that shows you are on the right path.At the start of the year I started re-using a very simple app called Loop Habit Tracker. It's Android-only and available via F-Droid and Google Play, and I'm sure there's similar apps for iOS.

You can see a screenshot of what I’m tracking at the top of this post. You simply enter what you want to track, how often you want to do it, and tick off when you’ve achieved it. Not only can the app prompt you, should you wish, but you can also check out your ‘streak’.

Clear lists three ways that a habit tracker can help:

If you’re struggling to make a new habit ‘stick’, I agree with Clear that doing something like this for six weeks is a particularly effective way to kickstart your new regime!

Source: James Clear

A reminder of how little we understand the world

"The important thing in science is not so much to obtain new facts as to discover new ways of thinking about them." (William Lawrence Bragg)Science is usually pointed to as a paradigm of cold, hard reason. But, as anyone who's ever studied the philosophy of science will attest, scientific theories — just like all human theories — are theory-laden.

This humorous xkcd cartoon is a great reminder of that.

Source: xkcd

The quixotic fools of imperialism

As an historian with an understanding of our country’s influence of the world over the last few hundred years, I look back at the British Empire with a sense of shame, not of pride.

But, even if you do flag-wave and talk about our nation’s glorious past, an article in yesterday’s New York Times shows how far we’ve falled:

The Brexiteers, pursuing a fantasy of imperial-era strength and self-sufficiency, have repeatedly revealed their hubris, mulishness and ineptitude over the past two years. Though originally a “Remainer,” Prime Minister Theresa May has matched their arrogant obduracy, imposing a patently unworkable timetable of two years on Brexit and laying down red lines that undermined negotiations with Brussels and doomed her deal to resoundingly bipartisan rejection this week in Parliament.I think I'd forgotten how useful the word mendacious is in this context ("lying, untruthful"):

When leaving countries after their imperialist adventures, members of the British ruling elite were fond of dividing countries with arbitrary lines. Cases in point: India, Ireland, the Middle East. That this doesn't work is blatantly obvious, and is a lazy way to deal with complex issues.From David Cameron, who recklessly gambled his country’s future on a referendum in order to isolate some whingers in his Conservative party, to the opportunistic Boris Johnson, who jumped on the Brexit bandwagon to secure the prime ministerial chair once warmed by his role model Winston Churchill, and the top-hatted, theatrically retro Jacob Rees-Mogg, whose fund management company has set up an office within the European Union even as he vehemently scorns it, the British political class has offered to the world an astounding spectacle of mendacious, intellectually limited hustlers.

It is a measure of English Brexiteers’ political acumen that they were initially oblivious to the volatile Irish question and contemptuous of the Scottish one. Ireland was cynically partitioned to ensure that Protestant settlers outnumber native Catholics in one part of the country. The division provoked decades of violence and consumed thousands of lives. It was partly healed in 1998, when a peace agreement removed the need for security checks along the British-imposed partition line.I'd love to think that we're nearing the end of what the Times calls 'chumocracy' and no longer have to suffer what Hannah Arendt called "the quixotic fools of imperialism". We can but hope.

Noise cancelling for cars is a no-brainer

We’re all familiar with noise cancelling headphones. I’ve got some that I use for transatlantic trips, and they’re great for minimising any repeating background noise.

Twenty years ago, when I was studying A-Level Physics, I was also building a new PC. I realised that, if I placed a microphone inside the computer case, and fed that into the audio input on the soundcard, I could use software to invert the sound wave and thus virtually eliminate fan noise. It worked a treat.

It doesn’t surprise me, therefore, to find that BOSE, best known for its headphones, are offering car manufacturers something similar with “road noise control”:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIzkgLdzd9g&w=560&h=315]

With accelerometers, multiple microphones, and algorithms, it’s much more complicated than what I rigged up in my bedroom as a teenager. But the principle remains the same.

Source: The Next Web

Going your own way (quote)

“To go wrong in one’s own way is better than to go right in someone else’s.”

(Fyodor Dostoevsky)

Location data in old tweets

What use are old tweets? Do you look back through them? If not, then they’re only useful to others, who are able to data mine you using a new toold:

The tool, called LPAuditor (short for Location Privacy Auditor), exploits what the researchers call an "invasive policy" Twitter deployed after it introduced the ability to tag tweets with a location in 2009. For years, users who chose to geotag tweets with any location, even something as geographically broad as “New York City,” also automatically gave their precise GPS coordinates. Users wouldn’t see the coordinates displayed on Twitter. Nor would their followers. But the GPS information would still be included in the tweet’s metadata and accessible through Twitter’s API.I deleted around 77,500 tweets in 2017 for exactly this kind of reason.

Source: WIRED

Remembering the past through photos

A few weeks ago, I bought a Google Assistant-powered smart display and put it in our kitchen in place of the DAB radio. It has the added bonus of cycling through all of my Google Photos, which stretch back as far as when my wife and I were married, 15 years ago.

This part of its functionality makes it, of course, just a cloud-powered digital photo frame. But I think it’s possible to underestimate the power that these things have. About an hour before composing this post, for example, my wife took a photo of a photo(!) that appeared on the display showing me on the beach with our two children when they were very small.

An article by Giuliana Mazzoni in The Conversation points out that our ability to whip out a smartphone at any given moment and take a photo changes our relationship to the past:

We use smart phones and new technologies as memory repositories. This is nothing new – humans have always used external devices as an aid when acquiring knowledge and remembering.Mazzoni points out that this can be problematic, as memory is important for learning. However, there may be a “silver lining”:[…]

Nowadays we tend to commit very little to memory – we entrust a huge amount to the cloud. Not only is it almost unheard of to recite poems, even the most personal events are generally recorded on our cellphones. Rather than remembering what we ate at someone’s wedding, we scroll back to look at all the images we took of the food.

Even if some studies claim that all this makes us more stupid, what happens is actually shifting skills from purely being able to remember to being able to manage the way we remember more efficiently. This is called metacognition, and it is an overarching skill that is also essential for students – for example when planning what and how to study. There is also substantial and reliable evidence that external memories, selfies included, can help individuals with memory impairments.She goes on to discuss the impact that viewing many photos from your past has on a malleable sense of self:But while photos can in some instances help people to remember, the quality of the memories may be limited. We may remember what something looked like more clearly, but this could be at the expense of other types of information. One study showed that while photos could help people remember what they saw during some event, they reduced their memory of what was said.

Research shows that we often create false memories about the past. We do this in order to maintain the identity that we want to have over time – and avoid conflicting narratives about who we are. So if you have always been rather soft and kind – but through some significant life experience decide you are tough – you may dig up memories of being aggressive in the past or even completely make them up.I'm not so sure that it's a good thing to tell yourself the wrong story about who you are. For example, although I grew up in, and identified with, a macho ex-mining town environment, I've become happier by realising that my identify is separate to that.

I suppose it’s a bit different for me, as most of the photos I’m looking at are of me with my children and/or my wife. However, I still have to tell myself a story of who I am as a husband and a father, so in many ways it’s the same.

All in all, I love the fact that we can take photos anywhere and at any time. We may need to evolve social norms around the most appropriate ways of capturing images in crowded situations, but that’s separate to the very great benefit which I believe they bring us.

Source: The Conversation

Acoustic mirrors

On the beach at Druridge Bay in Northumberland, near where I live, there are large blocks in various intervals. These hulking pieces of concrete, now half-submerged, were deployed on seafronts up and down England to prevent the enemy successfully landing tanks during the Second World War.

I was fascinated to find out that these aren’t the only concrete blocks that protected Britain. BBC News reports that ‘acoustic mirrors’ were installed for a very specific purpose:

More than 100 years ago acoustic mirrors along the coast of England were built with the intention of using them to detect the sound of approaching German zeppelins.Some of these, which vary in size, still exist, and have been photographed by Joe Pettet-Smith.The concave concrete structures were designed to pick up sound waves from enemy aircraft, making it possible to predict their flight trajectory, giving enough time for ground forces to be alerted to defend the towns and cities of Britain.

The reason most of us haven’t heard of them is that the technology improved so quickly. Pettet-Smith comments:

The sound mirror experiment, this idea of having a chain of concrete structures facing the Channel using sound to detect the flight trajectory of enemy aircraft, was just that - an experiment. They tried many different sizes and designs before the project was scrapped when radar was introduced.Fascinating. The historian (and technologist) within me loves this.The science was solid, but aircraft kept getting faster and quieter, which made them obsolete.

Source: BBC News